How Britain became super rich and a super power by selling even salt to Indians-BY STOPPING SALT PRODUCTION IN INDIA

m

m

- The Great Green Wall of Aravalli, a 1,600 km long and 5 km wide green ecological corridor of India

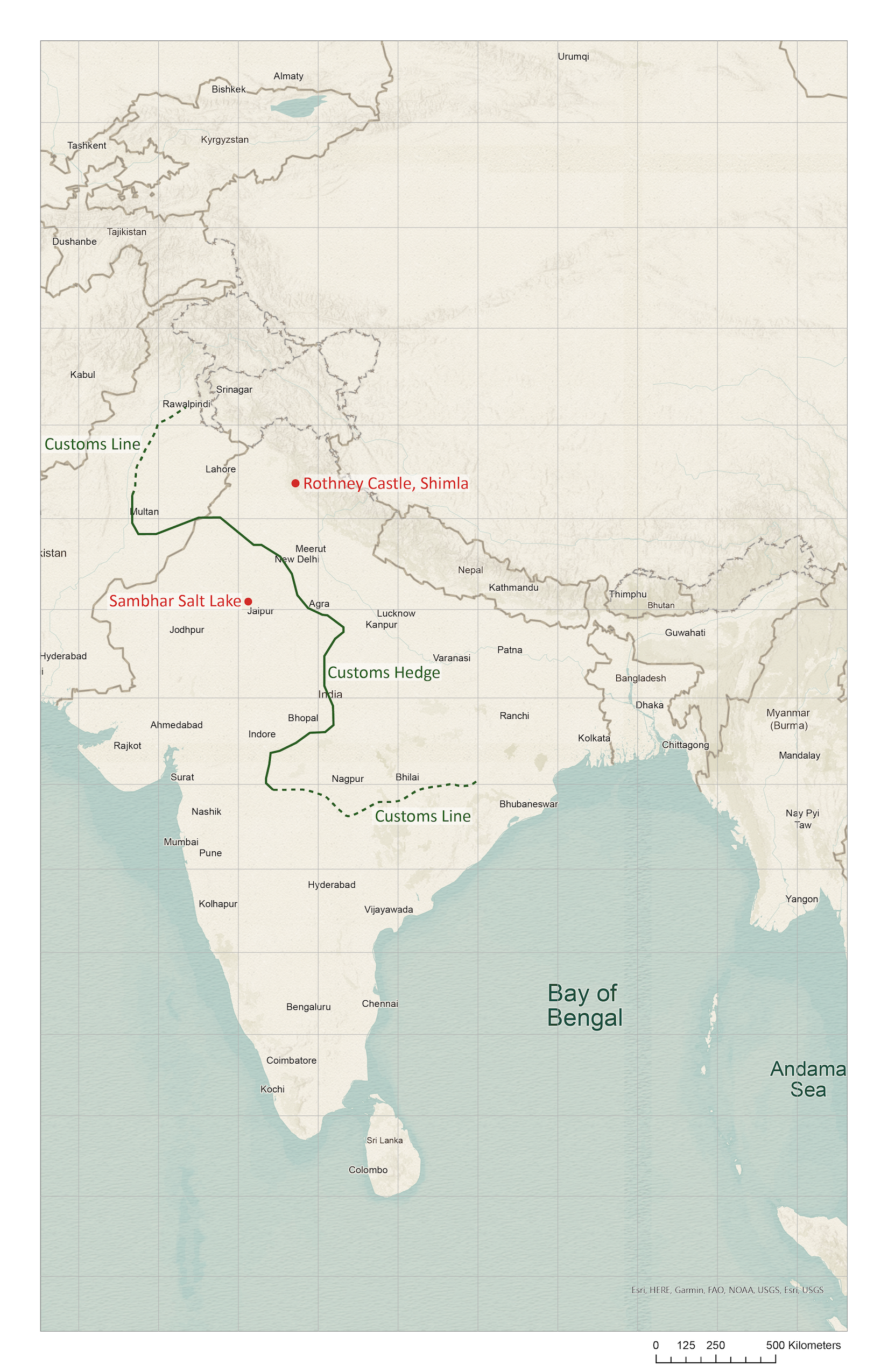

Inland Customs Line

The Inland Customs Line, incorporating the Great Hedge of India (or Indian Salt Hedge[1]), was a customs barrier built by the British colonial rulers of India to prevent smuggling of salt from coastal regions in order to avoid the substantial salt tax.

The customs line was begun under the East India Company and continued into direct British rule. The line had its beginnings in a series of customs houses established in Bengal in 1803 to prevent the smuggling of salt to avoid the tax. These customs houses were eventually formed into a continuous barrier that was brought under the control of the Inland Customs Department in 1843.

The line was gradually expanded as more territory was brought under British control until it covered more than 2,500 miles (4,000 km), often running alongside rivers and other natural barriers. It ran from the Punjab in the northwest to the princely states of Orissa, near the Bay of Bengal, in the southeast. The line was initially made of dead, thorny material such as the Indian plum but eventually evolved into a living hedge that grew up to 12 feet (3.7 m) high and was compared to the Great Wall of China. The Inland Customs Department employed customs officers, jemadars and men to patrol the line and apprehend smugglers, reaching a peak of more than 14,000 staff in 1872.

The line and hedge were abandoned in 1879 when the British seized control of the Sambhar Salt Lake in Rajasthan and applied tax at the point of manufacture. The salt tax itself remained in place until 1946.

Origins

When the Inland Customs Line was first conceived, British India was governed by the East India Company. This situation lasted until 1858 when the responsibility for government of the colony was transferred to the Crown following the events of the Indian Rebellion of 1857. By 1780 Warren Hastings, the company's Governor-General of India, had brought all salt manufacture in the Bengal Presidency under company control.[2] This allowed him to increase the ancient salt tax in Bengal from 0.3 rupees per maund (37 kg) to 3.25 rupees per maund by 1788, a rate that it remained at until 1879.[3] This brought in 6,257,470 rupees for the 1784–85 financial year, at a cost to an average Indian family of around two rupees per year (two months' income for a labourer).[4] There were taxes on salt in the other British India territories but the tax in Bengal was the highest, with the other taxes at less than a third of the Bengal tax rate.

It was possible to avoid paying the salt tax by extracting salt illegally in salt pans, stealing it from warehouses or smuggling salt from the princely states which remained outside of direct British rule. The latter was the greatest threat to the company's salt revenues.[5] Much of the smuggled salt came into Bengal from the west and the company decided to act to prevent this trade. In 1803 a series of customs houses and barriers were constructed across major roads and rivers in Bengal to collect the tax on traded salt as well as duties on tobacco and other imports.[6] These customs houses were backed up by "preventative customs houses" located near salt works and the coast in Bengal to collect the tax at source.[7]

These customs houses alone did little to prevent the mass avoidance of the salt tax. This was due to the lack of a continuous barrier, corruption within the customs staff and the westward expansion of Bengal towards salt-rich states.[7][8][9] In 1823 the Commissioner of Customs for Agra, George Saunders, installed a line of customs posts along the Ganges and Yamuna rivers from Mirzapur to Allahabad that would eventually evolve into the Inland Customs Line.[8] The main aim was to prevent salt from being smuggled from the south and west but there was also a secondary line running from Allahabad to Nepal to prevent smuggling from the Northwest frontier.[10] The annexation of Sindh and the Punjab allowed the line to be extended north-west by G. H. Smith, who had become Commissioner of Customs in 1834.[10][11] Smith exempted items such as tobacco and iron from taxation to concentrate on salt and was responsible for expanding and improving the line, increasing its budget to 790,000 rupees per year and the staff to 6,600 men.[10] Under Smith, the line saw many reforms and was officially named the Inland Customs Line in 1843.[1]

Inland Customs Line

Smith's new Inland Customs Line was first concentrated between Agra and Delhi and consisted of a series of customs posts at one mile intervals, linked by a raised path with gateways (known as "chokis") to allow people to cross the line every four miles.[1][12] Policing of the barrier and surrounding land, to a distance of 10 to 15 miles (16 to 24 km), was the responsibility of the Inland Customs Department, headed by a Commissioner of Inland Customs. The department staffed each post with an Indian Jemadar (approximately equivalent to a British Warrant Officer) and ten men, backed up by patrols operating 2–3 miles behind the line.[12] The line was mainly concerned with the collection of the salt tax but also collected tax on sugar exported from Bengal and functioned as a deterrent against opium, bhang and cannabis smuggling.[13][14][15]

The end of company rule in 1858 allowed the British government to expand Bengal through territorial acquisitions, updating the line as needed.[16] In 1869 the government in Calcutta ordered the connection of sections of the line into a continuous customs barrier stretching 2,504 miles (4,030 km) from the Himalayas to Orissa, near the Bay of Bengal.[16][17] This distance was said to be the equivalent of London to Constantinople.[18] The north section from Tarbela to Multan was lightly guarded with posts spread further apart as the wide Indus River was judged to provide a sufficient barrier to smuggling. The more heavily guarded section was around 1,429 miles (2,300 km) long and began at Multan, running along the rivers Sutlej and Yamuna before terminating south of Burhanpur.[17][19] The final 794-mile (1,278 km) section reverted to longer distances between customs posts and ran east to Sonapur.[19]

In the 1869–70 financial year the line collected 12.5 million rupees in salt tax and 1 million rupees in sugar duties at a cost of 1.62 million rupees in maintenance. In this period the line employed around 12,000 men and maintained 1,727 customs posts.[17] By 1877 the salt tax was worth £6.3 million (approx 29.1 million rupees)[20] to the British government in India, with the majority being collected in the Madras and Bengal provinces, lying on either side of the customs line.[21]

Great Hedge

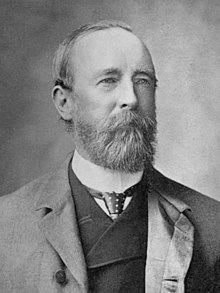

It is not known when an actual live hedge was first grown along the customs line but it is likely that it began in the 1840s when thorn bushes, cut and laid along the line as a barrier (known as the "dry hedge", see also dead hedge), took root.[22][23] By 1868 it had become 180 miles (290 km) of "thoroughly impenetrable" hedge.[24] The original dry hedge consisted mainly of samples of the dwarf Indian plum fixed to the line with stakes.[25] This hedge was at risk of attack by white ants, rats, fire, storms, locusts, parasitic creepers, natural decay and strong winds which could destroy furlongs at a time and necessitated constant maintenance.[25][26] Allan Octavian Hume, Commissioner of Inland Customs from 1867 to 1870, estimated that each mile of dry hedge required 250 tons of material to construct and that this material had to be carried to the line from between 0.25 and 6 miles (0.40 and 9.66 km) away.[27] The amount of labour involved in such a task was one of the reasons that a live hedge was encouraged, particularly as damage required the replacement of around half of the dry hedge each year.[27]

In 1869 Hume, in preparation for a rapid expansion of the live hedge, began trials of various indigenous thorny shrubs to see which would be suited to different soil and rainfall conditions.[28] The result was that the main body of the hedge was composed of Indian plum, babool, karonda and several species of Euphorbia.[29] The prickly pear was used where conditions meant that nothing else could grow, as was found in parts of the Hisar district, and in other places bamboo was planted.[30][31] Where the soil was poor it was dug out and replaced or overlain with better soil and in flood plains the hedge was planted on a raised bank to protect it.[28][30] The hedge was watered from nearby wells or rainwater collected in large, purpose-built trenches and a "well made" road was constructed along its entire length.[1][28]

Hume was responsible for transforming the hedge from "a mere line of persistently dwarf seedlings, or of irregularly scattered, disconnected bushes" into a formidable barrier that, by the end of his tenure as commissioner, contained 448.75 miles (722.19 km) of "perfect" hedge and 233.5 miles (375.8 km) of "strong and good", but not impenetrable hedge.[30] The hedge was nowhere less than 8 feet (2.4 m) high and 4 feet (1.2 m) thick and in some places was 12 feet (3.7 m) high and 14 feet (4.3 m) thick.[30][31] Hume himself remarked that his barrier was "in its most perfect form, ... utterly impassable to man or beast".[32]

Hume also substantially realigned the Inland Customs Line, joining separate sections and removing some of the spurs that were no longer necessary.[31] Where this happened, whole runs of hedge were abandoned, and the men would have to construct a hedge from scratch on the new alignment.[33] The living hedge was terminated at Burhanpur in the south, beyond which it could not grow, and at Layyah in the north where it met the River Indus, whose strong current was judged sufficient to deter smugglers.[34] Historian Henry Francis Pelham compared the use of the Indus in this way to that of the River Main, in modern Germany, for the Roman Limes Germanicus fortifications.[1]

Hume was replaced as Commissioner of Customs in 1870 by G. H. M. Batten who would hold the post for the next six years.[33] His administration saw little realignment of the hedge but extensive strengthening of the existing run, including the building of stone walls and ditch and bank systems where the hedge could not be grown.[1][33] By the end of Batten's first year he had increased the length of "perfect" hedge by 111.25 miles (179.04 km), and by 1873 the central portion between Agra and Delhi was said to be almost impregnable.[26][35] The line was altered slightly in 1875–6 to run alongside the newly built Agra Canal, which was judged a sufficient obstacle to allow the distance between guard posts to be increased to 1.5 miles (2.4 km).[36]

Batten's replacement as Commissioner was W. S. Halsey who would be the last to be in charge of the Great Hedge.[36] Under Halsey's control the hedge grew to its greatest extent, reaching a peak of 411.5 miles (662.2 km) of "perfect" and "good" live hedge by 1878 with a further 1,109.5 miles (1,785.6 km) of inferior hedge, dry hedge or stone wall.[37] The live hedge extended to at least 800 miles (1,300 km) and in places was backed up with an additional dry hedge barrier.[37] All maintenance work was halted on the hedge in 1878 after a decision was made to abandon the line in 1879.[37][38]

Tree and plants

Carissa carandas, an easy-to-grow drought-resistant sturdy shrub that grows in a variety of soil and produces berry size fruits rich in iron and vitamin C which is used for pickle, was one of the shrubs used because it is ideal for hedges, growing rapidly, densely and needing little attention.[39] Senegalia catechu, Zizyphus jujube, prickly pear, and Euphorbia were some of the other shrubs plants and trees used for the hedge.[39]

Staff

The customs line and hedge required a large number of staff to patrol and maintain it. The majority of the staff were Indian, with their officers coming mainly from the British. In 1869 the Inland Customs Department employed 136 officers, 2,499 petty officers and 11,288 men on the line, reaching a peak of 14,188 men of all ranks in 1872, after which staff numbers declined to around 10,000 as expansion slowed and the hedge matured.[40][41] The Indian staff were recruited disproportionately from the Muslim population, who constituted 42 per cent of the customs men.[42] The men were intentionally stationed in areas away from their home towns which, together with their removal of local wood for the hedge, made them unpopular among local people.[42] To encourage co-operation, those Indians who lived in villages near the line were allowed to carry up to 2 pounds (0.9 kg) of salt across for free.[42]

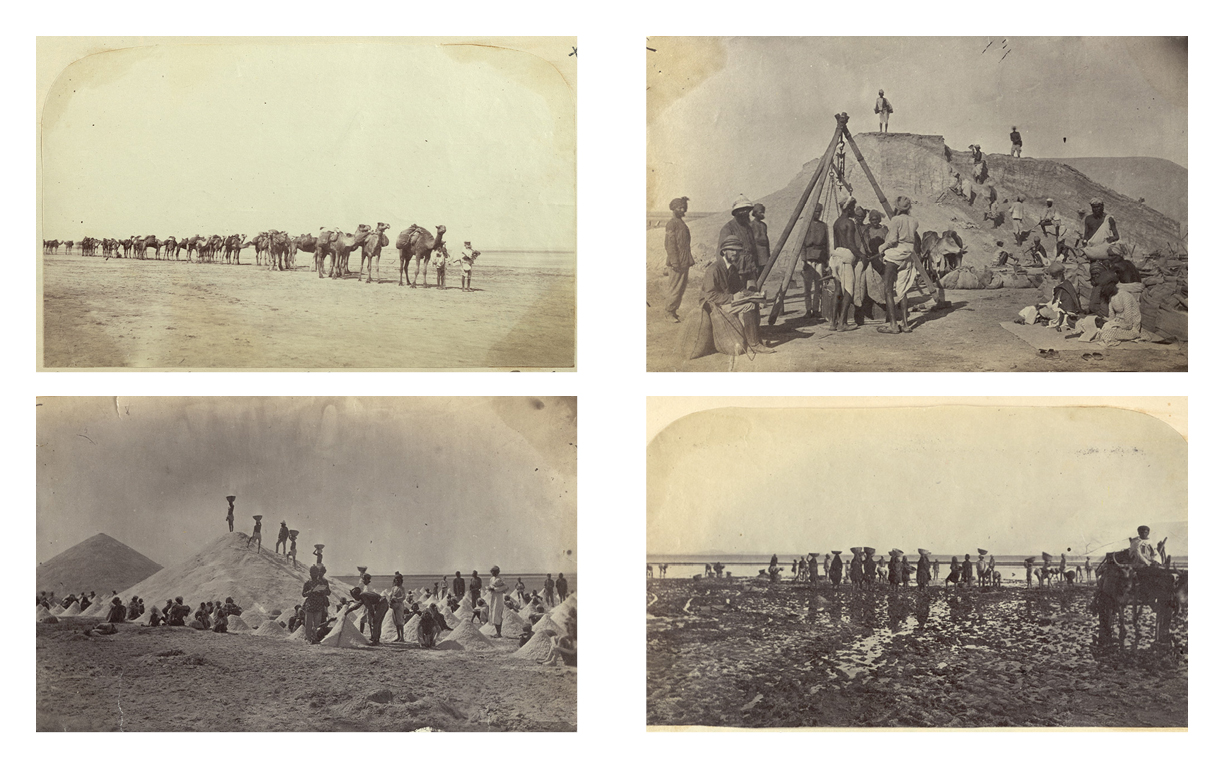

The job of customs man was highly desirable due to its high pay of five rupees per month (agricultural wages were around three rupees a month), which could be topped up with the proceeds from the sale of seized salt.[43] However the men were forced to live away from their families in order to minimise distractions and were not provided with houses, being expected to build their own from mud or wood.[41][44] In 1868 the Inland Customs department allowed the men's families to join them on the line, as the previous order had led to customs men straying from their posts and associating too closely with local women.[44] The men worked twelve-hour days consisting of two equal day and night shifts.[45] The principal tasks were patrolling and maintaining the hedge; in 1869 alone the customs men carried out 18 million miles (29 million km) of patrols, dug 2 million cubic feet (57,000 cubic metres) of earth and carried over 150,000 tons of thorny material for the hedge.[40] There was a fairly high level of turnover in the staff; for example, in 1876-7 more than 800 men left the service. This included 115 customs men who died on the line, 276 dismissed, 30 deserted on duty, 360 failing to rejoin after leave and 23 removed for being unfit.[43]

The officer corps was almost entirely British; attempts to attract Indian men to the post proved unsuccessful, as the officers were required to be fluent in English, and such men could easily find better paid work in other fields.[45] The job was tough, with each officer responsible for 100 men on 10 to 30 miles (16 to 48 km) of the line, and working through Sundays and holidays.[40][45] The officers undertook at least one customs excursion per day on average, weighing and applying tax to almost 200 pounds (91 kg) of goods, in addition to personally patrolling around 9 miles (14 km) of the line.[45] The only other British men they would meet while on the line would typically be officers of adjacent beats and senior officers who visited about three times a year.[45]

Abandonment

Several British viceroys considered dismantling the line, as it was a major obstacle to free travel and trade across the subcontinent.[46] This was partly due to the use of the line for the collection of taxes on sugar (which made up 10 per cent of the revenues) as well as salt, meaning that traffic had to be stopped and searched in both directions.[44] In addition the line had created a confusing number of different customs jurisdictions in the area surrounding it.[47] The viceroys were also displeased with the corruption and bribery which was present in the Inland Customs system, and the way the line came to serve as a symbol of unjust taxes (parts were set on fire during the Indian Rebellion of 1857).[14][19] However, the government could not afford to lose the revenue generated by the line and hence, before they could abolish it, needed to take control of all salt production in India, so that tax could be applied at the point of manufacture.[46]

The Viceroy from 1869 to 1872, Lord Mayo, took the first steps towards abolition of the line, instructing British officials to negotiate agreements with the rulers of princely states to take control of salt production.[48] The process was speeded up by Mayo's successor, Lord Northbrook, and by the loss of revenue caused by the Great Famine of 1876–78 that reduced the land tax and killed 6.5 million people.[48][49] Having secured salt production, British India's Finance Minister, Sir John Strachey, led a review of the tax system and his recommendations, implemented by Viceroy Lord Lytton, resulted in the increase of the salt tax in Madras, Bombay and northern India to 2.5 rupees per maund and a reduction in Bengal to 2.9 rupees.[50] This reduced difference in tax between neighbouring territories made smuggling uneconomical and allowed for the abandonment of the Inland Customs Line on 1 April 1879.[50] The tax on sugar and 29 other commodities had been abolished a year earlier.[51] Strachey's tax reforms continued, and he brought an end to import duties and almost complete free trade to India by 1880.[52] In 1882 Viceroy Lord Ripon finally standardised the salt tax across most of India at a rate of two rupees per maund.[53] However the trans-Indus districts of India continued to be taxed at eight annas (1⁄2 rupee) per maund until 23 July 1896 and Burma maintained its reduced rate of just three annas.[48][54] The equalisation of tax cost the government 1.2 million rupees of lost revenue.[55] The potential for salt to be smuggled from the Kohat (trans-Indus) region meant that the north-western section of the line, some 325 miles long from Layyah to Torbela, continued to be policed by the Department of Salt Revenue in Northern India until at least 1895.[56]

Impact

On health

The use of the customs line to maintain the higher salt tax in Bengal is likely to have had a detrimental effect on the health of Indians through salt deprivation.[57] The higher prices within the area enclosed by the line meant that the average annual salt consumption was just 8 pounds (3.6 kg) compared with up to 16 pounds (7.3 kg) outside the line.[58] Indeed, the British government's own figures showed that the barrier directly affected salt consumption, reducing it to below the level that regulations prescribed for English soldiers serving in India and that supplied to prisoners in British jails.[59] The consumption of salt was further lowered during the periods of famine that affected India in the 19th century.[60]

It is impossible to know how many died from salt deprivation in India as a result of the salt tax as salt deficiency was not often recorded as a cause of death and was instead more likely to worsen the effects of other diseases and hinder recoveries.[60] It is known that the equalisation of tax made salt cheaper on the whole, decreasing the tax imposed on 130 million people and increasing it on just 47 million, leading to an increase in the use of the mineral.[61] Consumption grew by 50 per cent between 1868 and 1888 and doubled by 1911, by which time salt had become cheaper (relatively).[62]

The rate of salt tax was increased to 2.5 rupees per maund in 1888 to compensate for the loss of revenue from falling silver prices, but this had no adverse effect on salt consumption.[55] The salt tax remained a controversial means of collecting revenue and became the subject of the 1930 Salt Satyagraha, a civil disobedience movement led by Mohandas Gandhi against British rule. During the Satyagraha Gandhi and others marched to the salt producing area of Dandi and defied the salt laws, leading to the imprisonment of 80,000 Indians. The march drew significant publicity to the Indian independence movement but failed to get the tax repealed. The salt tax would finally be abolished by the Interim Government of India, led by Jawaharlal Nehru, in October 1946.[63] The government of Indira Gandhi overlaid much of the old route with roads.[64]

On liberty

Sir John Strachey, the minister whose tax review led to the abolition of the line, was quoted in 1893 describing the line as "a monstrous system, to which it would be almost impossible to find a parallel in any tolerably civilised country".[18]

This has been echoed by modern writers such as journalist Madeleine Bunting, who wrote in The Guardian in February 2001 that the line was "one of the most grotesque and least well known achievements of the British in India".[65]

The massive scale of the undertaking has also been commented upon, with both Hume, the customs commissioner, and M. E. Grant Duff, who was Under-Secretary of State for India from 1868 to 1874, comparing the hedge to the Great Wall of China.[1][30] The abolition of the line and equalisation of tax has generally been viewed as a good move, with one writer of 1901 stating that it "relieved the people and the trade along a broad belt of country, 2,000 miles long, from much harassment".[54] Sir Richard Temple, governor of the Bengal and Bombay Presidencies, wrote in 1882 that "the inland customs line for levying the salt-duties has been at length swept away" and that care must be taken to ensure that the "evils of the obsolete transit-duties" did not return.[66] However, the same year, the India Salt Act of 1882 explicitly prohibited Indians from collecting or selling salt and continued to limit access to the vital product at affordable prices.[67]

On smuggling

The Line was intended to prevent smuggling, and in this respect it was fairly successful.[68] Smugglers who were caught by customs men were arrested and fined around 8 rupees, those that could not pay being imprisoned for around six weeks.[69] The number of smugglers caught increased as the line extended and was built up. In 1868 2,340 people were convicted of smuggling after being caught on the line, this rose to 3,271 smugglers in 1873–74 and to 6,077 convicted in 1877–78.[43][70]

Several methods of smuggling were employed. Early on, when patrols were patchy, large scale smuggling was common, with armed gangs breaking through the line with herds of salt-laden camels or cattle.[71] As the line was strengthened, smugglers changed tactics and would try to disguise salt and bring it through the line or throw it over the hedge.[71] Sometimes smugglers hid salt within the jurisdiction of the customs department to collect the 50 per cent finders fee.[72]

Clashes between smugglers and customs men were often violent. Customs officials "harassed Indian people and exhorted bribes".[67] Many of the smugglers died, with examples including one drowning while trying to escape by swimming an irrigation tank and another accidentally killed by other smugglers during a fight with customs men.[73] In September 1877, one large skirmish occurred when two customs men attempted to apprehend 112 smugglers and were both killed.[70] Many of the gang were later caught and either imprisoned or transported.[73]

Rediscovery

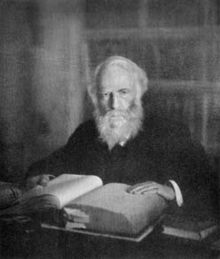

Despite its scale, the customs line and associated hedge were not widely known in either Britain or India, the standard histories of the period neglecting to mention them.[32] Roy Moxham, a conservator at the University of London library, wrote a book on the customs line and his search for its remains that was published in 2001. This followed his finding, in 1995, of a passing mention of the hedge in Major-General Sir William Henry Sleeman's work Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official.[32] Moxham looked up the hedge in the India Office Records of the British Library and determined to locate its remnants.[74]

Moxham conducted extensive research in London before making three trips to India to look for any remains of the line.[75] In 1998 he located a small raised embankment in the Etawah district in Uttar Pradesh which may be all that remains of the Great Hedge of India.[76] Moxham's book, which he claims to be the first on the subject, details the history of the line and his attempts to locate its modern remains.[75] The book was translated into Marathi by Anand Abhyankar in 2007 and into Tamil by Cyril Alex in 2015.[77][78]

In July 2015, the Children's BBC channel outlined the hedge on Horrible Histories,[79][80] watched that week by 207,000 viewers.[81]

Artist Sheila Ghelani and Sue Palmer produced live art performances of a piece called "Common Salt", about the hedge. Their book on the subject was published in July 2021 by Live Art Development Agency.[67]

In August 2021, journalist Kamala Thiagarajan wrote about the hedge on BBC Future's "Lost Index" series.

Moxham was recently invited to a conference on Nuclear Energy in Verdun, France to speak about the Great Hedge. "They were intrigued by how such a big project could have disappeared from memory in such a short time," says Moxham. The delegates saw it as proof enough that the world could forget anything – including the cost of nuclear warfare or the grave dangers posed by improperly disposing of radioactive waste – all of which could have severe consequences if ever erased from public memory.[82]

See also

Supriya Ambwani —

The Empire's Salt Tax: Uncovering the Forgotten Hedge of India

The Great Hedge of India, also known as the Indian Salt Hedge,

was a particularly insidious project. It supported the Indian Salt Tax,

perhaps the cruellest form of extraction in the British Empire, which

levied excessive taxes on the essential commodity. The tax propped up

the British colonial project, while exacerbating state-sponsored

famines, killing millions and sickening millions more not only by

starvation but also by salt deprivation.1 Sir John Strachey, a British civil servant quoted in a footnote to Major-General Sir W. H. Sleeman’s Rambles and Recollections of an Indian Official, offers an account of the Hedge:

To secure the levy of a duty on salt… there grew up gradually a monstrous system, to which it would be almost impossible to find a parallel in any tolerably civilized country. A Customs line was established which stretched across the whole of India, which in 1869 extended from the Indus to the Mahanadi in Madras, a distance of 2,300 miles; and it was guarded by nearly 12,000 men… It would have stretched from London to Constantinople… It consisted principally of an immense impenetrable hedge of thorny trees and bushes.2

The Great Hedge of India was a vegetated, physical manifestation

of this “monstrous system,” explicitly designed to sow divisions and

extract resources. As it was eventually cleared from the landscape, it

also disappeared from people’s memories.

Although the Indian subcontinent has always had enough salt to support its needs via trade, large parts of the population live too far from sources of salt to make their own.3 The British exploited these geographic differences by heavily taxing salt in the areas they controlled. Under the governance of the East India Company, the British sought to build a physical barrier to stop desperate residents from smuggling cheaper salt in from other places like the Sambhar Salt Lake, in present-day Rajasthan.4 The Great Hedge of India was thus established in the 1840s as a form of deterrence and control, part of the Inland Customs Line, which divided the Indian subcontinent until the British assumed unified control over its disparate regions.5 The Customs Line surrounded the Bengal Presidency, the early seat of the British Empire in India, to tax all the salt that entered the region and all the sugar and salt that left it.6

Excluding a few stone walls where ground conditions constrained planting, the 2,504-mile-long Hedge was composed entirely of living vegetation.7 At its peak from 1869 to 1879, it stretched from the foothills of the Himalayas to the Orissa coast across parts of modern-day Pakistan and India.8 The Hedge was described as “utterly impassable to man or beast” and was heavily guarded by thousands of officers stationed at chowkies (guard posts) before it was abandoned on April 1, 1879.9 Made up of trees and shrubs chosen specifically for their impenetrability, it was a true feat of landscape design supported by incredible amounts of underpaid labour.10

For nearly half the nineteenth century, the Hedge attracted legions of British civil servants, labourers, and security guards. There is little information about who had the original idea of building a hedge across India, but historical records show that Allan Octavian Hume, a former commissioner of Inland Customs, played an outsize role in strengthening it. The Great Hedge not only impacted its immediate surroundings and those who lived there but also had far-reaching effects. However, despite the vast size of this living infrastructure and the violence it enacted, its existence quickly disappeared from historical memory, erasing the real stories of the people and landscapes it affected.

What little information is available about the Hedge is due to Roy Moxham’s seminal 2001 book The Great Hedge of India: The Search for the Living Barrier That Divided a People. Moxham’s book uncovered the existence of the forgotten Hedge and transferred its fragmented oral histories and written reports into a combined history and travelogue.11 In 1997, Moxham found a map of the Agra District at the Royal Geographical Society in Kensington Gore dated April 1879, when the Customs Line was abandoned.12 This map provided him with definitive proof of the existence and location of the project, and it remains the clearest representation of the Hedge given the lack of academic research on the subject. Contemporary researchers are now building off of Moxham’s work: Aisling M O’Carroll’s ongoing research project “Tracing the Great Salt Hedge” not only searches for the physical remnants of the Hedge but also considers its larger-scale territorial impacts;13 the journalist Kamala Thiagarajan’s article, “The Mysterious Disappearance of the World’s Longest Shrubbery,” rehashes Moxham’s work for readers of BBC's “Lost Index” series.14 However, the scarcity of sources documenting the Hedge and its impacts is a reminder of how the colonial state enacted violence by controlling written chronicles of its reign in a society that traditionally relied on oral histories to communicate with future generations.

The Hedge’s erasure from historical narratives about the British Raj belies its scale and influence on the Empire and the horrors it wrought, raising questions about how quickly people forget the events that have shaped their present. The omission of such histories thus reproduces the violence of colonialism by denying access to past knowledge that continues to haunt the present. Moxham’s work is pivotal, and remains the only major source of research on the Hedge. Its singularity invites further critical research to help expand and refine the stakes of the subject. This essay illuminates the story of the Great Hedge of India, which helped fill the coffers of the British Empire with salt taxes, by examining its intertwined landscapes.15 Tracing the Hedge and its legacy through two sites, the Sambhar Lake and Rothney Castle, with the help of Moxham’s work, will hopefully render visible the scope of its destruction and underline how critical the preservation of this history is to understanding how natural environments continue to be weaponized.

A major source of the salt that crossed the Hedge was the

Sambhar Salt Lake in Rajasthan, which has provided the mineral to the

subcontinent for centuries. In the dry season, water evaporates from the

lake, leaving behind salt sheets that are harvested and exported. The

inland saline lake is also a critical biodiversity zone—host to many

migratory birds, including flamingos.16

It is now gravely threatened because of pollution, land-use change, and

climate change. Nonetheless, it remains an exceptionally important

cultural and inancial resource, and an environmentally sensitive

habitat.

The various myths surrounding the Sambhar Salt Lake’s creation highlight its historicity and importance. In a popular story, the goddess Shakambhari Devi gifted a regional king a large tract of land covered in silver. The king requested that the goddess replace the silver with salt, a more precious commodity, leading to the creation of the 230-square-kilometre salt lake, which still has a temple dedicated to Shakambhari Devi on its shore.17 In more easily verifiable historical accounts, the Mughals extracted salt from the lake for the entirety of their rule, starting with Babur in the early sixteenth century, before handing it over to the rulers of Jaipur and Jodhpur around the mid-nineteenth century.18 On May 1, 1871, the British forcibly took over the saltworks at the lake, gaining control of “the principal source of salt going into the Bengal Presidency from outside the Customs Line.”19 Seven years later, A. O. Hume helped transfer all salt rights from the Princely States of Rajasthan to the British Empire by paying the rulers a nominal sum of money, a process presumably accelerated by imperial threats of property seizure and the takeover of kingdoms.20

With the seizure of the Sambhar Lake saltworks, the British refined their tactics for controlling those engaged in the harvesting of salt. Historical photographs taken in the 1870s housed at the British Library’s archives show Indian salt workers, or malangis, labouring under the gaze of British overseers.21 Moxham writes about the plight of malangis not only in Sambhar but also in other salt-producing regions of the country, like the rock salt mines in Punjab and the coasts.22 Starting in the 1770s, salt workers, who often belonged to families of independent salt-makers, “had suddenly found their business expropriated, and been forced to work for pitiful wages” under the new system of contracts and leases.23 Although stories about their exploitation outraged members of the British public, the backlash was clearly not enough to ensure the malangis and their descendants greater dignity of labour—even in independent India.24 The salt that the malangis produced for those pitiful wages would have to cross the Great Hedge of India to be heavily taxed and sold to British Indian subjects at highly exploitative rates. From the late eighteenth century to at least 1836, the salt tax was around a sixth of a rural labourer’s income; at its worst in 1823, it went up to six months’ wages.25 Furthermore, locals were subject to new methods of surveillance and exploitation. Customs officers were stationed at chowkies near saltworks to prevent salt from being smuggled out.26 The Empire incentivised the officers to abuse their positions by paying them a pittance, thus tacitly encouraging them to extort the locals.

As a form of colonial wealth extraction built on slavery and

subjugation, the salt tax continues to affect national economies decades

after the sun finally set on the British Empire. Its profitability

encouraged the colonial state to invest enormous amounts of labour and

capital into the huge and destructive landscape design intervention that

was the Great Hedge of India. It is estimated that almost 14,000 people

worked for the Customs Line in 1869, though the labour of villagers who

planted the Hedge is not precisely documented.27

Even more work went into a previous iteration of the Hedge, which was

made up of dry shrubbery and required around 250 tons of material per

mile.28 According to Hume’s 1867−1868 report, dry hedges were destroyed by pests (like white ants), storms, fires, and natural decay.29

These failures encouraged the British administration to grow a live

hedge, an impenetrable barrier to keep an essential commodity from the

starving masses. As Hume pointed out in a subsequent 1869−1870 report, a

live hedge requires high labour inputs in its initial years but little

maintenance once it is established.30

Its existence was a point of pride for the British Empire. Hume

announced that the Hedge was to the Customs Line “what the Great Wall

once was to China, alike its greatest work and its chiefest safeguard.”31

Relentless attention to local vegetation and climatic conditions ensured that the Hedge thrived. In places where the land was incapable of supporting the Hedge, soil was imported. The use of a vegetated barrier perhaps served to visibly soften the brutality of the Customs Line in the public consciousness, but there was nothing benign about its design. Workers whose names have long been forgotten collected seeds from thorny indigenous plants that would grow fast and strong, selected for their ability to inflict maximum damage on those who tried to sneak across the barrier.32 The Hedge consisted of plant species like: babool (Acacia nilotica), Indian plum (Ziziphus mauritiana), karonda (Carissa carandas), nagphani (Opuntia, three species), thuer (Euphorbia, several species), thorny creeper (Guilandina bonduc), karira (Capparis decidua), and madar (Calotropis gigantea).33 Ridges were raised and trenches were dug to ensure both adequate drainage and rainwater collection.34 The resilience of live plants—or perhaps the maintenance that supported them—helped the Hedge endure environmental degradation.35 According to a commissioner of the Customs Line, the Hedge was “in its most perfect form… ten to fourteen feet in height, and six to twelve feet thick, composed of closely clipped thorny trees and shrubs.”36 It truly was an ecological marvel—though one designed to oppress.

After the Great Famine of 1876−1878, which killed 6.5 million people in British India,37 the British attempted to standardize salt taxes across the country, eliminating the market for smuggled salt and the need for a Customs Line.38 This was not born out of an altruistic desire to stop state-sponsored genocide—once the British controlled all of India, including the Princely States, the labour and money that went into maintaining the Hedge seemed wasteful.39 The Hedge was abandoned and gradually replaced by roads, housing, and farms—a stunning obliteration of such a carefully tended landscape feature. The natural forces that the British had fought so hard to keep at bay eventually took over, as did neighbouring landowners eager to expand their holding and government officials zealously building highways.40 Although some locals at the sites Moxham visited remembered that a hedge once existed there, the Hedge itself was largely lost to public memory until Moxham traced its path and found its remnants—a grassy line that gave way to a 40-foot-wide embankment covered in towering thorny shrubs before disappearing again—in Etawah, Uttar Pradesh.41 More recently, Aisling O’Carroll appears to have found a section of the Hedge in Palighar, and her research promises to uncover more knowledge of this forgotten landscape.42

The Hedge may have disappeared, but the wealth accrued by the

repressive salt taxes that it helped enforce, along with other colonial

spoils, continues to support the United Kingdom and many of its

intergenerationally wealthy citizens. One of the people who drew a

salary from the management of the Hedge was Hume.43

After a radical professional transformation, in which he went from

being a member of the colonial administration to helping found the

Indian National Congress to advocate for Indian independence, Hume was

forced out of the British civil services and bought an estate called

Rothney Castle in Shimla. He spent freely from his personal funds to

make Rothney Castle, with its sprawling grounds, “the most magnificent

building in Shimla.”44

A longtime enthusiast of nature in the nineteenth-century sense (more

interested in taxidermy than preserving live animals in their habitat),

Hume had used his horticultural knowledge to strengthen the Hedge,

growing it to near perfection.45

Given this expertise, he undoubtedly played a significant role in the

castle’s design, expansion, and upkeep—no small feat for an estate

spread over 17,500 square meters in mountainous terrain. He slaughtered

thousands of birds during his time as commissioner—many of which he

undoubtedly killed along the Hedge—and gifted 63,000 dead birds and

15,500 eggs to the Natural History Museum in London.46

Long after his exploits along the Hedge, Hume displayed parts of his

collection at Rothney Castle, where he lived for a few years before

returning to England to retire.47

Despite his support for Indian independence, Hume’s relationship to Rothney Castle in many ways reflects the ecologically and socially extractive practices of colonial governance that were bound up in the Great Hedge. Landscapes have long been altered in the Indian subcontinent, but the British sought to control nature to an obsessive degree. Hume’s work illustrates the jarring disconnect between the colonial fascination with the natural world and the violence unleashed to express “appreciation” for it. Hume slaughtered thousands of birds in what he saw as enthusiasm for avian fauna. Similarly, he used his extensive horticultural knowledge to drive millions of people to starvation instead of wielding it to restore landscapes ravaged by his government or support greater food security for a famished populace.Most importantly, Hume was able to leave India to return to England in 1894, while the millions of people affected by his and his administration’s policies had no choice but to deal with the repercussions. After his departure, Rothney Castle passed through various private owners, none of whom maintained it as well as its most famous inhabitant. Today, Rothney Castle lies overgrown and abandoned, an apt metaphor for the Hedge that funded its former glory.48

The Great Hedge of India has been destroyed and largely

forgotten by the descendants of those it oppressed. However, the fortune

the British Empire raised through its salt tax, extracted from the

blood of its subjects, persists via intergenerational wealth transfer

and money held by both the State and the Crown. The colonial regime had

obvious reasons to obscure its harshest cruelties in British India,

choosing instead to amplify its meagre claims of civilising hordes of

natives. What seems more shocking is that memories of the Hedge appear

to have been wiped out of contemporary Indian accounts of colonisation.

It is simply not mentioned in history books or referenced in discussions

about the Salt Tax.

Landscapes, as Simon Schama explains in his book Landscape and Memory, are inextricably linked to human recollections.49 “Before it can ever be a repose for the senses, landscape is the work of the mind. Its scenery is built up as much from strata of memory as from layers of rocks,” he writes.50 In the case of the Hedge, multiple generations forgot a visible landscape feature and the trauma it unleashed on the people it was designed to oppress. Even in a culture built around oral traditions, the Hedge’s disappearance is surprising; its omission (perhaps deliberate) from British colonial histories is even more jarring given the Empire’s obsession with documenting the minutiae of its reign.

The disappearance—both cultural and physical—is testimony to the

brevity of human memories and the transient nature of landscapes. It is

also a warning to us as we contend with shifting baselines in the face

of the climate crisis. Our histories are tied to the landscapes we

inhabit. It has become clear that our futures are also affected by our

past and present landscape manipulations. The cycles of destruction and

decay that swept away the Hedge and its associated landscapes seem more

predictable than our collective inability to comprehend the potential

horrors of the ostensibly innocuous profession of landscape design.

Those of us who work with the built and natural environments must be

attentive to landscape histories and cognisant of the violence that

landscapes can inflict. The Hedge created a diverse and vibrant

ecosystem, a stated goal of ecologists and landscape architects today.

It also starved millions and ranks amongst the cruellest human-made

structures in history. Unless we grapple with the power structures that

helped create and sustain the Hedge and the collective amnesia that

absolved its architects of responsibility for its excesses, we are

doomed to continue greenwashing borders and enclosures. The Greatest

Living Wall in history is dead. Where will it be raised next?

For more on how the British Empire utilized famine to entreAcknowledgement: A version of this essay was originally written for “Theories of Landscape as Urbanism,” taught at the Harvard University Graduate School of Design in Fall 2021 by Professor Charles Waldheim and Teaching Fellow Hanan Kataw.