| ||||||||

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Royal_Indian_Navy_Mutiny

THE AIR FORCE MUTINY – 1946 :- The Forgotten Mutiny that ...

Mutiny in the British Indian Army Jabalpur-1946

The Great Royal Indian Navy Mutiny of 1946 and beyond – A ...

Mutiny in the British Indian Army Jabalpur

On the 26th February 1946 120 army men of the ‘J’ company of the Signals Training Centre (STC), Jabalpur rebelled against their British superiors and broke free from their barracks directly due to the naval revolt. Part of a radio signalling unit, they were sick and...........................

HMIS Talwar at Bombay Harbour.

The RIN Mutiny started as a strike by ratings of the Royal Indian Navy on 18 February in protest against general conditions. The immediate issue of the mutiny was conditions and food, but there were more fundamental matters such as racist behaviour by Royal Navy personnel towards Indian sailors, and disciplinary measures being taken against anyone demonstrating pro-nationalist sympathies. By dusk on 19 February, a Naval Central Strike committee was elected. Leading Signalman M.S Khan and Petty Officer Telegraphist Madan Singh were unanimously elected President and Vice-President respectively. The strike found immense support among the Indian population, already gripped by the stories of the Indian National Army. { read about I.N.A.:-http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Indian_National_Army} The actions of the mutineers was supported by demonstrations which included a one-day general strike in Bombay. The strike spread to other cities, and was joined by the Royal Indian Air Force and local police forces. Naval officers and men began calling themselves the "Indian National Navy" and offered left-handed salutes to British officers. At some places, NCOs in the British Indian Army ignored and defied orders from British superiors. In Madras and Pune, the British garrisons had to face revolts within the ranks of the Indian Army. Widespread rioting took place from Karachi to Calcutta. Notably, the mutinying ships hoisted three flags tied together — those of the Congress, Muslim League, and the Red Flag of the Communist Party of India (CPI), signifying the unity and demarginalisation of communal issues among the mutineers.

The mutiny was called off following a meeting between the President of the Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC), M. S. Khan, and Vallab Bhai Patel

of the Congress, who had been sent to Bombay to settle the crisis. Patel issued a statement calling on the strikers to end their action, which was later echoed by a statement issued in Calcutta by Mohammed Ali Jinnah

on behalf of the Muslim League. Under these considerable pressures, the strikers gave way. However, despite assurances of the good services of the Congress and the Muslim League widespread arrests were made. These were followed up by courts martial and large scale dismissals from the service. None of those dismissed were reinstated into either of the Indian or Pakistani navies after independence.

Events of the Mutiny:-

After the Second World War, three officers of the Indian National Army (I.N.A.), General Shah Nawaz Khan, http://indianindependancemovementphotos.blogspot.com/2009/07/shah-nawaz-khan-general-indian-freedom.html

Colonel Prem Sehgal

and Colonel Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon

Freedom fighter, Indian National Army colonel and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose's close associate G S Dhillon, in Delhi on December 22, 1950. |

Rare images of the November 1945 Indian National Army (Azad Hind Fauj) trials from photojournalist Kulwant Roy’s work, as documented by Aditya Arya in the visual archive History in the Making.

In his book Azaadi!, English author Reginald Massey, who was born and raised in pre-Partition Lahore, recalls the reception of three INA generals shortly after they were acquitted, which he witnessed as a teenager:

There were thousands who greeted them at the historic Minto Park. In unison they chanted loudly:

“Chaalis crore-on ki awaaz! (Forty crore people shout in unison!) (Editor’s note: India’s population was 40 crores – 400 million – at that time.)

Sehgal – Dhillon – Shah Nawaz!!“

When the Japanese routed the Allies in south east Asia, they took some 60,000 soldiers of the British Indian army prisoners. 20,000 of them agreed to switch sides and go to war against their former masters — the British, in the Indian National Army under the command of Subhas Chandra Bose.

After the Allies won the war, the INA soldiers once again became prisoners — this time of the British. The military logic of the British India government was clear — they considered the INA joinees to be traitors, deserving of severe punishment. The furious, self-righteous government decided to make an example of the the INA leaders by performing their court martial and treason trial — the first one was to take place in Delhi’s iconic Red Fort, the same place from where Bose promised that INA would declare India’s independence.

Of the three INA generals arraigned for the first trial were a Hindu (Prem Kumar Sehgal), a Muslim (Shah Nawaz Khan) and a Sikh (Gurbaksh Singh Dhillon). The cause of their defence was taken up by the Congress, whose leaders toured the country, mobilizing support for the soldiers awaiting the trial. Jawaharlal Nehru was among the defence lawyers. While the defense lost the case and the defendants were declared guilty, the British sensed the popular mood, including within the British India Army, which was far from unsympathetic toward the INA. This was a time when the Muslim League was on the threshold of winning Pakistan, by dividing the territory of British India along communal lines. Yet, Indians, irrespective of religion were united in feeling that the ruling power was out for vengeance and in heaping curses upon it. The government was forced to commute the sentences of the convicted trio and release them.

Images

Photojournalist Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) had been among the handful of Indians who lived and worked through the exciting times before and after India’s Independence. His archive of mostly unpublished prints and negatives lay forgotten in boxes for more than 20 years after his death in 1984 until they were discovered by Aditya Arya, to whom he had left his work. Here are a few snapshots from the time around the INA trials of 1945 that Roy captured through his lens:

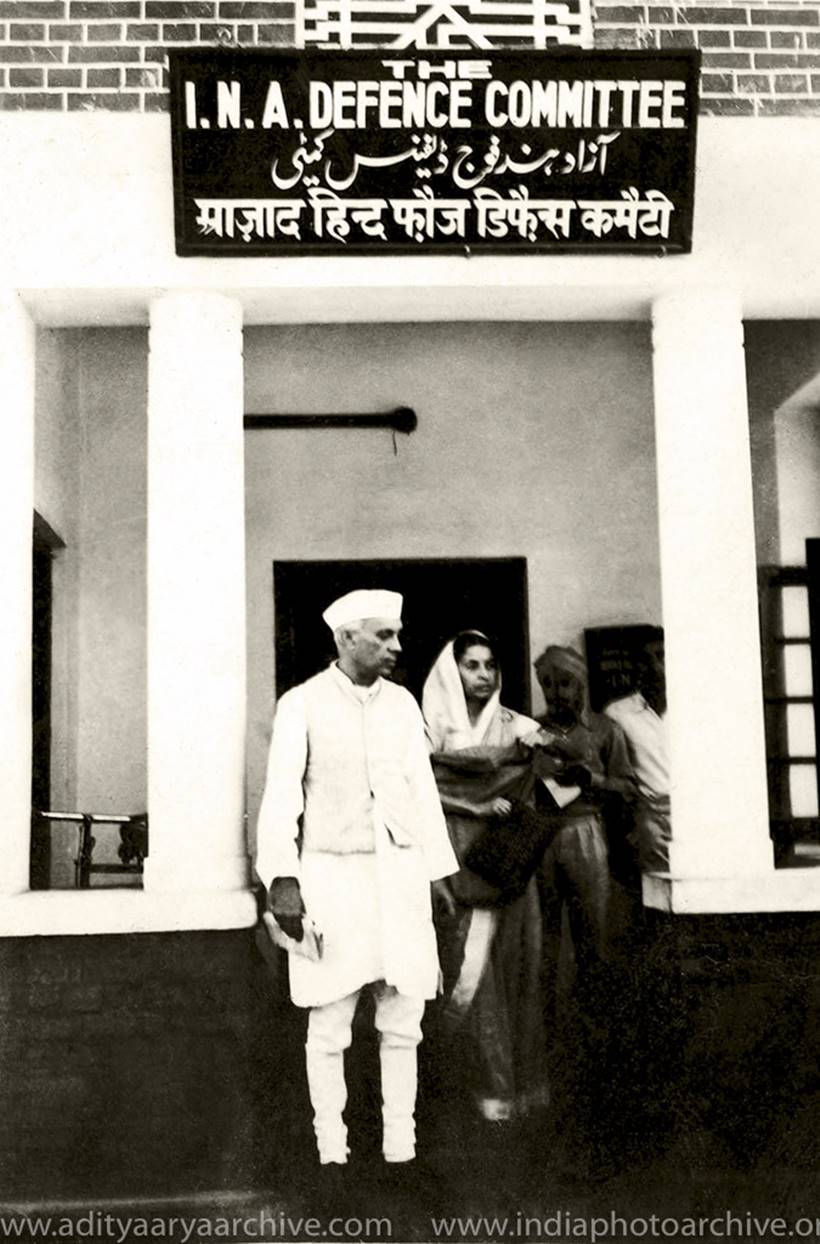

Jawaharlal Nehru with the members of the INA Defence Committee,

1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya

Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru with the members of the INA Defence Committee,

1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya

Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

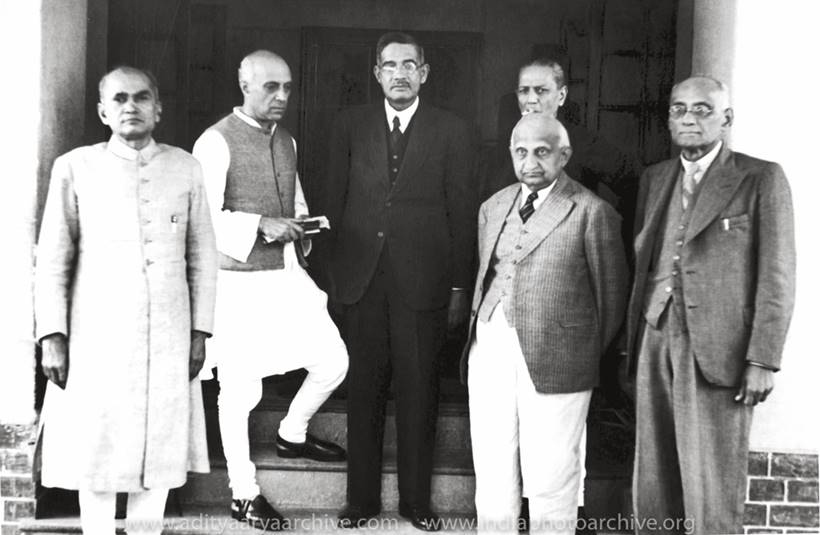

Members of the Defence Committee, R.B. Badri Dass, Justice Acchru Ram

and Asaf Ali discussing the charge sheet of the INA cadre at Delhi Red

Fort, 1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya

Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Members of the Defence Committee, R.B. Badri Dass, Justice Acchru Ram

and Asaf Ali discussing the charge sheet of the INA cadre at Delhi Red

Fort, 1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya

Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru emerging from the Defence Committee office. Photo by

Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives,

Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru emerging from the Defence Committee office. Photo by

Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives,

Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

General Mohan Singh who formed the First I.N.A in Far East is seen here

while chatting with Mrs. Ehsan Qadir, wife of Capt. Ehsan Qadir of the

INA. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya

Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

General Mohan Singh who formed the First I.N.A in Far East is seen here

while chatting with Mrs. Ehsan Qadir, wife of Capt. Ehsan Qadir of the

INA. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya

Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

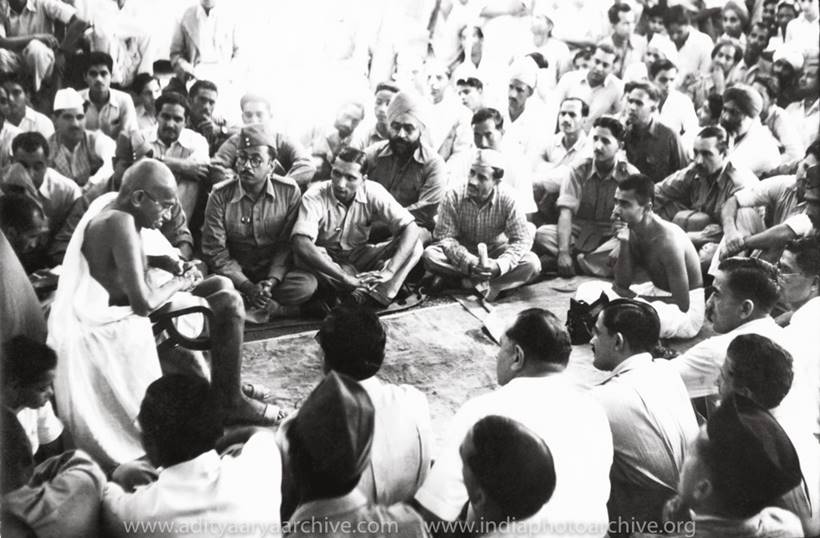

Mahatma Gandhi

with soldiers of the INA, 1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and

photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo

Archive Foundation.

Mahatma Gandhi

with soldiers of the INA, 1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and

photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo

Archive Foundation.

Captain Ram Singh, who had composed the patriotic song ‘Kadam Kadam

Badhaye Ja’ plays the violin for Gandhiji at the Harijan Colony,

1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya

Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Captain Ram Singh, who had composed the patriotic song ‘Kadam Kadam

Badhaye Ja’ plays the violin for Gandhiji at the Harijan Colony,

1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya

Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru attends a meeting of Gandhiji and INA soldiers,

1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya

Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru attends a meeting of Gandhiji and INA soldiers,

1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya

Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

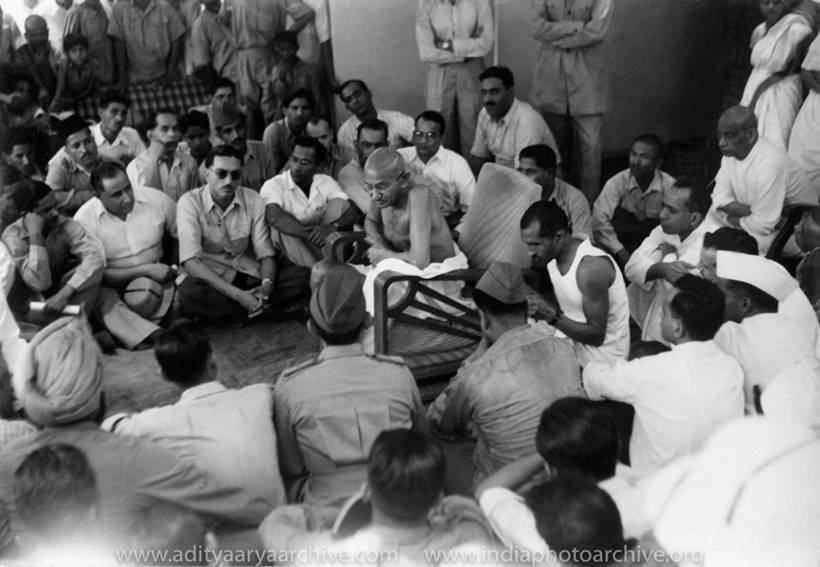

An engrossed audience listening to Gandhiji in this rare documentation

of the meeting, 1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit :

Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive

Foundation.

An engrossed audience listening to Gandhiji in this rare documentation

of the meeting, 1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit :

Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India Photo Archive

Foundation.

Also seen attending the meeting is Sardar Patel, 1945. Photo by Kulwant

Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman &

Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Also seen attending the meeting is Sardar Patel, 1945. Photo by Kulwant

Roy (1914-1984) and photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman &

Trustee, India Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru with members of the INA enquiry committee at the

Constitution Club, New Delhi (1945). Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984)

and photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India

Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru with members of the INA enquiry committee at the

Constitution Club, New Delhi (1945). Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984)

and photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India

Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru with INA cadre, 1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984)

and photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India

Photo Archive Foundation.

Jawaharlal Nehru with INA cadre, 1945. Photo by Kulwant Roy (1914-1984)

and photo credit : Aditya Arya Archives, Chairman & Trustee, India

Photo Archive Foundation.

Kulwant Roy gifted his work to Aditya Arya, who has since archived them under the aegis of the India Photo Archive Foundation. Arya can be reached at adityaarya@adityaarya.com

for "waging war against the King Emperor", i.e. the British sovereign personifying British rule. The three defendants were defended at the trial by Jawaharlal Nehru,

Bhulabhai Desai

and others. Outside the court, the trials inspired protests and discontent among the Indian population, who came to view the defendants as revolutionaries who had fought for their country.READ ABOUT THE TRIALS:-http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/INA_trials

HMIS Hindustan at Bombay Harbour after the war

Image: HMIS Hindustan at Bombay harbour ...

HMIS Hindustan at Bombay Harbour after the war.

The mutiny was initiated by the ratings of Indian Navy on 18 February 1946. It was a reaction to the treatment meted out to ratings in general and the lack of service facilities in particular. On 16 January 1946, a contingent of 67 ratings of various branches arrived at Castle Barracks, Mint Road, in Fort BOMBAY(Mumbai). This contingent had arrived from the basic training establishment, HMIS Akbar, located at Thane, a suburb of Bombay, at 1600 in the evening. One of them Syed Maqsood Bokhari went to the officer on duty informed him about the galley (kitchen) staff of this arrival. The sailors were that evening alleged to have been served sub-standard food. Only 17 ratings took the meal, the rest of the contingent went ashore to eat in an open act of defiance. It has since been said that such acts of neglect were fairly regular, and when reported to senior officers present practically evoked no response, which certainly was a factor in the buildup of discontent. The ratings of the communication branch in the shore establishment, HMIS Talwar, drawn from a relatively higher strata, harboured a high level of revulsion towards the authorities, having complained of neglect of their facilities fruitlessly.

The INA trials, the stories of Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose

, as well as the stories of INA's fight during the Siege of Imphal and in Burma were seeping into the glaring public-eye at the time. These, received through the wireless sets and the media, fed discontent and ultimately inspired the sailors to strike. In Karachi, mutiny broke out on board the Royal Indian Navy ship, HMIS Hindustan off Manora Island. The ship, as well as shore establishments were taken over by mutineers. Later, it spread to the HMIS Bahadur

|

The lesser-known Mutiny

THE trauma experienced during those four days of the Rin Mutiny in February, 1946 was a source of tension. In fact the situation was more sensitive than the one that arose from the actual combat condition prevailing in the north Arabian sea during the India-Pakistan conflict in 1971. The mutiny was

initiated by the ratings of Indian Navy during early 1946. It was a

reaction against the treatment meted to ratings in general and the

lack of service facilities in particular. On January 16, 1946, a

contingent of 67 ratings of various branches arrived at Castle

Barracks, Mint Road, in Fort Mumbai. This contingent had arrived from

the basic training establishment, HMIS Akbar, located at Thane a

suburb of Mumbai at 1600 in the evening. The officer on duty informed

the galley (kitchen) staff of this arrival. Quite casually, the duty

cook, without winking an eyelid, took out 20 loaves of bread from the

large cupboard and added three litres of tap water to the mutton curry

as well as the gram dal which was lying already cooked before

as per the morning strength of the ratings. Every one associated with

each wing of administration in those days had such a mindset that no

one bothered. Nothing more was required to be done in such cases. On

that day, only 17 ratings ate the watery, tasteless meals while the

rest went ashore and ate. Such daily cases of neglect, when reported

to senior officers present, practically evoked no response and the

discontentment continued to build up. The better educated ratings of

communication branch in the shore establishment, HMIS Talwar, located

in Mumbai had been complaining of neglect of their facilities and

harboured a high level of revulsion towards the authorities. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Inspired by the patriotic fervour sweeping the country, the movement started taking a political turn. During the second week of February, 1946, my ship was alongside the outer breakwater. One fine early morning, I noticed about 20 junior ratings surrounding the main duty- free canteen located close to the smithy shop inside the naval dockyard in Mumbai. This large canteen was a part of an international chain of canteens run by the royal navy and was well-stocked with choicest brands of foreign liquor, cheeses, caviar, cigarettes etc mostly imported. About four ratings forced themselves into the store and came out with cartons of cigarettes, cameras and electric irons etc. It was followed by another rush of ratings who now were holding boxes of scotch whisky in both hands and sported imported umbrellas slinging on their shoulders. Soon the canteen staff also arrived but was helpless and terrified as some of the ratings carried arms. As if this was not enough, another batch of ratings brought some steel bars from the closeby smithy shop and dismantled the steel safe from its seat. Efforts were being made to drag the locked safe to nowhere when I left the scene. I then came across some cooks holding fully-loaded automatic weapons in their hands and pointing those towards the direction of Gateway of India where the British destroyers from Trincomalee were expected to arrive. Just then Captain (E) T.N. Kochhar, then an engineer officer of HMIS Narmada, sped past me and told me that the strike committee had broadcast a message that Indian officers would not be harmed if they did not interfere, while Admiral Godfrey required all officers to be in their place of duty and ensure that no violent action or damage to equipment and property took place and that the agitation remained peaceful. In the evening, a news item was received stating that a Gurkha regiment in Karachi had refused to fire at an agitated group of naval ratings. This was day one. The next day morning, the tricolour was hoisted by the ratings on mastheads of most of the ships and establishments. There was a general feeling of anxiety and tension everywhere. The ships deck and lavatories had not been cleaned for past two days. Officers and ratings’ kitchens were out of use. The canteens in every ship were forced open and eatables consumed in lieu of cooked food. The morning news on the radio indicated that fully-armed destroyers of British Navy had already steamed out of Trincomalee harbour and were heading towards Mumbai to quell the Mutiny. The naval ratings’ strike committee decided, in a confused manner, the HMIS Kumaon had to leave Mumbai harbour while HMIS Kathiawar was already in the Arabian Sea under the command of a striking rating. At about 10.30 HIMS Kumaon suddenly let go the shore ropes, without even removing the ships’ gangway while officers were discussing the law and order situation on the outer breakwater jetty. So the wooden gangway, six-metre-long was protruding out of the ship’s starboard waist when the ship moved away from the jetty under command of a revolver bearing senior rating. However, within two hours fresh instructions were received from the strikers’ control room and the ship returned to the same berth. The situation was changing fast and rumours spread that Australian and Canadian armed battalions had been stationed outside the Lion gate and the Gungate to encircle the dockyard where most ships were berthed. Unfortunately, by now all the armouries of the ships and establishments had been seized by the striking ratings. The real danger was that the sophisticated arms with the ammunition were being handled casually by unscrupulous ships clerks, cleaning hands, cooks and wireless operators who had never handled these before. The third day dawned charged with fresh emotions. Sardar Patel’s statement of assurance did improve matters considerably. However, an unruly guncrew of a 25 pounder gun fitted in an old ship, without orders from the strikers, fired a salvo towards the Castle barracks and blew off a large branch of an old banyan tree. It was clear that those bearing arms had started acting on their own without taking orders from their central striking command. The negotiations moved fast, keeping in view the extreme sensitivity of the situation and on the fourth day most of the demands of the strikers were conceded in principle. Immediate steps were taken to improve the quality of food served in the ratings’ kitchen and their living conditions. The national leaders also assured that favourable consideration will be accorded to release of all the prisoners of the Indian National Army. By this time the British destroyers fully armed to go into action arrived and had positioned themselves off the Gateway of Indian Mumbai. Luckily a very grave situation was

tackled in a very timely manner and a real disaster was averted by the

prudent action both by the strikers and the country’s leadership. |

|

|

Line-up of ships of the RIN on the Bombay dockyard breakwater during the mutiny.

. A naval central strike committee was formed on 19 February 1946, led by M. S. Khan and Madan Singh. The next day, ratings from Castle and Fort Barracks in Bombay, joined in the mutiny when rumours (which were untrue) spread that HMIS Talwar's ratings had been fired upon. Ratings left their posts and went around Bombay in lorries, holding aloft flags containing the picture of Subhash Chandra Bose. Several Indian naval officers who opposed the strike and sided with the British were thrown off the ship by ratings. Soon, the mutineers were joined by thousands of disgruntled ratings from Bombay, Karachi, Cochin and Vizag. Communication between the various mutinies was maintained through the wireless communication sets available in HMIS Talwar. Thus, the entire revolt was coordinated.

Freedom on the Waves: The Indian Naval Mutiny, 70 Years Later

‘For the first time the blood of men in the Services and in the streets flowed together in a common cause’ – in remembrance of the Royal Indian Navy’s mutiny, 70 years on

The HMIS Hindustan. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

It is perhaps the natural course of history that some events and individuals are remembered more than others. The Indian struggle for independence is no exception. While the great leaders, and the movements they led command respect, there remain unsung heroes whose contribution has remained unknown except in the scholarly books of historians. The mutiny of the Royal Indian Navy (RIN), which broke out on February 18, 1946 – and, in only five days, delivered a mortal blow to the entire structure of the British Raj – is one oft-forgotten saga. It is worthy of remembrance on its 70th anniversary.

The tide of nationalism after WW2

The Second World War changed geopolitics. It also altered the way societies view the world and themselves. The Indian soldier was no exception. The war had caused rapid expansion of the RIN. In 1945, it was 10 times larger than its size in 1939. Recruitment was no longer confined to martial races; men from different social strata, including many college-educated, enlisted. As the campaigns carried the soldiers across the seas, they saw the world, read the newspapers and learnt that the war was for ‘restoring democracy and freedom’. The Indians themselves were hailed as liberators as they freed Greece, Italy, Burma, Indo-China and Indonesia from Axis rule. This forced many of them to wonder ‘Will not my own country be free? How am I a liberator when my own land is a colony?’ Moreover, the inclusion of Indians in technical posts had proven that they were no less than the whites in professional expertise. And, they had seen first-hand how the Europeans had fled in face of the initial Japanese onslaught – ‘white supremacy’ was an obsolete myth.

But, the end of war also meant demobilization and the anxiety of unemployment. Worse, crude British racism knew no end. British salary was 5-10 times more than that of the Indian. They had better food, better quarters, better quality uniforms and travelled comfortably in individual berths. The Indian barracks were ‘pigsties’, the food was often inedible and Indians were herded into train compartments. The British and Australian troops could use the canteens and messes designated for Indians, but not vice versa. Even medals and recommendations were denied at times. The Indian soldiers loathed the foul language the British used and were not going to tolerate the arrogance anymore. The smoldering resulted in at least 9 minor mutinies between Mar 1942 – April 1945. With the war over, several factories were shut down leading to widespread unemployment. The increasingly strong labor movement protested through more than 1200 strikes during 1945-46.

At the nationalist front, the memories of the heroic ‘Quit India’ movement were fresh. And then, the news of the struggle of Netaji’s INA burst onto the scene. Indians rejoiced that a formal Indian army, led by the charismatic leader, had actually fought the British in battle. As the trial of the INA officers proceeded in the Red Fort, the press printed tales of the non-sectarian character of their struggle. As Nehru described it, ‘[the trials] gave form to the old contest: England vs India…a trial of strength between the will of the Indian people and the will of those who hold power in India’.

The anti-colonial attitude went beyond India. Indians deeply resented the fact that their army was now being sent to crush the new peoples’ governments in Burma, Indonesia and Indo-China, and reestablish French and Dutch colonies. In the last months of 1945, police firing killed 63 protestors at Bombay and Calcutta. These were turbulent times and the young Indian soldier was deeply affected. As BC Dutt, one of the leaders of the RIN mutiny wrote in his memoir, ‘The barrack walls were no longer high enough to contain the tide of nationalism’.

The sparks – the Azad Hindi boys on HMIS Talwar

Based at Bombay, HMIS Talwar was the signal-training establishment of the RIN. With 1500 officers and ratings (enlisted members) on board, it was the second-largest training center in the whole empire. In the informative recollections titled Mutiny of the Innocents and The RIN Strike By a Group of Victimized Ratings, the former mutineers detailed the squalor on board the Talwar and the indifference or racism of the British officers. It was at this time that a colleague returned from Burma secretly carrying letters from INA men addressed to Nehru and Sarat Bose – an incident that ignited their latent patriotism.

Years later, Dutt recalled, ‘…we came from widely different regions… belonged to Hindu, Muslim, Christian and Sikh families. The years spent in the navy had made them – the ratings of the RIN – Indians’. A few of them formed a clandestine group called ‘Azadi Hindi’ and planned to create general disorder and unrest on Talwar. On Navy Day, 1st Dec, 1945, they painted ‘Quit India’, ‘Inquilab Zindabad’ and ‘Revolt Now’ all over the establishment and repeated it when Commander-in-Chief General Auchinlek came on a visit. Dutt was eventually arrested but his defiant reply to Commanding Officer King – ‘…Save your breath, I am ready to face your firing squad’ – made him an instant hero. Another rating, BR Singh, flung his cap down and kicked it in front of the officers.

The unprecedented incidents received press coverage and surprised everyone. However, CO King responded by calling the ratings ‘you sons of bitches’ and ‘sons of bloody junglees’. The emboldened ratings replied with slogans painted all over the Talwar, and even deflated the tyres of King’s car. Though the events were confined to one center, word spread to all the ships and shore establishments in Bombay. Ratings openly began to discuss politics, read nationalist newspapers, set up a INA Relief Fund and submitted individual letters protesting against CO King.

The strike at Talwar ripples outwards

On February 17, when the ratings reiterated their demand for decent food, British officers sneered that ‘beggars cannot be choosers’. This was the last straw. On the 18th morning, 1500 ratings walked out of the mess hall in protest, a clear act of mutiny. Yet they also declared that ‘this is not a mere food riot. [We] are about to create history…a heritage of pride for free India.’ By 4.30pm, the ratings had rejected the appeals of their officers and even Rear Admiral Rattray. The ‘strike committee’ decided their task was to take over the RIN and place it in the command of national leaders. A formal list of demands called for release of all Indian political prisoners including INA POWs and naval detainees, withdrawal of Indian troops from Indonesia and Egypt, equal status of pay and allowances and best class of Indian food. It also formally asked the British to quit India.

The Bombay press was puzzled by the turn of events. Only the Free Press Journal understood the significance of what was underway, and editor S. Natarajan even offered his columns to the ratings. By that night, AIR and BBC had to broadcast the news of the RIN strike and it spread like wildfire across the country.

The next morning, sixty RIN ships harboured at Bombay – including the flagship HMIS Narbada, HMIS Madras, Sind, Mahratta, Teer, Dhanush, Khyber, Clive, Punjab, Gondawana, Berar, Moti, Jamna, Kumaon, Oudh – and eleven shore establishments, including the large Castle Barracks and Fort Barracks, pulled down the Union Jack and hoisted the three flags of the Congress, the Muslim League and the Communist Party. Under the ‘joint banner’ of Charka-Crescent-Hammer and Sickle, the ratings marched in thousands towards the epicenter, the Talwar. They chased foreigners, stoned British-owned shops and pulled down the flag from the USIS library. By the morning of February 20, the strike had spread to Calcutta, Karachi, Madras, Jamnagar, Vishakapatnam, Cochin and other navy stations.

In all, around eighty ships, four flotillas, twenty shore establishments and more than 20,000 ratings joined the mutiny. Most Indian officers, barring a few like Lieutenant Sobani and Lieutenant Mani, stayed away. Yet in 48 hours, British India had lost control of its navy.

The Indian National Navy

A newly-formed Naval Central Strike Committee (NCSC) included 12-36 representatives from all the ships and barracks of Bombay. Leading signalman MS Khan and petty officer telegraphist Madan Singh were elected president and vice-president. Years later, their comrades recalled how both were ‘free of the communal virus’. They declared the RIN renamed as the ‘Indian National Navy’. They also decided that their struggle would be a non-violent one and henceforth they would take orders ‘only from the national leaders’.

As the NCSC asked for guidance, however, what they heard was an uneasy silence. Finally, the Left-leaning Congress leader Aruna Asaf Ali advised them to accept the counsel of Sardar Patel. She also informed Nehru, explaining the tense situation that was ‘climaxing to a grim close’. Meanwhile, the ratings marched in discipline at Colaba and Flora Fountain, with slogans of ‘Hindu Muslim ek ho’ and ‘Inquilab Zindabad’. The people of Bombay cheered them. Journalists who visited the Talwar were surprised to find that the primary demand of the ratings was now not better amenities, but freedom from British rule. They even rebuked the journalist of the Times of India for having tried to malign them in the previous day’s reporting. The ratings told the reporters, ‘We shall use the little knowledge they have given us against them. Remember the INA. We too shall teach them a lesson’.

The government had been stunned, but now, deducing that nationalist leaders were not keen to support the uprising, Admiral Godfrey reached Bombay to negotiate with the NCSC. The political inexperience of the young NCSC made them hesitate, and they accepted Godfrey’s demand that they return to their respective ships and barracks. Within an hour, Godfrey had sent the army to surround the barracks. Realizing they had been tricked, the ratings discontinued their hunger-strike, broke open the magazine and prepared for battle.

Battle at Castle Barracks; India’s ‘Battleship Potemkin’ moment

The next morning, the British officers discovered that the Maratha soldiers ordered to attack the barracks, were sympathetic to the ratings. They were replaced with British troops and rating Krishnan became the first martyr of the counter-offensive. In face of spirited resistance, the attacks against both Castle Barracks and the ships were indecisive. That night, a press release from NCSC read, ‘ten ratings and around fifteen British soldiers have been killed’. Prime Minister Attlee, however, had announced that seven ships were heading for Bombay and Admiral Godfrey had demanded unconditional surrender. Realizing the danger, the NCSC earnestly appealed ‘You, our people and our respected political leaders come to our aid…you must support us.’

The leaders were still absent, but the people had come in overwhelming numbers. A rumour that the British were going to starve the ratings into surrender, brought thousands of civilians to the Gateway of India with fruits, milk, bread and vegetables. The ratings came by motorboats and collected all that was offered. Hindu, Muslim and even Iranian shops and eateries asked them to take whatever they needed for free – similar to the famous fraternizing scenes of the classic Battleship Potemkin – and the Indian soldiers on duty did not stop them.

The ‘hartal’ – bloodbath at Bombay and the battle at Karachi

The Bombay Students’ Union and the CPI had called for a general strike and the NCSC had asked people to make it a success. In contrast, Gandhi was clearly unsupportive of the unplanned uprising and Sardar Patel even asked people to ‘go about their work as usual’. For once, the people rejected the great leaders. The strike was ‘total’ and processions rolled across the city. At the seaside, British troops now prevented any food from reaching the ships. In the Fort area, a military truck recklessly ran over couple of protestors. This triggered a general mayhem and, within few hours, at least eleven military trucks were torched. The army responded with indiscriminate firing, especially in working class areas of Parel. By night, the city was under curfew.

At Karachi harbor, HMIS Hindustan had resisted British small-arms throughout the February 21. They had been helped by the once-loyal Gurkha and Baluch regiments, who had refused to fire at them. By the next morning, however, the British had positioned artillery around the ship, and as the tide ebbed, the Hindustan’s levels dropped and made it difficult for the ratings to aim their guns. The artillery opened fire. After thirty minutes, with six ratings dead, the ship surrendered. HMIS Kathiawad, which was in high seas, had responded to the distress calls from Hindustan. However, learning that they would be too late for Karachi, they turned towards Bombay.

Surrender

With no assistance from either the Congress or the League, the NCSC were disheartened. A show of strength by RIAF bombers had only been delayed because an entire squadron from Jodhpur, piloted by Indians, had mysteriously developed engine trouble. Instead a British squadron flew over the ships. Clearly, Admiral Godfrey had firepower at his disposal and he would use it.

Khan, Singh and their colleagues met under the shadow of the slaughter in the city. They agreed that ‘the debt of this blood has to be repaid a hundred-fold’ and made order against any unconditional surrender. Hectic negotiations with Sardar Patel followed. He assured them that the national leadership would look into their grievances and prevent any victimization. A clear divide formed among the ratings – many wanted to fight along with the people, but others cautioned that their military resources were very limited. Besides, having declared that their objective was to do as instructed by the national leaders, how could they go against the same leadership?

At that moment, Jinnah’s message reached the NCSC; he also asked them, especially the Muslim ratings, to surrender. This sealed the fate of the mutiny – thirty out of 36 members of NCSC now voted to stop the struggle.

From private correspondence, it seems Patel’s decision had been influenced by the idea that ‘discipline in the army cannot be tampered with’. A few months later, Patel would refer to the ratings as ‘a bunch of young hotheads messing with things they had no business in.’

Nehru would accept that ‘the gulf that separated the people from the armed forces had once for all been bridged. The janata and soldier have come very close to each other.’ But both leaders had failed to provide the ratings with the political support they needed; and, when hundreds of ratings were imprisoned for months in abominable conditions at the Mulund camp, there would be no one to speak for them. The CPI fared better. Its call for nation-wide strikes clearly demonstrated the solidarity of the people with the ratings. But, their overall alignment with the national movement finally let the RIN mutiny down.

On February 23, at 6am, all ships surrendered. At the Thane-based HMIS Akbar, 3500 ratings and 300 sepoys refused to surrender, but had to capitulate in face of bayonets. When HMIS Kathiawad reached the Bombay coast, it found the royal cruiser Glasgow blocking its way. In a last act of valiant defiance, the little corvette threateningly aimed its puny 12-pounder gun at the giant adversary. ‘Goliath’ Glasgow, perhaps in respect for bravery, allowed them to sail into Bombay harbour – the first Indian-administered ship to ever reach an Indian port to assist Indians. They arrived to the news that it was all over.

The battles rage on

The general public was, however, in no mood to give up. Seething with anger, over the next day, the city raised barricades and fought bullets with stones. In just two days, the official tally recorded 228 civilians and three policemen dead, and 1,046 people and 91 policemen and soldiers injured. By the evening of February 23, Congress, League and CPI volunteers were asking people to disperse. In Calcutta, the strike led by the Union of Tramway Workers extended into the next day and, for the first time, railway workers joined in, paralysing large parts of the country. Notably, at Majerhat in Calcutta, jawans and NCOs of the 1386 Indian Pioneer Company joined the strike. When their angry commanding officer slapped Naik Budhan Sahab, he was slapped back. At his court-martial, a defiant Budhan thundered, ‘What? I should beg of mercy from my enemy?’ – sending shockwaves throughout the military establishment.

In its last statement released on the night of 22nd February, the NCSC concluded, ‘Our strike has been a historic event in the life of our nation. For the first time the blood of men in the Services and in the streets flowed together in a common cause. We in the Services will never forget this. We know also that you, our brothers and sisters, will not forget. Long live our great people. Jai Hind’.

In conjunction with the INA trials and the peasant movements of Telengana and Tebhaga, the peoples’ unity during the mutiny had loosened the last pillars of the Raj. Indian leaders may have fumbled, but the British knew that their days were over. On March 15, Prime Minister Attlee accepted that, ‘The tide of nationalism is running very fast in India and indeed all over Asia…the national ideas have spread … among some of the soldiers.’ Historians agree that the one thing the British had consistently feared was united mass movements. They would not risk facing another ‘Quit India’, this time with veterans of the INA and RIN in the country. A year later, they fled before the Empire collapsed on their own heads.

Anirban Mitra is a molecular biologist and a teacher residing in Kolkata.

=============================================

Home > Archives (2006 on) > 2016 > Role of Karachi in the 1946 Naval Rebellion

Mainstream, VOL LIV No 11 New Delhi March 5, 2016

Role of Karachi in the 1946 Naval Rebellion

Wednesday 9 March 2016

by Aslam Khwaja

The following is a paper presented by the author at an international conference on Karachi at Karachi in November 2015. February 2016 marked the seventieth anniversary of the Royal India Navy’s Mutiny.

The Royal Indian Navy’s Mutiny was a total strike and subsequent revolt by the Indian sailors of the Royal Indian Navy on board ship and shore establishments at Mumbai harbour on February 18, 1946. Though the initial flashpoint was in Bombay, the revolt spread in a matter of hours throughout British India, from Karachi to Kolkata. It involved 78 ships, 20 shore establishments and 20,000 sailors. The strike found support amongst the Indian population, though it was condemned by the Congress and Muslim League. Only the Communist Party of India supported it.

The Royal Indian Navy’s Mutiny, often wrongly called the Bombay Mutiny, was repressed with force by the British Royal Navy leaving seven dead and thirtythree wounded. The strikers gave way on getting no support from the Congress and Muslim League. Despite assurances by the Congress and Muslim League of no victimisation, widespread arrests were made followed by court martials and large-scale dismissals from the service. None of those dismissed was reinstated into either the Indian or Pakistani navies after independence.

The Bengali community residing in Karachi used to celebrate Durga Puja on the lawns of Mama Parsi Girls School. During the Puja celebrations of 1945-46, the Indian Naval ratings (a number of them had been members of the All India Students Federation during their student life) posted in Karachi contacted the puja committee to allot them some time for a variety programme. A slot and time was readily allotted to them. This programme was held on Saptami, the second day of the puja.

At that time, there were five shore establish-ments in Karachi, namely, H.M.I.S. Monze-Local Naval Defence Base, H.M.I.S. Himalaya-Gunnery School, H.M.I.S. Bahadur-Boys’ Training School, H.M.I.S. Dilawar-Boys’ Training School, and H.M.I.S. Chamak-Radar Training School. All these establishments were situated in an island called Manora. At the far south of Karachi city was the Keamari Jetty. Manora was separated from the city by a small inlet of the Arabian Sea.

The first resentment among the Indian ratings surfaced during August 1945, when their application to hold a cultural programme on August 7 to commemorate the death anniversary of Tagore was rejected by the Commanding Officer. They were however allowed to pay their respects to him in their class room.

On the first Sunday after the Durga Puja, the Indian ratings assembled at the beach and formed the Sailors Association, Manora. Their first task was to raise funds for the INA Relief Fund, but they never intended any sort of mutiny, as the island was separated from the mainland and sufficient arms were not available to sustain such a mutiny.

The news of the Bombay Mutiny reached the Naval establishments and Karachi city on the morning of February 19 through newspapers and was received with tremendous excitement and suppressed jubilation at both places. Group discussions in whispers started among ratings about the course they should take. At lunch-break the Sailors Association members of Chamak gathered and decided to hold a meeting of all establishments at the sea beach in the late evening.

At the meeting all participants agreed to join the mutiny but there was no unanimity at the beginning. After long discussions consensus developed for February 21, following which a six-point programme was chalked out; it read:

1. To assemble at Keamari Jetty at 10.00 am.

2. To take out a procession through the streets of Karachi in support of the Bombay ratings.

3. To invite the Dock workers of the Keamari Jetty to join in the procession.

4. Raise slogans denouncing the British Imperia-lists and urge the Congress and Muslim League to unite.

5. Complete abstention from work.

6. The ratings of Bahadur to march over at Chamak and ratings of these two establishments to proceed jointly to Keamari.

Ten ratings were selected to represent their respective establishments. It was decided that work should be carried out as silently as possible. After deciding to assemble on the same spot again on February 20 at 8.00 pm, the participants dispersed.

The day of February 20 broke without a pipe call to wake up the ratings. The morning papers, particularly the Sind Observer, carried the news of the dramatic turn the Bombay Mutiny was taking. At this moment the Commanding Officer broke the news of the Bombay uprising officially to the ratings and warned of the consequences for following suit. Meanwhile, the ratings of Hindustan were ordered to leave Karachi on the morning of February 21 and by lunch-time they drove away all the officers, both British and Indian, from their ship and took full control of the ship themselves. Thus Hindustan got the distinction of heralding the mutiny in Karachi. In their evening meeting, members of the Indian Association finalised next day’s programme and decided to write eight slogans in Hindi and Urdu on the city walls and placards they would carry. These slogans were:

1. Ratings of Himalaya—Unite

2. Ratings of Chamak—Unite

3. Ratings of Bahadur—Unite

4. Hindustan Zindabad

5. Down with British Imperialism

6. Give blood to get freedom

7. We shall live as a free nation

8. Tyrants, your days are over.

It was decided that the ratings of Himalaya would proceed from their own jetty while the ratings of Chamak and Bahadur would proceed from the Manora Jetty. The ratings of Himalaya should have with them the ratings of Hindustan and Travancore and all would assemble just outside the Jetty at about 10.30 am. It was also decided that a complete hunger strike will be observed in solidarity with the rebels of Bombay.

As the night was over, the morning sky was filled with the slogans of hundreds of vigorous youthful voices. The R.I.N. ratings in Manora had rebelled. The Commanding Officer started frighte-ning the ratings by saying that the military had been deployed at Keamari Jetty with shoot to kill orders. The marching ratings were greeted with clapping by the residents of inhabitants of Manora island, most of them fisherfolk or boat vendors. To show their solidarity with the rebels, the local boatmen refused to charge the fare from the ratings to ferry them to the Jetty.

During this commuting process, some British troops riding on a motor boat opened fire on the ratings of Hindustan, killing two of them on the spot and wounding a few others. Other ratings of Hindustan, still at their establishment, fired back to the British troops with twelve pounders and forced the enemy to retreat.

As the Dock Labour Union members heard the sound of firing, they rushed to the Communist Party of India and All India Trade Union Congress offices situated at the Light House area of Bundar Road, where Comrades Sobho Gianchandani, A.K. Hangal (later IPTA Chairman and veteran actor), Ainshi Vidyarthi and other comrades were busy with their routine work.

Comrade Sobho immediately left the office and walked to the Native Jetty Bridge. On the way he met people who curiously asked him about the details of the firing and the number of casualties from either side.

As the CPI’s Sindh Secretary Comrade Jamaludin Bukhari was in Bombay, so Comrade Sobho was the virtual leader of the party in Sindh; after consultation with progressive Sindhi fiction writer Gobind Malhi and I.K. Gujral (later Prime Minister of India), Sobho called for a public meeting in the evening at the Eidgah Maidan ground, and for the mobilisation of workers from different factories and localities. In the late afternoon, Asif Karvani informed the Karachi comrades that CPI leader Comrade S. A. Dange had given a general strike call for next day.

At 6 in the evening the public meeting started with five chairs on the stage, with about four hundred participants and more than half of them were students. The meeting started with Comrade Relaram Lilaram reciting an Urdu poem, ‘Chhute aseer to badla hua zamana tha’ [when the imprisoned were relased, the times had changed], followed by Sheikh Ayaz’s Sindhi poem, ‘Ghai inqilab...Ghai inqilab’.

As the meeting, chaired by Professor Karvani, progressed, workers from different factories also joined in solidarity and the number of participants soared to eight thousand. Comrades Sobho, A.K. Hangal and Professor Karvani in their speeches paid rich tributes to the Naval rebels and appealed for next day’s general strike. During the meeting Qazi Mohammed Mujtaba, the provincial President of the All India Trade Union Congress, who was seriously ill, reached the venue and gave the concluding speech.

Although the active workers decided to spend the following night at different places to avoid expected arrests, the local police with the help of the C.I.D. conducted late night raids at different places and arrested Sobho, Hangal and Karvani and kept them at the Saddar Police Station lock-up.

Next morning Karachi responded with a complete shut-down, while Comrade Ainshi and Gobind Malhi established the protest headquarter at Eid Gah Maidan by hoisting the flags of the CPI, INC and ML. At about ten, workers of the West Wharf, under the leadership of Gulab Bhagwani, and the workers of dockyard, trams, buses and different factories under their respective union leaders began reaching at Eid Gah Maidan, where the police and military failed to stop the people pouring from Saeed Manzil to Dow Medical College and D.J. College to Ranchore Lane.

As the people refused to disperse despite the warnings by the police and military, the administration brought in the Sindh Assembly member, Swami Kirshna, and Congress leader Doctor Tarachand in a police vehicle but people instead of dispersing on their appeal, asked them to join the protest. Thereafter the Muslim League leader, Mahmood Haroon, was also brought there in a police vehicle but he too got the same response.

As the situation came to a boil, on the request of Sindh Chief Minister Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah, the founder of modern Karachi Jamshed Mehta arrived to appeal for dispersal but for the first time citizens of Karachi refused to listen to Mehta and the police was forced to take him away from the hostile mob.

Meanwhile the police attacked the protest camp and arrested Malhi, Ainshi and Gulab and tried to remove the flags which antagonised the people who started throwing stones at the police. Initially the police fired teargas shells but later opened firing on the people. Women threw wet clothes from the windows and galleries of their houses to the people to lessen the impact of the teargas. At some places they threw chilies and boiling water on the police.

Over a dozen citizens were martyred and dozens injured in the police firing that continued for over one hour. The first civilian martyr of that day was the young son of a local trader, Hassan Ali Soda Waterwala. The arrested comrades, kept in the police lock-up, got to know about the police action of the day through police wireless relays, according to which clashes between the masses and police continued till 6.00 in the evening.

On the other hand, the British troops took the dead bodies of the fallen comrades and injured to Hindustan, and they were followed by three to four hundred ratings of Himalaya in a procession. The rest of the ratings, after reaching Himalaya, started consultations about their future course. Meanwhile, as the ratings started raising slogans, the dock workers also shouted slogans with equal vehemence. For over two hours, the ratings and dock workers raised slogans in front of the pointed guns of the British troops. During that time many city journalists reached the spot and a reporter of daily Sind Observer informed the ratings that the access to Hindustan had been blocked and so the exact figure of the dead and injured could not be known.

At 6.30 the ratings started their open meeting, which decided that they will initiate indefinite hunger strike if the British troops were not called back. They also decided to reassemble between 9.30 to 10.00 the following morning at the Jetty. The meeting decided for relay slogans at nine at the night, which was implemented. Late at night, the British command issued an ultimatum to the Indian ratings that if they did not end their mutiny by 10 in the morning, their ships would be directly bombed.

In the morning of February 22 all the ratings of Chamak assembled at the Parade Ground at 8.30 ready to march towards Manora Jetty when they saw the ratings of Himalaya running towards them. The British soldiers had scared away all the boatmen threatening to kill anybody who would come within a mile of Hindustan.

In the morning all the officers of Chamak, visited the striking ratings and the Commanding Officer in his brief address announced that if the protesters follow the discipline, the British troops would be removed.

Later he allowed representatives of the ratings to join in the last rituals of the martyred ratings, for which the bodies of seven Hindu, four Muslim and three Sikh ratings were brought to the other end of the city. The faces of the martyrs were not shown to their comrades.

Consequently, active leaders of the Sailors Association were arrested and three of them, namely, Anil Roy, Harilal from Ajmer and Akbar Ali from Punjab, were ordered to be tried by Court Martial. Not one of them was sentenced and in the second week of June, the orders for Court Martial were withdrawn.

The Karachi-based arrested Communist workers Sobho Gianchandani, A. K. Hangal and Professor Karvani were also released after a couple of weeks.

Victims of police firing on a crowd that had demonstrated in support of the mutiny.

On 19 February, the Tricolour

was hoisted by the ratings on most of the ships and establishments. By 20 February, the third day, armed British destroyers had positioned themselves off the Gateway of India. The RIN Mutiny had become a serious crisis for the British government. An alarmed Clement Attlee,

the British Prime Minister, ordered the Royal Navy to put down the revolt. Admiral J.H. Godfrey, the Flag Officer commanding the RIN, went on air with his order to "Submit or perish". The movement had, by this time, inspired by the patriotic fervour sweeping the country, started taking a political turn.

The naval ratings’ strike committee decided, in a confused manner, that the HMIS Kumaon

| HMIS Kumaon |

had to leave Bombay harbour while HMIS Kathiawar was already in the Arabian Sea under the control of mutineering ratings. At about 1030 Kumaon suddenly let go the shore ropes, without even removing the ships’ gangway while officers were discussing the law and order situation on the outer breakwater jetty. However, within two hours fresh instructions were received from the strikers’ control room and the ship returned to the same berth.

The situation was changing fast and rumours spread that Australian and Canadian armed battalions had been stationed outside the Lion gate and the Gungate to encircle the dockyard where most ships were berthed. However, by this time, all the armouries of the ships and establishments had been seized by the striking ratings. The clerks, cleaning hands, cooks and wireless operators of the striking ship armed themselves with whatever weapon was available to resist the British Destroyers that had sailed from Trincomalee in Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

The third day dawned charged with fresh emotions. The Royal Air Force flew a squadron of bombers low over Bombay harbour in a show of force, as Admiral Rattray, Flag Officer, Bombay, RIN,{Admiral Sir Arthur Rullion Rattray (1891–10 August 1966)} issued an ultimatum asking the ratings to raise black flags and surrender unconditionally.

In Karachi, by this time, realising that little hope or trust could be put on the Indian troops, the 2nd Battalion of the Black Watch had been called from their barracks. The first priority was to deal with the mutiny on Manora Island.

The decision was made to confront the Indian naval ratings on board the destroyer Hindustan, armed with 4-in. guns. During the morning three guns (caliber unknown) from the Royal Artillery C. Troop arrived on the island. The Royal Artillery positioned the battery within point blank range of the Hindustan on the dockside. An ultimatum was delivered to the mutineers aboard Hindustan, stating that if they did not the leave the ship and put down their weapons by 10:30 they would have to face the consequences. The deadline came and went and there was no message from the ship or any movement. Orders were given to open fire at 10:33. The gunners' first round was on target. On board the Hindustan the Indian naval ratings began to return gunfire and several shells whistled over the Royal Artillery guns. Most of the shells fired by the Indian ratings went harmlessly overhead and fell on Karachi itself. They had not been primed so there were no casualties. However, the mutineers could not hold on. At 10:51 the white flag was raised. British naval personnel boarded the ship to remove casualties and the remainder of the mutinous crew. Extensive damage had been done to Hindustan's superstructure and there were many casualties among the Indian sailors.

HMIS Bahadur was still under the control of mutineers. Several Indian naval officers who had attempted or argued in favour of putting down the mutiny were thrown off the ship by ratings. The 2nd Battalion was ordered to storm the Bahadur and then proceed to storm the shore establishments on Manora island. By the evening D company was in possession of the A A school and Chamak, B company had taken the Himalaya, while the rest of the Battalion had secured Bahadur. The mutiny in Karachi had been put down.

In Bombay, the guncrew of a 25-pounder gun fitted in an old ship had by the end of the day fired salvos towards the Castle barracks. Patel had been negotiating ferevently, and his assurances did improve matters considerably However, it was clear that the mutiny was fast developing into a spontaneous movement with its own momentum. By this time the British destroyers from Trincomalee had positioned themselves off the Gateway of India. The negotiations moved fast, keeping in view the extreme sensitivity of the situation and on the fourth day most of the demands of the strikers were conceded in principle.

Immediate steps were taken to improve the quality of food served in the ratings’ kitchen and their living conditions. The national leaders also assured that favourable consideration would be accorded to the release of all the prisoners of the Indian National Army. A very grave situation was tackled in a very timely manner and a real disaster was averted by the prudent action both by the strikers and the country’s leadership.

The mutiny caused a great deal of panic in the British Government. The connections of this mutiny with the popular perceptions and changing attitudes with the activities of the INA and Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose was taken note of and its resemblance of the revolt of 1857 also caused alarm among the British administration of the time. The fact that the mutiny of 1857 sparked off from a seemingly trivial and unexpected issue of greased cartridges, and that later historical analysis had revealed deep seated resentment among the then subjects of the East India Company led to fears that an identical situation was developing in India.

18 February 1946 – The Unknown Indian Naval Mutiny

That the Naval Mutiny was short-lived and has become virtually an unknown episode in the post-Independence era is a crying shame. It is, nonetheless, a remarkable story; one that deserves a more prominent place in British-India history, writes Pramod Kapoor, as he walks us through the brief but fierce event

A few years after India’s independence, Britain’s former Prime Minister Clement Atlee was in Calcutta on a semi-official visit. During a banquet at the Governor’s House, Justice PV Chakraborty, former chief justice of the Calcutta High Court, leaned across and asked Atlee how much impact Mahatma Gandhi’s Quit India movement had on hastening Britain’s exit from India. Atlee’s answer was “minimal”, adding that it was the unrest in the Indian defence forces, particularly the mutiny by naval ratings, that forced them into leaving India earlier than planned.

For most Indians, that reference would be confusing. The mutiny they know about and recorded in the history books happened in 1857, and was called the Sepoy Mutiny. The one Atlee referred to took place in February, 1946, in Bombay, and is a largely ignored and unknown event, despite it being so serious in terms of the security threat it posed. It involved 2,000 Indian naval personnel, the loss of some 300 civilians lives, and seizing of armories on British ships with their guns trained on iconic structures such as the Gateway of India, the Taj Hotel and the Yacht Club. Now, at the end of its 70th anniversary, it needs to be resurrected and remembered for the incredible bravery and defiance shown by the ratings, all young men between 17-24 years old, who dared to face the might of the British Empire and played a major role in the British advancing the date for the transfer of power.

Few will believe that for an incredible five days, these ratings (enlisted members of a country’s navy), took over the naval ships moored in Bombay harbor, took down the British flags and replaced them with Indian flags, and had the British Empire in a panic, with flurries of telegrams to Whitehall, furious debates in the House of Commons and House of Lords, panicky requests for reinforcements and battle ships ordered to sail to Bombay from nearby ports. Inspired by the heroism of the ratings, Bombay’s citizens poured out onto the streets in support, burning and looting British-owned shops.

The saga began on Navy Day, December 1, 1945, when a group of ratings belonging to HMIS Talwar a shore establishment (now Badhwar Park) in the naval dockyard area in Bombay, decided to test their resolve and commitment to challenge the British naval forces in India. They were inspired by the charged political atmosphere and, in particular, disturbing reports from the INA trials taking place at Delhi’s Red Fort. The initial group, calling themselves Azad Hindi’, consisted of around 20 ratings and the first phase of their plan was to strike work. They were enough reasons to do so, starting with the humiliating mass demobilisation of Indian naval personnel after World War II, despite the heroism and sacrifice they had displayed while fighting alongside British and Allied forces. There was also the supercilious treatment by British officers, discrimination against Indians in living conditions, and the poor quality of food they were served on a regular basis.

December 1, 1945, was the ideal day to literally test the waters. It was to be the first time in the history of the Royal Indian Navy that civilians had been invited to board the naval ships and shore establishments to witness the pomp and ceremony. The minute preparation for the ceremony was over and the British officers left, the Azad Hindis got busy. The next morning, HMIS Talwar the shore establishment in Colaba Bombay, was littered with torn flags and slogans like ‘Quit India,’ ‘Down with the Imperialists’ and even ‘Kill the British’, were painted in large type on the walls of the barracks. The British were enraged but made no arrests due to lack of evidence.

But who were these brave men? One was Telegraphist RK Singh, who was inspired by Subhash Chandra Bose but believed in the Gandhian principle of open defiance and was the first to submit his resignation as a mark of protest. In the defence forces, a soldier can be dismissed, relieved or given premature retirement. Singh insisted on resigning. He was summoned to the office of the Flag Officer Bombay (FOB). There, he argued with his seniors, threw his Royal Indian Navy (RIN) cap on the floor and kicked it as a mark of disrespect to the crown and the British Raj. It was the ultimate crime. He was immediately arrested and sent to Arthur Road jail in Bombay. His name was promptly removed from navy rosters. Neither does he find mention in the history of the freedom movement in India, even though his act of defiance was no less than any freedom fighter.

His action inspired Lead Telegraphist Balai Chandra Dutt, 22, who had left the comfort of a Bhadralok family in Bengal to join the navy. Dutt would play a leading role in the events of February 1946, which was when the ratings staged their mutiny. On February 2, the visit of Flag Officer Commanding, Royal Indian Navy, or FOCRIN, was announced. He was scheduled to visit HMIS Talwar, the second biggest signal school for the navy across the British Empire. Despite the extra security, BC Dutt who was on duty from 2-5 am, managed to write seditious slogans like ‘Quit India’ and ‘Jai Hind’ and paste pamphlets below the dais erected for the occasion. He was caught with a bottle of gum and chalk, and seditious literature was found in his locker. He also was arrested, but his action made him a hero to the 20,000 ratings who joined in the uprising that would rattle the British Empire.

On the night of February 6/7, Azad Hindis deflated the tires of the car belonging to their commanding officer FW King, and scrawled the same slogans on the paintwork. Commander King flew into a rage on seeing his car and stormed into the barracks. Defying naval custom, none of the ratings stood up or saluted. Seeing this, he shouted, ‘Get up you sons of coolies, you sons of Indian b***hes, Sons of bloody junglees’. It was the last straw. From now, the mini-revolt would gather steam and become a full scale uprising or a mutiny in military terms. On the morning of February 18, Azad Hindis joined by a large group of ratings on HMIS Talwar, refused food and declared a hunger strike. Being telegraphists, they relayed the news immediately. Within no time, the news of their defiance reached all ship and shore establishments around the major ports of Bombay, Karachi, Vishakhapatnam, Madras, Calcutta, Thane, and as distant as Bahrain, Singapore and Indonesia.

Eventually, the uprising would involve 20,000 ratings, 78 ships and 20 shore establishments. The British were taken by surprise and before they realised the extent of the mutiny, the brave young sailors had taken control of the armoury on most ships and establishments, forced the officers to beat a hasty retreat, pulled down the British flags from all the ships and replaced them with flags of the Indian National Congress, Muslim League and Communist Party of India. Having gained control of the ships, they pointed the ship’s guns at the Yacht Club, Gateway of India and the Taj Mahal hotel, buildings that signified the pride of Britain in India. They used this as collateral against any possible use of retaliatory force by the British.

In the course of a few days, they had the British authorities on the run. For an entire week, Bombay resembled a city at war. Hundreds of civilians joined in, leading to widespread loot, arson and even deaths. Mill workers united with railway workers to bring the city to a grinding halt. The British rushed in troops and additional forces with mixed results. Asked to open fire on the mutineers, soldiers of the Maratha brigade refused. The British used other forces to fire on the ratings, and it led to close to 300 deaths. This was now a full-fledged mutiny, and inevitably, political intervention would be required.

The politicians were divided on the issue. The Communists supported the mutiny. Independence activist Aruna Asaf Ali addressed the ratings and pledged support. The Congress saw some disagreement on the issue between Jawaharlal Nehru and Sardar Patel. Nehru initially supported the mutiny and arrived in Bombay against Patel’s wishes and met the ratings. On the other hand, the Muslim League, under MA Jinnah, appealed to Muslim ratings to abandon their strike. Gandhi was totally opposed to the mutiny and put Patel in charge of sorting out the issue.

It was hotly debated in the council house (Parliament) in Delhi and the tremors reached Westminster in London. There were angry exchange of telegrams between offices of Prime Minister Attlee and the Viceroy of India Lord Wavell. The British government ordered seven ships including HMS Glasgow, its most powerful warship in the Indian Ocean to sail full steam from Trincomalee in Ceylon to Bombay to crush the mutiny. Admiral Godfrey, head of naval forces in India, threatened to destroy the Royal Indian Navy. The Royal Air Force made threatening sorties over the Bombay harbour.

On Gandhi’s advice, Patel invited the newly formed Naval Strike committee lead by senior Telegraphists, MS Khan and Madan Singh, for discussion. Talks went on for several hours and Patel assured them that there would be no victimisation. The Strike committee met with the ratings to discuss the terms. All night they argued, disagreed and shouted at each other and eventually wept like children.

At 6am on February 23, the senior ratings carried white flags to their respective ships as a signal of surrender. Many had tears in their eyes, yet they held their heads up high. They had composed a surrender document the last few lines of which read: “Our strike has been a historic event in the life of the nation. For the first time, the blood of the men in services and the people flowed together in a common cause. We have not surrendered to the British. We have surrendered to our own people. We in services will never forget this…” The surrender document was said to be drafted by Mohan Kumarmangalam, the Communist leader.

The denouement was tragic and a blatant betrayal of the promises made by the politicians. Almost 1,000 ratings were arrested and sent to various camps, a few were given jail terms, majority were escorted to railway stations, handed a one-way ticket home for good. About the mutiny, Gandhi said: “…they (ratings) were thoughtless if they believed that by their might they would deliver India from foreign domination.” BC Dutt, the hero of the uprising, later wrote a book on the subject. In the last chapter, he wrote: “The aftermath of a revolution is determined by the enormity of the change affected by it. The Indian revolution is itself an example, for despite the presence and influence of Mahatma Gandhi, blood did spill.”

Surprisingly for events of the magnitude and reach that the mutinies came to be, the mutineers in the armed forces got no support from the national leaders and was largely leaderless. Mahatma Gandhi, in fact, condemned the riots and the ratings’ mutiny, his statement on 3 March 1946 criticised the strikers for mutinying without the call of a "prepared revolutionary party" and without the "guidance and intervention" of "political leaders of their choice". He further criticised the local Indian National Congress leader Aruna Asaf Ali, who was one of the few prominent political leaders of the time to offer her support for the mutineers, stating she would rather unite Hindus and Muslims on the barricades than on the constitutional front. Gandhi's criticism also belies the submissions to the looming reality of Partition of India, having stated "If the union at the barricade is honest then there must be union also at the constitutional front" The Muslim League issued similar statements which essentially argued that the unrest of the sailors was not best expressed on the streets, however serious the grievance may be. Legitimacy could only, probably, be conferred by a recognised political leadership as the head of any kind of movement. Spontaneous and unregulated upsurges, as the RIN strikers were viewed, could only disrupt and, at worst, destroy consensus at the political level. This may be Gandhi's (and the Congress's) conclusions from the Quit India Movement in 1942 when central control quickly dissolved under the impact of British repression, and localised actions, including widespread acts of sabotage, continued well into 1943. It may have been the conclusion that the rapid emergence of militant mass demonstrations in support of the sailors would erode central political authority if and when transfer of power occurred. The Muslim League had observed passive support for the "Quit India" campaign among its supporters and, devoid of communal clashes despite the fact that it was opposed by the then collaborationist Muslim League. It is possible that the League also realised the likelihood of a destabilised authority as and when power was transferred. This certainly is reflected on the opinion of the sailors who participated in the strike It has been concluded by later historians that the discomfiture of the Mainstream political parties was because the public outpourings indicated their weakening hold over the masses at a time when they could show no success in reaching agreement with the British Indian government.

Naval Uprising Statue, Colaba

The only political party to give unconditional support to the revolt was the Bolshevik-Leninist Party of India, Ceylon and Burma (BLPI). As soon as it got news of the revolt it came out with a call for a Hartal in support of the mutineers. BLPI members Prabhakar More and Lakshman Jadhav led the textile workers out on strike. Barricades were set up and held for three days. However, attempts to contact the mutineers were foiled by British troops.

Possibly the only major political segment that still mentions the mutiny it is the Communist Party of India. The literature of the communist party, certainly see the RIN Mutiny as a spontaneous nationalist uprising that was one of the few episodes at the time that had the potential to prevent the partition of India, and one that was essentially betrayed by the leaders of the nationalist movement However, at the time, the CPI attempted to diffuse the situation, co-operating with the Congress and the Muslim League in trying to keep the peace.

More recently, the RIN Mutiny has been renamed the Naval Uprising and the mutineers honoured for the part they played in India's Freedom. In addition to the statue which stands in Mumbai opposite the sprawling Taj Wellingdon Mews, two prominent mutineers, Madan Singh and B.C Dutt, have each had ships named after them by the Indian Navy.

Legacy and assessments of the effects of the Mutiny

The most significant factor of this mutiny, with hind-sight, came to be that Hindus and Muslims united to resist the British, even at a time that saw the peak of the movement for Pakistan. This critical assessment starts from events at the time of the mutiny. The mutiny came to receive widespread militant support, even for the short period that it lasted, not only in Bombay, but also in Karachi and Calcutta on 23 February, in Ahmedabad, Madras and Trichinopoly on the 25th, at Kanpur on the 26th, and at Madurai and several places in Assam on the 26th. The agitations, mass strikes, demonstrations and consequently support for the mutineers, therefore continued several days even after the mutiny had been called off. Along with this,

the assessment may be made that it described in crystal clear terms to the government that the British Indian Armed forces could no longer be universally relied upon for support in crisis, and even more it was more likely itself to be the source of the sparks that would ignite trouble in a country fast slipping out of the scenario of political settlement. It is therefore arguable that the mutiny, had it continued and confronted the threat of the RIN commander Admiral Godfrey to destroy the fleet, would have put the British Raj on the path of a maelstrom of popular movement which would have seen British exit from south-east Asia under very different circumstances than eventually happened. Certainly, the forces at Godfrey's disposal was sufficient for him to carry out his threat of destroying the RIN. However, to control the result of those actions, compounded by the outpourings of the INA trials was beyond the capabilities of the British Indian forces on whom any British General or politician (including Indian leaders) could reliably trust. The navy itself was marginal in terms of state power; Indian service personnel were at this time being swept by a wave of nationalist sentiments, as would be proved by the mutinies that occurred in the Royal Indian Air Force. In the after-effect of the mutiny, a Weekly intelligence summary issued on 25 March 1946 admitted that the Indian army, navy and air force units were no longer trust worthy, and, for the army, "only day to day estimates of steadiness could be made". It came to the situation where, if wide-scale public unrest took shape, the armed forces could not be relied upon to support counter-insurgency operations as they had been during the "Quit India" movement of 1942. The mutiny has been thus been deemed "Point of No Return"

Also, the USA's historic hostility towards Imperialism certainly made it unlikely that Atlee's government would have sought solution by force. The involvement of the Communist Party also cast a very red tinge to this ultimately mass movement that, if confronted, had the potential to have been the flashpoint for the post-war powers, as was seen in Vietnam.

However, probably just as important remains the question as to what the implications would have been for India's internal politics had the mutiny continued. This had become a movement characterised by a significant amount of inter-communal co-operation. The Indian nationalist leaders, most notably Gandhi and the Congress leadership apparently had been concerned that the mutiny would compromise the strategy of a negotiated and constitutional settlement, but they sought to negotiate with the British and not within the two prominent symbols of respective nationalism—-the Congress and the Muslim League.. By March 1947, the Congress had limited partition to only Punjab and Bengal (thus Jinnah’s famous moth-eaten Pakistan remark).

In the after-effect of the mutiny, Weekly intelligence summary issued on the 25th of March, 1946 admitted that the Indian army, navy and air force units were no longer trust worthy, and, for the army, "only day to day estimates of steadiness could be made". . It was decided that; if wide-scale public unrest took shape, the armed forces (including the airforce- for Quit India had shown how it could turn violent) could not be relied upon to support counter-insurgency operations as they had been during the Quit India movement of 1942, and drawing from experiences of the Tiger Legion and the INA, their actions could not be predicted from their oath to the King emperor .