Lesser-known engineers, contractors who sculpted Bombay in colonial era

13 June,2021 08:17 AM IST | Mumbai

Jane Borges | jane.borges@mid-day.com

An Instagram project by architect-urban researcher Esa Shaikh s the lesser-known Indian engineers, contractors and labourers, who sculpted the city of Bombay and its architecture

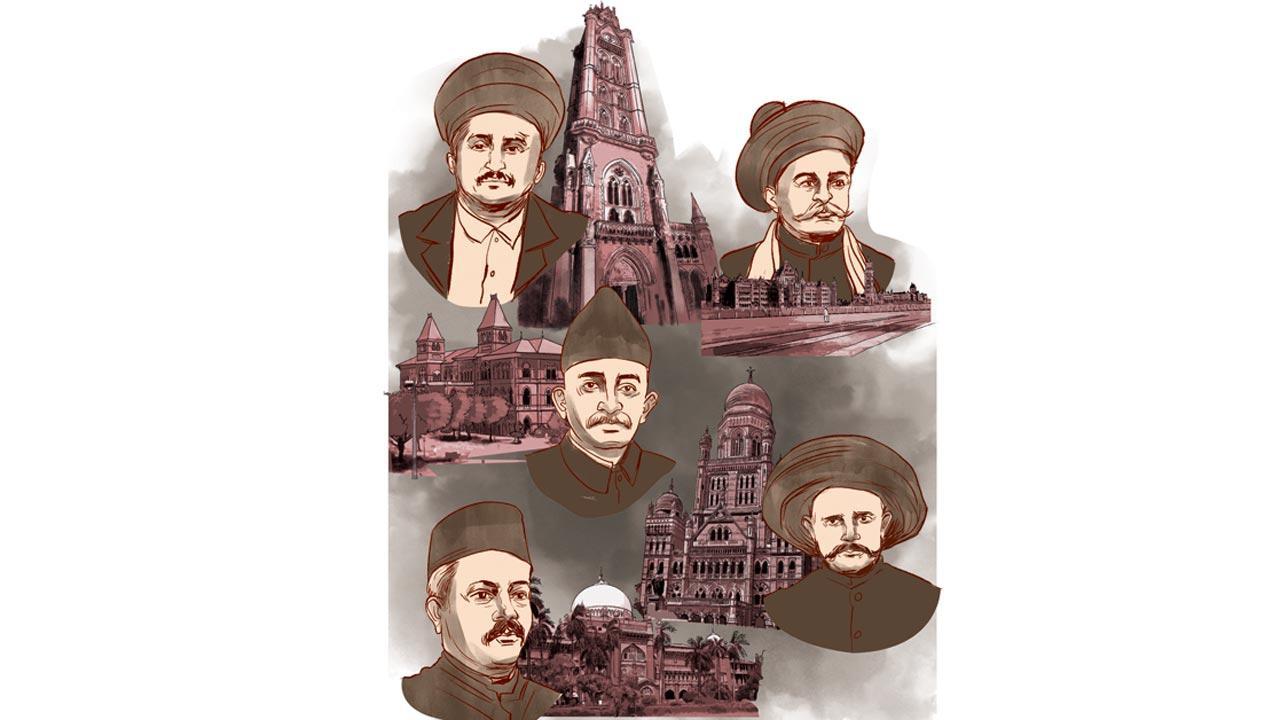

Rao Bahadur Elappa Balaram, Rao Saheb Naagu Sayaji, Rao Saheb Seth Tejoo Kaya, Vitthal Sayanna and Vyanku Baalu Kalewar

Despite growing up in Mumbai Central, architect and urban researcher Esa Shaikh rarely ever walked through the lanes of Kamathipura, a stone’s throw away from his home. Its seedy reputation preceding it, Shaikh didn’t think the neighbourhood would have anything more to offer, beyond what had already been documented in literature about the city. He admits he was wrong.

In the monsoon of 2019, while running an errand for his mum, who had

asked him to buy vegetables from a bhajiwala at the Kamathipura market,

Shaikh, 29, got caught in a downpour. Scurrying for cover, he found

himself near Shri Vitthal Rakhumai temple, in the 13th Kamathipura

Lane, which had a striking Victorian influence. “Since I am an

architect, my most natural instinct was to observe the details of the

structure. Everything from the columns and the arches were beautifully

done, and didn’t quite seem to be in sync with the other buildings in

the lane,” he recalls. Soaking wet, Shaikh was spotted by the pujari,

Mahesh Pandit, who saw him clicking pictures of the temple, and invited

him to take shelter inside. “I told him that I am Muslim and didn’t want

to upset anyone. He responded in good humour, ‘Even if aliens were to

visit my temple, I wouldn’t stop them.’” Most wall tiles were from China

and the floor was Minton. On enquiring, he learnt that the temple was

built almost 150 years ago, by one Vyanku Baalu Kalewar, whose painted

portrait hung on one of the walls inside. “Do you know he also built the

BMC headquarters?”

Pandit told him.

The columns, arches and carved interiors of Shri Vitthal Rakhumai Mandir in 13th Kamathipura Lane has Gothic influences, as it was built using some of the unused material from construction of the BMC headquarters project helmed by Vyanku Baalu Kalewar. Pics/Bipin Kokate

Shaikh, who until then, had only associated architect Frederick William Stevens with the structure, refused to believe the pujari at first. “But, then he showed me a book, where Kalewar was credited as the contractor for the building. Apparently, he also returned the Rs 68,000 that he had saved, as his construction cost was far lesser than what he had quoted [Rs 11,88,000]. Impressed by his honesty, the British government allowed him to keep the money, and also gave him all the excess material from the construction site. It’s with this material and funds that he built the temple.” This also explains the Gothic design of the temple.

Also Read: Mumbai woman steps up to donate breast milk and nurse Covid-19 orphans

More research on Kalewar led Shaikh to other contractors of 19th and 20th century Bombay, which has now inspired a new Instagram page, @contractors_of_bombay, where he documents the lesser-known Indian engineers, contractors and labourers, who sculpted the city of Bombay and its architecture in the colonial era. Assisting him on the project are Divya Bhambhra, a final year architecture student at Mumbai University, and Diya Mary Joseph, a fourth year student of Rizvi College of Architecture.

The

S Bridge in Byculla was completed by Tejoo Kaya in 1913. Kaya proposed a

design of the bridge with matchsticks, such that bullock carts could be

easily maneouvered across and trains could run beneath the bridge. It

was later approved by an engineering team. Pic/Ashish Raje

Shaikh, who studied architecture and urban design from the Mumbai University, became invested in the city’s built heritage, while working with Rahul Mehrotra of RMA Architects on Extreme Urbanism IV, which looked at affordable housing in Dongri, for Havard Graduate School of Design. A former research associate for the Urban Design Research Institute (UDRI), as part of Harvard University’s Urban Mellon Project, Shaikh also had stints with architects Bimal Patel (Ahmedabad), currently helming the Rs 20,000-crore Central Vista Redevelopment Project, and Hafeez Contractor, before he decided to “ditch the office culture to learn outside the walls of an institution”.

His new research, Contractors of Bombay, has been over two years in the making. It wasn’t easy to crack, admits Shaikh. “There was little or no research material available on the contractors.” This, he attributes, to the inherent class and caste divide in colonial Bombay.

Esa Shaikh. Pic/Anurag Ahire; Divya Bhambhra and Diya Mary Joseph

Following conversations with the pujari, he learnt about other temples in Kamathipura, many of which were heritage gems, built by other contractors. “A majority of them, including Kalewar, belonged to the Telugu Samaj. They came to Mumbai from the Nizam-ruled Hyderabad to make a living as labourers andcontractors, settling in pockets like Kamathipura, which not known to many, was one of the earliest planned neighbourhoods in the city,” says Shaikh, who currently teaches at Thakur School Of Architecture and Planning (TSAP). Even today, some of the temples in Kamathipura feed meals to people in the afternoon. It’s a tradition that goes back nearly a century, when temples looked after the children of these labourers, whose wives too, worked as bidi makers, ensuring they were well fed while their parents were away, says Shaikh.

Searching for leads, he came across a library inside one of the temples, where he learnt about the existence of a Marathi book titled, Telugu Samajcha Yogdan by late author Manohar Kadam. While the temple didn’t have a copy, he was able to source one, with the help of a friend, from the library at the Tata Institute of Social Sciences. “While discussing the contributions of the community, the author also listed the names of different contractors, and the buildings they had constructed. Many of them like Kalewar, had started out as labourers, but were later elevated, often because they understood English, making it easier to communicate with the British, or acquired enough wealth over a period of time,” says Shaikh, who has also pored over old books from Asiatic Library for his research.

Kalewar is also credited with constructing the iconic Army and Navy Building at Kala Ghoda, and several mills, including Empress and James Greaves. A friend of social activist Mahatma Jyotirao Phule, he worked to uplift members of his community.

The role of the contractor was of utmost importance in the colonial era, says Shaikh. Most of the British architects worked out of Britain. The engineers and contractors were responsible for translating their vision on paper. “And that wasn’t an easy job, considering that they also had to ensure the safety of their labourers.” He says that bamboo scaffolding wasn’t still commonly used at construction sites, and many were still reliant on ropes, among other gear.

It’s here that the work of Raosaheb Naagu Sayaji stood out. He took on the contracts of landmarks such as the Secretariat building and Bombay High Court. “It was a difficult task to build the high roof of Bombay High Court building. It took eight years for him to complete the construction,” says Shaikh, and with zero casualties and accidents. His work caught the attention of Rao Bahadur Mukund Ramchandra, the assistant engineer on site. Shaikh shares an amusing legend relayed to him by his former boss Mehrotra about Sayaji. The contractor had knocked the doors of the court, over the issue of payments. “His case was dismissed, and he was ordered to complete the construction, irrespective. A disgruntled Sayaji agreed, but not before demanding zero interference in his work.” Sculpted into the designs of the columns on the first and second floor of the court today, is a monkey-judge with one eye bandaged and holding unevenly the scales of justice. This, says Shaikh, was the work of Sayaji, cocking a snook at the system, which had left him disappointed.

Another contractor whose genius is worth noting was Rao Saheb Tejoo Kaya. Born in Kutch, Gujarat, Kaya was literate, but did not have any formal education in engineering.

A significant project that came to him was that of constructing the S bridge in Byculla. “He observed the spot for a day and then proposed a design of the bridge with matchsticks, such that bullock carts could be easily maneouvered across and trains could run beneath the bridge. He later got it checked by his engineering team, who cleared the design,” writes Shaikh in one of his posts on Instagram. The project was completed in 1913.

His other works include Currey Road Bridge (1915), Mahalaxmi Bridge, Kasturba Hospital, and the retaining wall built along the coastline, from the Radio Club to Sewri. In 1914, he was honoured with the titles, ‘Rao Sahib’ and ‘Justice of Peace’ by the British Government for his contribution to the city’s architecture.

Shaikh’s research is still a work in progress, and he hopes that this

humble attempt will help put a face to all the invisible faces that

played an important role in the city’s built history. It’s time, he

says, that the likes of Kalewar are remembered in the same vein as

Stevens.