Plague and Prejudice

Epidemics spread mistrust, as communities seek to blame their plight on outsiders or those at the margins of society. Yet the historical record reveals that outbreaks are more likely to bring people together than force them apart.

After more than half a century without a major epidemic in the West, the shock of the HIV/AIDS pandemic of the early 1980s triggered sudden interest in the socio-psychological reactions to disease. A wide range of commentators across scholarly disciplines and the popular press searched for historical parallels to AIDS and readily found them. Their message tended towards the simplistic, the anachronistic and the one-dimensional, resisting almost any attempt to detect change over time or find significant differences between epidemic diseases. In his study Ecstasies: Deciphering the Witches Sabbath (1989), the prominent Italian historian of early modern Europe, Carlo Ginzburg, concluded that: ‘The prodigious trauma of great pestilences intensified the search for a scapegoat on which fears, hatreds and tension of all kind could be discharged.’ Cultural historians Dorothy Nelkin and Sander Gilman claim that ‘blaming has always been a means to make mysterious and devastating diseases comprehensible and therefore possibly controllable’. The historian of medicine Roy Porter agreed with Susan Sontag that when ‘there is no cure to hand’ and the ‘aetiology ... is obscure ... deadly diseases spawn sinister connotations’. More recently, from Haiti, which endured a devastating earthquake followed by an outbreak of cholera in 2010, Paul Farmer in Haiti After the Earthquake (2011) proclaimed: ‘Blame was, after all, a calling card of all transnational epidemics.’

Across time, space and disease, epidemics, particularly those deemed new, lacking tested cures or effective prevention, ‘became fodder’ for all ‘sorts of irrational hatreds and prejudice’. This irrationality was supposedly directed towards the victims of epidemics or ‘others’: the poor, the outcast, the Jew, the foreigner. Assertions that epidemics’ social toxins – their negative effect on social relations – were more explosive when diseases were mysterious meant that diseases before the laboratory revolution of the 1870s, before the Scientific Revolution and certainly before Fracastoro’s mid 16th-century notion of germs should have been the most violent, with the greatest blame heaped on the victims of disease or minorities. Yet an examination of the historical record of epidemics fails to support these assertions. The most frequently cited example from antiquity of a mysterious disease sparking blame and violence is the fifth-century BC Plague of Athens. Yet any notion of such violence derives from just one tentative line in Thucydides, when inhabitants of Piraeus ‘even said that the Peloponnesians had put poison in their cisterns’. No more is heard of it when the plague reached the densely populated upper city of Athens, levelling the population by a third, where Thucydides begins his description of the plague’s socio-psychological effects. Blame does not, however, disappear entirely from Thucydides’ account. When the epidemic flared again a year later in 430, the Athenians did not blame outsiders or victims but their own leader Pericles and his stubborn continuance of the devastating war with the Spartans.

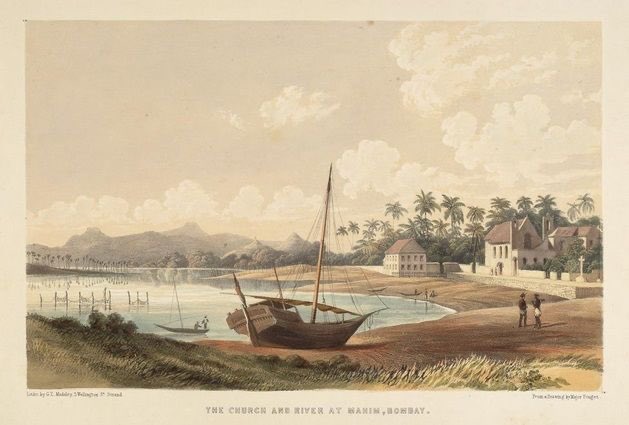

Plague in an Ancient City, by Michael Sweerts, c.1652

Plague in an Ancient City, by Michael Sweerts, c.1652

Those searching for blame and violence connected to epidemics spend little time on antiquity, leaving the impression that outbreaks were then rare. Yet, despite the survival of less than a quarter of Livy’s History of Rome (35 of 142 books), the author mentions 57 epidemics, of which modern historians have recalled only two or three. In recounting these, Livy portrays another side to the social and psychological consequences of epidemics that do not sit well with the current post-AIDS view. Instead of dividing societies, with one class or group blaming another, these epidemics often ended bitter rivalries between warring neighbours or between the plebs and senatorial classes and brought societies together, at least temporarily. Compassion, not hate, was a side effect of epidemics. In 399 BC, for example, a bitter winter followed by a summer heatwave produced a severe epidemic in Rome, fatal to humans and beasts alike and for which no cures could be found. The senate voted to consult the Sibylline Books, as was usual in times of crisis, and this led to the creation of a new sort of banquet, the lectisternium, which was open to the masses:

Throughout the City the front gates of the houses were thrown open and all sorts of things [were] placed for general use in the open courts; all comers, whether acquaintances or strangers, were invited to share the hospitality. Men who had been enemies held friendly and sociable conversations with each other and abstained from all litigation, the manacles even were removed from prisoners during this period, and afterwards it seemed an act of impiety that men to whom the gods had brought such relief should be put in chains again.

On at least three occasions the lectisternium was repeated during the fourth century BC, when particularly fatal and mysterious epidemics struck Rome. To end these scourges, the government bequeathed largesse on the population, with extended work-free holidays. Other plagues succeeded in ending class conflict between plebeians and the senatorial classes, as in 433-2 BC, when masses and elites ‘crowded before shrines, and everywhere prostrate matrons swept the floors of temples with their hair’. Fearing famine would follow pestilence, governments emptied their coffers to pay for foreign shipments of grain.

***

As with antiquity, so with the Middle Ages, a single episode, the Black Death, has fixed impressions of the social toxins aroused by a pandemic. Unlike Thucydides’ one-liner about possible biological warfare, however, accusations against Jews, beggars at Narbonne and Catalans in Sicily at the time of the Black Death fill hundreds of chronicles. Archival evidence points to over 1,000 Jewish communities annihilated between 1348 and 1350: men, women and children were burnt on islands or in synagogues, accused of poisoning wells to end Christendom. The enormity of the Black Death’s social toxins appears to be unique, not only to the Middle Ages, but to European, even world history. Yet historians have failed to mention just how short-lived these extreme reactions were. While waves of persecution against Jews continued through the late Middle Ages and early modern period, pre-modern plagues no longer triggered massacres of Jews or any other ‘others’.

Beginning around 1530, however, a second wave of plague accusations arose in Toulouse, Geneva, Lyon, Nîmes, Rouen, Paris, Turin, Milan, Palermo and smaller towns and villages. Yet the trials, tortures and executions of supposed plague-spreaders that followed cannot compare in scale, numbers, murders, or destruction with those seen during the Black Death, or with the 19th- and early 20th-century riots sparked by cholera in Europe, plague in India or smallpox in North America. Moreover, these early modern plague persecutions do not follow the reputed patterns of governments, elites or the rabble hysterically victimising suspected populations of foreigners, Jews or the poor. From the surviving trial transcripts produced at Milan in 1630 and immortalised in Manzoni’s novel I promessi sposi, those initiating the charges were poor women and the accused were insiders rather than outsiders: usually native Milanese men, including property-owning artisans, wealthy bankers and aristocrats.

Some historians have seen syphilis rather than plague as early modern Europe’s great disease of phobia and blame. Not only was it new to Europe, it was sexually transmitted, making it the perfect antecedent of AIDS. But where is the evidence that it encouraged blame or social violence? For the most part, scholars can point only to the names used to label the disease: Neapolitans called it malfrancese, the French, the mal de Naples and so on. Despite such names, no one has found a single source describing an early modern syphilis riot or a mass attack on those known, or supposed, to have spread the disease: mainly, foreign armies and prostitutes. Instead, texts such as De morbo gallico by Gabriel Falloppio, chair of medicine at Padua, expressed sympathy for Naples’ ‘most beautiful girls’, ‘propelled’ by poverty into ‘secret prostitution’. Nor did Falloppio or other 16th-century commentators blame the French, despite the standard name – morbus Gallicus – appearing in medical texts until the 17th century. In one of the most widely circulated medical tracts of the 16th century, De guaiaici medicina et morbo gallico (1519), Ulrich von Hutten explained why he used the term and immediately apologised: I do not ‘bear any grudge against a most renowned nation which is, perhaps, the most civilised and hospitable now in existence’. Two decades later, the Florentine statesman and historian Francesco Guicciardini called the disease malfrancese, but insisted that it was necessary to ‘remove the shame of the name “franzese”’, arguing that the disease had been brought from Spain and not France to Naples. He then added that the disease was ‘not exactly of that nation’ either; instead, it came from the West Indies, but he did not blame any Indian or his Italian hero Christopher Columbus ‘for making the wonderful discovery of the New World’. The physician Falloppio went further, seeing the disease springing not entirely from outside invaders but from malpractice within: unwittingly, Neapolitan bakers were partially to blame because they contaminated their bread with gypsum, thus weakening Naples’ population and contributing to the spread of the disease. The mid-16th-century Venetian physician Bernardino Tomitano also looked inward, placing the blame for the spread of syphilis in the 1530s on his own Venetian merchants, who carried it into Eastern Europe.

***

The patterns of hatred and mythologies of blame caused by epidemics changed in the 19th century with cholera. Unlike with previous diseases, including the Black Death, the hate and violence cholera provoked spread across linguistic and political borders, touching almost every country in Europe. Across strikingly different cultures, economies and regimes, the content and character of the conspiracies, the divisions by social class and the targets of rioters’ wrath were uncannily similar. Without any obvious communication among rioters from New York City to Asiatic Russia, cholera’s conspiracies repeated stories of elites masterminding a Malthusian cull of the poor, with health boards, doctors, pharmacists, nurses and government officials as the agents. Myths of poisoned wells and other sources reach back to antiquity and can be seen during the Middle Ages and early modern period, as with the slaughter of Jews and lepers in 1319-21. But unlike these massacres, 19th- and 20th-century cholera riots rarely targeted Jews or other marginal groups (and never lepers). Popular rage turned not towards the ‘other’, but against the dominant classes, especially medical professionals, local policemen and governors.

When cholera spread beyond the Ganges in 1817 into the Near East and up the Volga to reach Astrakhan in 1823, it was a new disease. Yet no reports of conspiracies or riots have yet to surface from this period. Rather, social violence followed cholera during its second tour up the Volga, when disease and hate spread in tandem throughout Europe. During cholera’s next five waves, from 1830 into the 20th century, the same myths of health workers and the state inventing the disease to kill off the poor recurred in parts of Russia and Italy long after the disease’s means of transmission were known and understood. During the 1890s, cholera riots appear to have spread more widely than ever before in Eastern Europe and Russia – into Persia, Syria and Egypt – with the estimated numbers of rioters reaching new peaks. At Astrakhan in 1892, rumours spread that the sick were being carted to hospitals to be buried alive, igniting a crowd of 10,000 to besiege the cholera hospital. Instead of attacking the disease’s victims, the protesters saw themselves as ‘liberators’, freeing the afflicted from the clutches of supposed hospital death camps. The crowd next marched to the governor’s house and burnt it to the ground. A month later, Asiatic Sarts living in and around Tashkent claimed that cholera was the work of Russian doctors poisoning them. Five thousand, ‘driven to madness over the reported cruelties to cholera patients’, invaded the Russian quarter of the city. Armed with revolvers and daggers, they plundered shops and stoned ‘all citizens in their way’. They destroyed the residence of the deputy governor and chased him through the streets, trampling, stoning, beating him to death, ‘mutilating his features beyond recognition’. Eventually, Cossacks quelled the revolt after killing 70 and wounding hundreds. Between these two events numerous smaller but deadly cholera riots swept down the Volga.

Cholera riots became especially widespread in Italy. In the first and most studied wave in 1835-6, social violence was confined almost entirely to Sicily. That was far from the case during Italy’s last major cholera epidemic, of 1910-11, even though mortality rates were a fraction of previous outbreaks and despite the fact that the disease’s water-bound transmission had been known for half a century. At Massafra in Puglia, for instance, the old cholera myths of hospitals as death chambers for the poor persisted. Crowds of around 3,000 stormed the cholera hospital and ‘liberated’ the patients, whom they paraded triumphantly through the streets. Prominent government officials and doctors were killed, nurses were thrown out of windows, equipment was smashed and the hospital set ablaze.

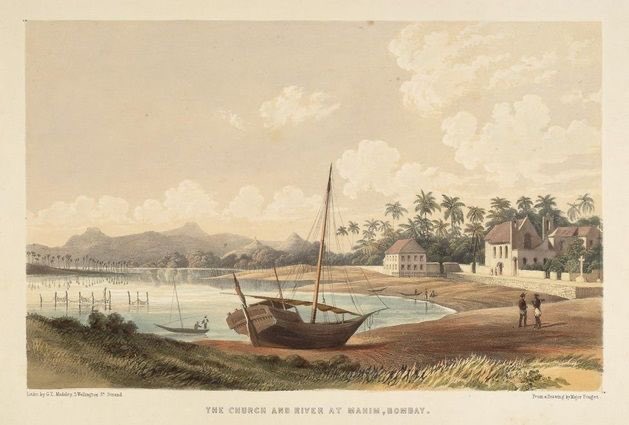

A costume designed to protect doctors from plague, French, 1720

A costume designed to protect doctors from plague, French, 1720

The incident that gained most publicity occurred at Verbicaro, a town of 6,000 north of Cosenza in Calabria. At the end of August 1911, 1,200 ‘rebels’ attacked the town hall while the mayor was convening a meeting. The first to be seized was a clerk, who several months earlier had been involved in drafting the town’s census. A woman struck his head with a stick, another shot him and a third hacked his head off with a pruning knife. The attack was not random. Harking back to a basic plot of cholera conspiracies, the peasants believed the census was the town’s first step in selecting those ‘for the sacrifice’ to ease Italy’s overpopulation. Armed with spades, knives, sticks and agricultural implements, women, boys and men knocked down telegraph poles, cut the wires, wrecked the town hall, burnt its archives, the court house, the telegraph office and the mayor’s house and released prisoners from gaol. The mayor, a town clerk and a judge fled. A group of 11, including three women, caught the clerk and ‘hacked him to pieces’. On reaching the train station, the judge ‘died of fright’. Fearing reprisals, half of Verbicaro’s population fled to the mountains, leaving cholera corpses strewn through streets. The mayor escaped, but two days later was ordered to return and was immediately murdered, repeating the fate of his grandfather, mayor of Verbicaro in 1857, when a previous cholera uprising swept through town.

***

Southern Italian towns were not the only ones to have been afflicted by cholera’s social toxins. Large-scale cholera riots, for instance, had erupted in Tuscany’s industrial port of Livorno in 1857 and 1893. In 1911, similar riots spread through seaside resorts outside Rome at Ansio, Nettuno and Terracina. The authorities in Segni, southwest of Rome, which experienced just five cholera cases, requisitioned a hospital and lazzaretto to quarantine suspected cases. Immediately ‘the idea spread among ignorant people’ that the authorities, municipal and national, had planned a ‘massacre of the innocents’ to poison the town. ‘A mob’ of 3,000 marched on the town hall demanding the release of cholera patients, stoned carabinieri and battered down the town hall’s door, ‘intending to sack and destroy the place, and murder the mayor and health workers’, who they accused of inventing the disease. The papers reported women as being ‘particularly ferocious’. One seized a carabiniere, threw him to the ground and stomped on him. Another grabbed the municipal flag and shouted: ‘To the hospital.’ The ‘mob’, heeding her command, surged through town, crying ‘Death to the doctors and nurses’. They succeeded in removing the cholera patients from the hospital, carrying them ‘in a procession to their homes’.

We can reach some conclusion from these examples. First, even though a nexus of hate driven by epidemics may have been on the rise in the 16th and early 17th centuries, with the trials of supposed plague spreaders, they were short-lived and mild in comparison to what followed with the much more widespread social unrest from cholera in 19th- and early-20th-century Europe. Second, with cholera the unrest was more than principally an urban phenomenon confined to ten or so cities. In the British Isles for the 13-month period, December 1831 to January 1833, for instance, I have found 72 cholera riots, many with crowds in the thousands, that attacked physicians and destroyed cholera hospitals. In Ireland and Scotland in particular, these occurred not only in the principal cities but in small towns and villages such as Ardee, Kilkenny, Killineer, Ballina in Ireland and Paisley, Wick, Pathhead (Kirkcaldy), Leith and Ivergordon in Scotland. Third, scientific discoveries of cholera’s bacterial agent and mechanisms of transmission did not end or even dampen cholera’s social violence or the mythologies that fuelled it in and around the large and sophisticated cities of western Europe. In Russia and Italy these riots continued into the 20th century, becoming as widespread and frequent as they had been in the 1830s. Finally, comparison of epidemics shows that the social configurations of hate were not one-dimensional or static across time and place as the recent literature inspired by the AIDS experience would have us believe. Responses to cholera differed markedly from the slaughter of Jews during the Black Death or the 16th- and 17th-century plague trials, which reveal a wide variety of perpetrators and victims. Instead of blaming and scapegoating the poor, Jews, foreigners and other marginal populations, cholera’s mythologies of hate funnelled blame and violence in the opposite direction: marginal groups such as Asiatic Sarts in Russian cities, impoverished Irish women and boys in New York, Liverpool and Glasgow, peasants, fig-growers and unemployed fishermen in Puglia and women and children in other Italian towns targeted physicians, pharmacists, nurses, mayors and other government officials as the ones purposely spreading the disease. Nor have such conspiracy theories connected with epidemics disappeared, as attested by attacks in 2014 on the Red Cross in West Africa, accused of inventing the Ebola virus, or more recently with charges that a biotech company had purposely released the superbugs causing the Zika virus in Brazil to reduce global population.

***

Curiously, the one disease of the late 19th- and early 20th-century to correspond most closely with the current view of big epidemics triggering blame against ‘the other’ did produce the most widespread and frequent social violence in US history: smallpox. Yet historians have hardly recognised its social toxins, especially after the few anti-inoculation riots of the colonial period. As with cholera, smallpox produced mass revolts in which the poor and immigrants railed against health boards and municipal governments, as seen in three large riots and a series of smaller ones in Milwaukee from September 28th to December 31st, 1894, or one comprised of Mexican immigrants at Laredo, Texas in March 1899. But from the epidemic of 1881 to the second decade of the 20th century, smallpox sparked numerous grizzly acts of inhumanity against the victims of this disease. Those perpetrating the violence were white, propertied farmers and business men – ‘the better sort of citizens’ – and their targets were Amerindians and recent immigrants – Chinese, Bohemians, ‘tramps’ – but, above all, blacks. Time allows only two interconnected examples. There are many more:

April 3 [1896]. William Haley, colored, is in the Memphis hospital … He was badly beaten about the head and arms and wounded with bullets in three places. Smallpox originated in Haley’s house several months ago and for this he was whitecapped by a mob of twenty persons, clubbed with guns and shot, before the eyes of his wife and children.

The epidemic spread from Memphis to Bessemer, Alabama. A pesthouse was erected for the patients, nine tenths of whom were ‘negroes’. A mob, ‘composed of white farmers living in the neighborhood’ came at night ‘and riddled [the patients] with bullets’. Asked to justify their crime, they replied that ‘this is the best and quickest means of ridding the town of smallpox’.

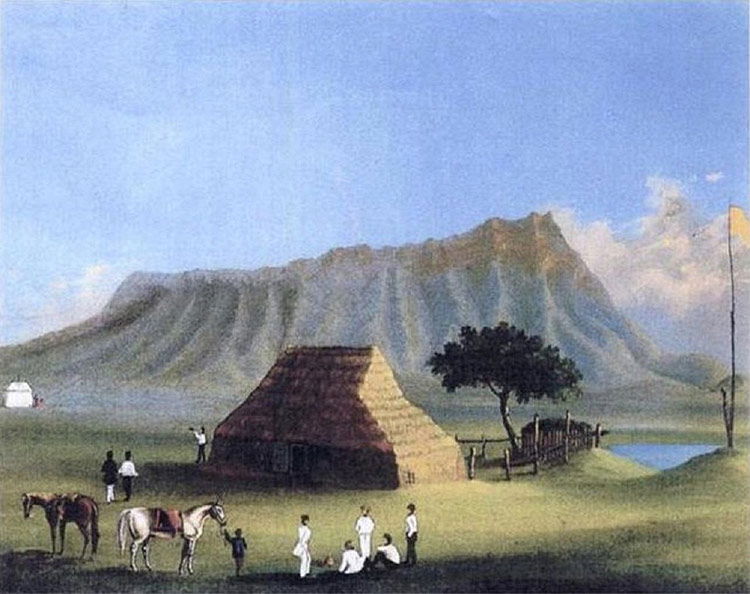

Smallpox quarantine station in Hawaii, by Paul Emmert, 1853

Smallpox quarantine station in Hawaii, by Paul Emmert, 1853

Other epidemics of the late 19th and early 20th century had more complex alignments between perpetrators and their targets, such as the plague riots in India, which produced general strikes and crowds even larger than those of cholera riots in Russia. Indian protests, however, often had a clear political agenda. British doctors and soldiers strip-searching young Indian girls for signs of plague sparked the Bombay riot of the Julai weavers in March 1898. Soon after, 15,000 dockers, labourers and cartmen supported the protest with a general strike. Journalists and intellectuals joined in, decrying the government’s needless and abusive quarantines, body searches and destruction of homes and religious shrines. Rather than tearing Indian societies apart, the plague united groups across class and castes and Hindus with Muslims against the backward and oppressive health measures of the British.

***

Not all epidemics of the modern period produced blame, hate or collective violence. Yellow Fever in the United States and the Great Influenza of 1918-20 throughout the world remained mysterious in their modes of transmission and their causal agents far longer than cholera, killed millions more and could possess frightening, disgusting signs and symptoms. Yet neither sparked large-scale collective violence or widespread blame of others, whether the impoverished or the elites. Instead, as with epidemics in antiquity, they brought societies together across race, ethnicity and class, even within contexts of rising social, political and racial tensions, as with the Yellow Fever outbreak in New Orleans in 1853, which arose on the eve of the Civil War, when regional and racial antagonisms were sharpening. The city’s blacks, believed to have had greater immunity to the disease, crossed class and racial lines to nurse stricken whites and, in turn, the white middle classes praised them for their bravery. In El Paso, Texas in October 1918, at the height of the Great Influenza, anti-Mexican sentiment had been brewing thanks to Zapata’s incursions on US soil and the rise of the Ku Klux Klan. Yet debutante ladies, for the first time in their lives, crossed into the city’s poorest Mexican neighbourhoods where influenza cases were at their highest and risked their lives, sweeping floors, setting up soup kitchens and treating the dangerously ill.

The extraordinary variety of reactions to the hazards and shocks of epidemic disease defy the widespread, one-dimensional views that have become dominant since the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Curiously, activists’ and scholars’ understanding of the psychological, social and political effects of HIV/AIDS itself began to shift in the 1990s from one that stressed hate, violence and blame to one in praise of the way in which the disease inspired volunteerism, community organisation, self-sacrifice and compassion. Instead of retelling stories of discrimination in jobs, education and housing or the homophobic pronouncements of right-wing politicians and television evangelists, the literature began to emphasise the political gains won by lesbians and gays, sex workers and, in Africa, women, and how AIDS reshaped more progressive doctor-patient relations and redefined the family. This shift, however, has yet to inspire scholars to revisit the long history of epidemics. This second, more nuanced and positive (though hardly rosy) view of AIDS forms a new template to rewind the movie reel (de rérouler à reculons), as the great French medievalist Marc Bloch once put it, for understanding the distant past from the perspective of the present.

Samuel Cohn is Professor of Medieval History at the University of Glasgow