[Victorian Web Home —> Political History —> Victoria and Victorianism —> The Empire —> British India —> Next]

Image scans and photographs by the author. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL or credit the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images to enlarge them.]

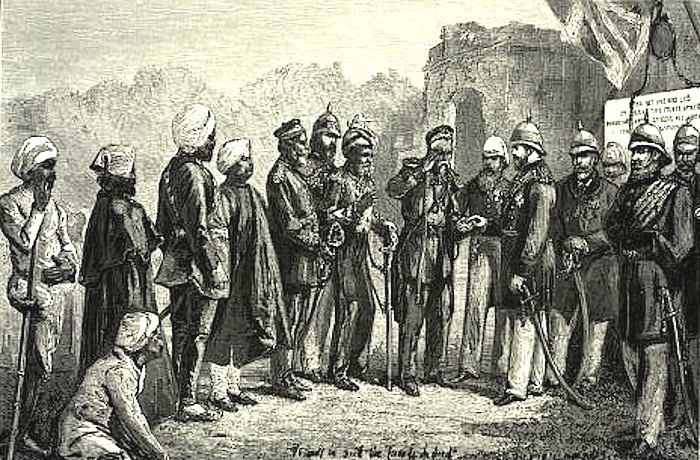

Grand Chapter of the Star of India at Calcutta, 1 January 1876. The Prince of Wales investing the Maharajah of Joodphore [Jodhpur] with the Order. Source: Tinted engraving from the collection of the Imperial Hotel, Janpath, New Delhi, reproduced by kind permission of the hotel. This was one of the many highlights of the trip, and perhaps the picture that has been reproduced most often.

Bombay and Environs

Prince Albert Edward (Bertie), Queen Victoria's eldest son, set sail from London on 11 October 1875 on the royal ship HMS Serapis, and arrived at Bombay in India just under a month later, on 8 November. There were altogether fifty men in the party, the next highest ranking to the Prince being the Duke of Sutherland, followed by Sir Bartle Frere. Chosen to record the visit were the Prince's Honorary Private Secretary, William Howard Russell (1820-1907), who reported on it for the Times, and the artist Sydney P. Hall (1842-1922), who was responsible for the illustrations in Russell's subsequent book about it. During the next seventeen weeks the Prince made an extensive tour of the country, meeting the colonial elite, being entertained in style by the native princes, bestowing honours, attending functions of all kinds, receiving costly gifts, participating in animal shoots and sporting events, dallying with one or two English belles, and so on. As Russell would note later, by the time he left, the Prince knew "more Chiefs than all the Viceroys and Governors together and [had] seen more of the country ... than any living man" (521). The tour was as extensively covered at home as it was extensive, but it is not much discussed now. Yet it demonstrated the surprising strengths of the future Edward VII, and had very significant repercussions for the Raj.

Left to right: (a) Sketch Map to Illustrate the Tour of HRH The Prince of Wales. Source: Russell, facing p. 1. (b) The First Step on Indian Soil: Landing at Bombay. Source: Russell, facing p. 115. (c) Shamzadan [Crown Prince] Passes! Native Band at Poonah. Source: Russell, facing p. 180.

Having acquitted himself well at his first royal audience in Bombay, the Prince then made it his base for some side trips into the neighbouring areas. First, he went eastwards by train for Poona, almost 120 miles away, making the scenic ascent of the Bhore Ghat, that had been such a massive feat of railway engineering, on the way. Poona (present-day Pune) was a cantonment area and the summer residency of the Governor of Bombay. Then, having been very handsomely received, presented with many gifts from rajahs and heads of state, and taken his first elephant ride, the prince returned to Bombay briefly before setting again on another scenic train trip, several times further and towards the north this time, across various bridges over rivers and estuaries, to the princely state of Baroda. On 18 November the special train was met at Baroda station by the thirteen-year-old Gaekwor of Baroda, who had already gone to greet the Prince in Bombay. Two days later, the Prince was off for his first shooting event or shikar. It was the beginning of a veritable orgy of such big-game hunting expeditions. This particular visit included a form of entertainment that the young Gaekwor particularly enjoyed: animal fights, between elephants, rhinos, and rams, and this caused some comment at home. The Aberdeen Journal perhaps struck the right note, acknowledging their brutality, but pointing out that the Prince was "not there to run amuck at anything that offends his more humane sensibilities," adding (surely correctly) that his hosts "were doing their best, from the highest to the lowest, to welcome him after their fashion." There is no hint, however, that the Prince's sensibilities were affected!

South to Ceylon, and up to Madras

Ceylon — The Dead Elephant. Source: Russell, facing p. 283.

On his return to Bombay, the Prince set off by the royal ship Serapis again, on a voyage to South India, first along the western coast, stopping on the way at Goa and the historic port of Beypore in Kerala. From there the Serapis sailed to Ceylon (present-day Sri Lanka), where the Duke of Sutherland surprised their hosts with his engineering skills, driving the royal train "round that dizzy promontory the 'Sensation Rock.'" At some point he also tightened up a coupling "with all the skill and proper application of strength" (Wheeler 12). The Prince proved himself in a more predictable and indeed expected way, by performing well in a particularly bloody and triumphalist elephant shoot. This again provoked controversy in the British press, understandably so, because elephant-hunting had only recently been banned by the colonial government (see "Elephants in Ceylon"). But it served to confirm his princely status: "Shooting an elephant was a public act, a performance where the prince was a principal actor: he must be seen to kill the great beast" (Ridley 177-78).

This great loop of the subcontinent was less than halfway through. Returning to India, the Prince and his party set off again by train to Madurai in Tamil Nadu, at the start of a rail journey that took them up 82 miles up the eastern coast to Trichinoploy (Tiruchchirapalli), and a further 198 miles to Madras, their main stop on the way to the seat of the Raj, at Calcutta. Their reception at Madras was again phenomenal:

As they packed themselves together to await the coming of the Prince, the women grouped by hundreds, the men in similar numbers, the front rank seated on the ground, those behind kneeling, while the rearmost of all stood up and peered over the heads of the others, they formed a vast and far-extending mass, to see which a journey of even eleven thousand miles was not too much. Every now and then carriages containing Bajahs and Maharajahs is picturesque costumes, escorted by the Governor's bodyguard in bright scarlet and gold uniforms, and followed by parties of their own wild-looking horsemen, drove past; and at last the Prince himself came, cheered vociferously by the crowd. [Gay 162]

The days in Madras were crammed with sight-seeing, and included a spectacular late night entertainment — one so late, in fact, the the prince himself only arrived at midnight.

Calcutta to Benares, via Bankipur

Left: Prinsep Ghat. Designed by W. Fitzgerald, this striking ionic landing stage on the Hooghly River at Calcutta was built in memory of James Prinsep (1799-1840), the eminent Oriental scholar, in 1843. It has recently been restored. Right: Benares. Illustration by Mortimer Menpes. Source: Finnemore, facing p.48.

The Prince of Wales finally arrived in Calcutta, the seat of the Raj, on 23 December. Here he stayed at the Raj Bhavan, and was able to attend the Christmas Day service at St Paul's Cathedral, before being conveyed to Prinsep Ghat, where huge crowds had gathered to see the flag-bedecked Serapis and catch a glimpse of the Prince himself. Thence the royal party went by river on the short trip to the French settlement of Chandernagore (present-day Chanannagar, just north of Kolkata) before the Serapis docked at Prinsep Ghat again. After the next few busy days in Calcutta, the Chapter of the Order of the Star of India was held on New Year's Day, with the prince dispensing honours, including knighthoods, to various Maharajas and high ranking officials. On 3 January, the prince received an honour himself: he was made honorary Doctor of Laws at Calcutta University (Wheeler 218).

Then he was off again, on the next leg of a tour which took him by train and boat along the Ganges. At the next stop, Bankipoor (now Bankipur) in Patna, Bihar, on the southern bank of the Ganges, he was met by Sir Richard Temple, and all the officials of the district, along with troops, police and crowds of onlookers. Although this was no princely state, again, the reception was extravagant:

Sir Richard Temple had made preparations to show what a Lieutenant-Governor of Bengal could do. His Court, if not equal in splendour to that of the Viceroy, satisfied the spectator that he was a satrap [ruler] of no ordinary magnitude and magnificence.... Considering that there are, it is said, less than 100,000 Europeans in India, it was surprising to see what an assembly of ladies, in the most charming bonnets and most correct costumes, were waiting to welcome him. The avenue to the Durbar tent was lined by nearly four hundred elephants, caparisoned with great richness, the howdahs filled with people in gala dresses. The great multitude Europeans on one side of the way and natives on the other was loyal and picturesque; the loyalty of the Europeans expressed by cheers, waving of handkerchiefs, playing of bands, and discharges of cannon; the picturesqueness afforded by Rajas, Nawabs, and natives of inferior dignity. [Russell 382]

All this, however, just for a three-hour break, after which the Prince returned to the railway station, and then travelled on to the holy city of Benares, with its spectacular ghat and its unforgettably palatial background. Another lavish reception awaited him from the Maharajah there. The Daily Telegraph correspondent realised how much this place would mean to "a believer in Shiva, a red-turbaned, shuffling, white-petticoated, olive-coloured native of Hindostan, with his heart set upon visiting the sacred city of India," and knew that such a one "would leap for joy; would forget the mist and the dimness, the chilly wind and clammy air, the chance of having no bed, and possibly no board either, and rejoice with exceeding joy at the prospect of plunging in the Ganges next morning, and washing away what peccadilloes and worse might cling to his soul" (Gay 218). But from his own description, it is clear that this observer did not quite share the enthusiasm, and had no intention whatsoever of dipping into a river which "might, were it not so sacred, be called very dirty" (220). It is remarkable that the Prince and his party not only kept up the pace set for them by the India Office at home, but also managed (apart from some knocks in a pig-sticking event and the Prince's catching a cold in Calcutta) to avoid its health hazards.

Lucknow and Kanpur

Left to right: (a) Veterans at Lucknow. Source: Russell, facing p. 393. (b) Visit to the Cawnpore Memorial. Source: Russell, facing p. 401.

The stop at Lucknow was special. Here, the element of gorgeous and spectacular entertainment gave way to poignant and stirring memories of the famous siege and its relief, during the 1857 Mutiny. A Celtic cross had long since been raised in the Residency garden in memory of Sir Henry Lawrence and the European officers and men who died then; now the Prince laid the first stone of a monument outside the garden, to the Indians who also died with them. It was surely the most emotional ceremony in which the Prince took part in India. In the presence of the assembled troops, the English flag was raised outside the battle-scarred ruins of the old Residency. Trumpets sounded, salutes were made, drums rolled and cannon fired.

The salute over, the Prince desired that all the survivors of the defence might be presented to him. The picture... was touching in the extreme. Some two hundred old warriors filed past. First came the officers.... They were followed by sixteen native officers and non-commissioned officers who had taken part.... and lastly, and on which all eyes turned, was a mixed band of decrepit warriors, and young men who, as mere boys, had done their duty nobly within the walls.... In some cases their bodies were supported by friends, and their palsied arms were with difficulty made to give a last salute.... Several veterans came forward in the old stiff uniforms of the East India Company's service, and having swords covered with the rust of twenty years. During the scene, many ladies, some of whom had lost sons in the relief, were in tears. Every one was affected. [Wheeler 227-28]

The Chief Commissioner for the region of Oude (present-day Awadh) declared, in the speech that followed, that the behaviour of the sepoys at Lucknow, who voluntarily stood by the British during the siege, "was simply without a parallel in the annals of the world" (qtd. in Wheeler 228). Amongst the other sights that the Prince was shown in Lucknow was the "square grey tomb, with a shelving stone on the top" of Major Hodson, whose elaborately carved monument can be seen in Lichfield Cathedral.

The royal party then set off for Delhi, with a couple of hours' pause in the evening at Cawnpoor (now Kanpur), where the Prince paid his respects at the spot of perhaps the most notorious of the atrocities committed during 1857 on both sides, when two hundred or so British women and children were butchered and thrown into a well (for an objective assessment, see Keay 442). Here stood Baron Marochetti's The Angel of Pity memorial. Marochetti loved to design and sculpt angels, and this is one of his finest. "I cannot describe the effect of the bright moon's rays on the white marble work — or how the whole memorial stood out in its lonely grandeur on that delightful night," wrote a member of the party (Gay 237-38). The Prince also inspected the Memorial Gardens and the only recently completed church there, now called the Kanpur Memorial Church, to which the monument has since been moved.

Delhi

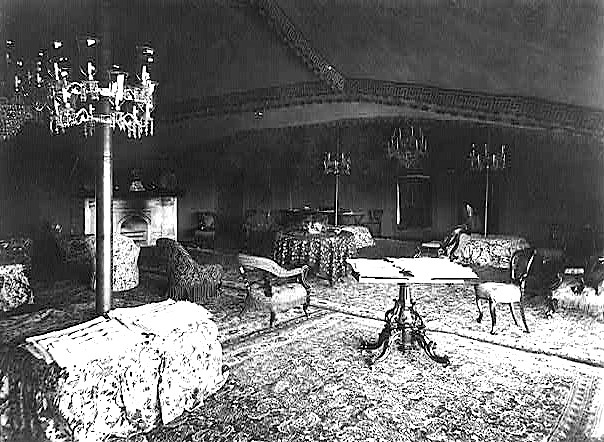

Left to Right: (a) Interior of the Royal Drawing Room Tent in Delhi. Source: black & white film copy neg. Library of Congress Digital Image, reproduction no. LC-USZ62-67684. (b) The Qtab Minar, a victory tower with twelfth-century origins, leans slightly now, and it is no longer possible to climb up it, as the Prince did. (c) Ruins of the Quwwat-ul-Islam Masjid in the complex, also of twelfth-century origin.

Travelling overnight by train, the royal party reached Delhi on 11 January, where they spent six days. There was the usual tremendous welcome, and again the visit was imbued with memories of 1857: most of the activities during the stay were of a military nature. As they had done at Benares, the guests stayed under canvas, and again in considerable luxury. The Prince's tents in particular were splendidly appointed: "The camp was a more luxurious bivouac than any monarch sleeping in the tented field has ever enjoyed" (Wheeler 235). There was a levee, followed by a glittering review of both British and Indian regiments, with the Prince sporting the uniform of a Field Marshal, and extensive military manoeuvres, with the Prince himself taking part on a charger. But amid all this there was still time for entertainment of a gentler kind, and some sightseeing:

At the Kootab there was a small camp pitched for the occasion. There was a military band, and lunch was laid in a large marquee. Many ladies were invited from Delhi. The Prince mounted to the summit of the Kootab, said to be the highest pillar in the world (it measures 238 feet in height), and viewed the wide-spread ruins of forts, tombs, mosques, and cities. [Russell 414]

It is easy to see, from the various accounts of the Prince's stay here, how Delhi, with its long and fascinating history, more recent associations for the British, and excellent railway connections, later came to be chosen as the capital of the Raj.

It is equally easy to see how the glowing reports of Bertie's triumphal progress up to this point played on the Queen's desire to be called Empress of India. As for the Prince himself, indefatigable, keen to engage in the pageantry of every occasion, appreciative of and sympathetic towards the Indian princes and colonial representatives alike, responsive to the common people as well, he was proving to be a wonderful ambassador for the British crown. The Queen's next move was not something he himself foresaw or wanted: "I could never consent to the word 'Imperial' being added to my name," he told Disraeli (qtd. in Ridley 181). Nor was he even consulted about it (see Ridley 181). But exactly a month after the royal party left Delhi on the next leg of their tour, Disraeli was putting forward to Parliament the Royal Titles Bill.

Related Material

- Part II: From Delhi to Bombay

- The Qtub Minar and the Victorians

- The 1857 Indian Mutiny (also known as the Sepoy Rebellion, the Great Mutiny, and the Revolt of 1857)

- Royal Titles Bill (Second reading)

- New Crowns for Old Ones (John Tenniel's cartoon lampooning the Royal Titles Bill)

Sources

Bisht, B. M. S., ed. "Titbits from my Archives: The Prince of Wales' Railway Journeys in India, 1875-1876" (edited and clearly dated excerpts from Russell, giving a good idea of the tour in brief). IRFCA (Indian Railways Fanclub). Web. 30 March 2014.

"Elephants in Ceylon." The Times. 25 May 1875: 11.

Finnemore, John . Peeps at Many Lands: India. Illustrated by Mortimer Menpes. London: Adam and Charles Black, 1910. Internet Archive. Web. 30 March 2014.

Gay, J. Drew. The Prince of Wales in India, or From Pall Mall to the Punjaub. New York: R. Worthington, 1877. Internet Archive. Web. 30 March 2014.

Keay, John. A History of India. Pbk ed. London: HarperCollins, 2001.

"The Prince of Wales in India." The Aberdeen Journal. 24 November 1875: 3. 19th Century British Newspapers (Gale). 30 March 2014.

KING'S 'LEVEE' =the simple act of getting up in the mornin WHICH was raised to a ceremonial custom at the court

............................................,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,

The levee (from the French word lever, meaning "getting up" or "rising")[1] was traditionally a daily moment of intimacy and accessibility to a monarch or leader, as he got up in the morning. It started out as a royal custom, but in British America it came to refer to a reception by the sovereign's representative, which continues to be a tradition in Canada with the New Year's levee; in the United States a similar gathering was held by several presidents.

History

France

In Einhard's Life of Charlemagne, the author recounts the Emperor's practice, when he was dressing and putting on his shoes, to invite his friends to come in and, in case of a dispute brought to his attention, "he would order the disputants to be brought in there and then, hear the case as if he were sitting in tribunal and pronounce a judgement."[2]

By the second half of the sixteenth century, it had become a formal event, requiring invitation.[3] In 1563 Catherine de' Medici wrote in advice to her son, the King of France, to do as his father (Henry II) had done and uphold the practice of lever. Catherine describes that Henry II allowed his subjects, from nobles to household servants, to come in while he dressed. She states this pleased his subjects and improved their opinion of him.[4]

This practice was raised to a ceremonial custom at the court of King Louis XIV.[5] In the court etiquette that Louis formalised, the set of extremely elaborate conventions was divided into the grand lever, attended by the full court in the gallery outside the king's bedchamber, and the petit lever that transpired in degrees in the king's chamber, where only a very select group might serve the king as he rose and dressed.[5] In fact, the king had often risen early and put in some hours hunting before returning to bed for the start of the lever. Louis's grandson, King Philip V of Spain, and his queen typically spent all morning in bed, as reported by Saint-Simon, to avoid the pestering by ministers and courtiers that began with the lever.

The king's retiring ceremony proceeded in reverse order and was known as the coucher.

The successors of Louis XIV were not as passionate about the monarch's daily routine and, over time, the frequency of the lever and coucher decreased, much to the dismay of their courtiers.[6]

Great Britain

When the court of Charles II of England adopted the custom, first noted as an English usage in 1672,[7] it was called a levée. In the 18th century, as the fashionable dinner hour was incrementally moved later into the afternoon,[8] the morning reception of the British monarch, attended only by gentlemen, was shifted back towards noon.

The practice of holding court levées was continued by the British monarchy until 1939. These took the form of a formal reception at St James's Palace at which officials, diplomats, and military officers of all three armed services, were presented individually to the sovereign. A form of civil uniform known as Levée dress was worn by those entitled to it, or else naval or military uniform, or court dress. Participants formed a queue in the Throne Room before stepping forward when their names and ranks were called. Each then bowed to the king who was seated on a dais with male members of his family, officials of the Royal Household and senior officers behind him.[9]

Levees in the British Empire and Commonwealth

Levée ceremonies were held by regal representatives of the British Empire, such as the Viceroy of India, the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, governors general and state/provincial governors/lieutenant governors.[10] The ceremonial event continues to be held in a number of Commonwealth countries. The New Year's levee is still held on New Year's Day in Canada, by the Governor General of Canada, the lieutenant governors, the Canadian Armed Forces, and various municipalities across the country.

United States

By the 1760s, the custom was being copied by the colonial governors in British America, but was abandoned in the United States following the American Revolutionary War. Beginning in 1789, President George Washington and First Lady Martha Washington held weekly public gatherings and receptions at the presidential mansion that were called levees. Designed to give the public access to the president and to project a dignified public image of the presidency, they were continued by John and Abigail Adams, but not by Thomas Jefferson.[11] English writer Harriet Martineau, after witnessing a White House levee during the second term of Andrew Jackson's presidency, remarked on how egalitarian the levee was in every respect but one:

I saw one ambassador after another enter with his suite; the Judges of the Supreme Court; the majority of the members of both Houses of Congress; and intermingled with these, the plainest farmers, storekeepers, and mechanics, with their primitive wives and simple daughters. Some looked merry; some looked busy; but none bashful. I believe there were three thousand persons present. There was one deficiency,—one drawback, as I felt at the time. There were no persons of colour ... Every man of colour who is a citizen of the United States has a right to as free an admission as any other man; and it would be a dignity added to the White House if such were seen there.[12]

Abraham Lincoln held a levee on New Year's Eve 1862.[13]

Louis XIV's lever

The ceremony at Versailles[14] has been described in detail by Louis de Rouvroy, duc de Saint-Simon. Louis XIV was a creature of habit and the inflexible routine that tired or irritated his heirs served him well. Wherever the king had actually slept, he was discovered sleeping in the close-curtained state bed standing in its alcove, which was separated from the rest of the chambre du roi by a gilded balustrade.[15] He was woken at eight o'clock by his head valet de chambre—Alexandre Bontemps held this post for most of the reign—who alone had slept in the bedchamber. The chief physician, the chief surgeon and Louis' childhood nurse, as long as she lived, all entered at the same time, and the nurse kissed him. The night chamberpot was removed.

Grande entrée

Then the curtains of the bed were drawn once again and, at a quarter past eight, the Grand Chamberlain was called, bringing with him the nobles who had the privilege of the grande entrée, a privilege that could be purchased, subject to the king's approval, but which was restricted in Louis' time to the nobles. The King remained in bed, in his nightshirt and a short wig. The Grand Chamberlain of France or, in his absence, the Chief Gentleman of the Bedchamber presented holy water to the king from a vase that stood at the head of the bed and the king's morning clothes were laid out. First, the Master of the Bedchamber and the First Servant, both high nobles, pulled the king's nightshirt over his head, one grasping each sleeve. The Grand Chamberlain presented the day shirt which, according to Saint-Simon, had been shaken out and sometimes changed, because the king perspired freely. This was a moment for any of those with the privilege of the grande entrée to have a swift private word with the king, which would have been carefully rehearsed beforehand to express a request as deferentially as possible while also being as brief as possible. The King was given a missal and the gentlemen retired into the adjoining chambre du conseil (the "council chamber") while there was a brief private prayer for the King.

Première entrée

When the King had them recalled, now accompanied by those who had the lesser privilege of the première entrée, his process of dressing began. Louis preferred to dress himself "for he did almost everything himself, with address and grace", Saint-Simon remarked. The King was handed a dressing-gown, and a mirror was held for him, for he had no toilet table like ordinary gentlemen. Every other day the King shaved himself. Now, other privileged courtiers were admitted, a few at a time, at each stage, so that, as the King was putting on his shoes and stockings, "everyone" — in Saint-Simon's view — was there. This was the entrée de la chambre, which included the king's readers and the director of the Menus Plaisirs, that part of the royal establishment in charge of all preparations for ceremonies, events and festivities, to the last detail of design and order. At the entrée de la chambre were admitted the Grand Aumônier and the Marshal of France and the king's ministers and secretaries. A fifth entrée now admitted ladies for the first time, and a sixth entrée admitted, from a privileged position at a cramped backdoor, the king's children, legitimate and illegitimate indiscriminately — in scandalous fashion Saint-Simon thought — and their spouses.

The crowd in the chambre du Roi can be estimated from Saint-Simon's remark of the King's devotions, which followed: the King knelt at his bedside "where all the clergy present knelt, the cardinals without cushions, all the laity remaining standing".

The King then passed into the cabinet where all those who possessed any court office attended him. He then announced what he expected to do that day and was left alone with those among his favourites of the royal children born illegitimately (whom he had publicly recognised and legitimated[16]) and a few favourites, with the valets. These were less pressing moments to discuss projects with the King, who parcelled out his attention with strict regard for the current standing of those closest to him.

Grand lever

With the entry of the King into the Grande Galerie, where the rest of the court awaited him, the petit lever was finished, and with the grand lever the day was properly begun, as the king proceeded to daily Mass, sharing brief words as he progressed and even receiving some petitions. It was of these occasions that the King habitually remarked, in refusing a favour asked for some noble, "We never see him", meaning that he did not spend enough time at Versailles, where Louis wanted to keep the nobility penned up, to prevent them interesting themselves in politics.

For the aristocracy

Among the aristocracy, the levée could also become a crowded and social occasion, especially for women, who liked to put off the donning of their uncomfortable formal clothes, and whose hair and perhaps make-up needed prolonged attention. There is a famous depiction of the levée of an 18th-century Viennese lady of the court in Richard Strauss's later opera Der Rosenkavalier, where she has her hair dressed while surrounded by a disorderly crowd of tradesmen touting for work or payment, and other petitioners, followed by a visit from a cousin. The second scene of William Hogarth's A Rake's Progress shows a male equivalent in 1730s London.

In the French engraving Le Lever after Freudenberg, of the 1780s, gentle social criticism is levelled at the lady of the court; that she slept without unlacing her stays, apparently, perhaps can be seen as artistic licence. Her maids dress her with deference, while the wallclock under the hangings of her lit à la polonaise appears to read noon.

In popular culture

No comments:

Post a Comment