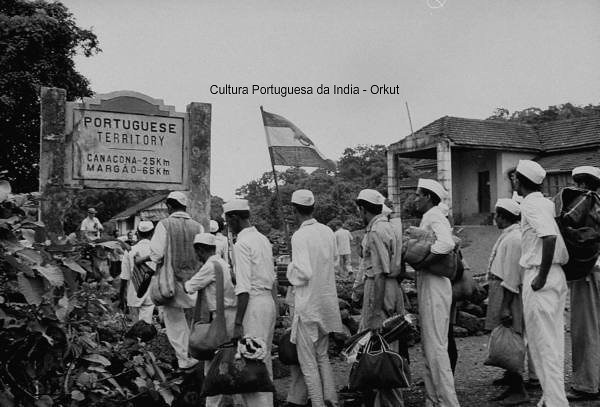

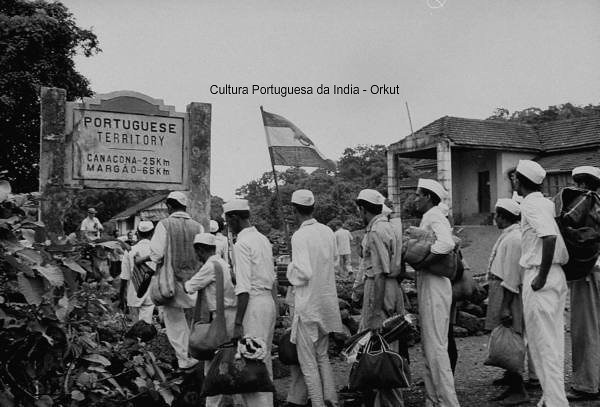

Polem was where Goa ended and India began, as the soil went from brown to red.

When

I first arrived in Polem in 1956, the Portuguese immigration staff was

largely of European origin.

Checks were carried out way beyond sunset,

and if you missed the last bus to Margão

you could sleep in the verandah

of a little restaurant near the check post or under the trees. The

restaurant served xitt-koddi, fried bangdas, tisreos (clams), spicy

xacuti and tender coconut water, along with a host of Portuguese wines –

a small Vinho Porto cost eight tangas (eight annas or fifty paise).

On

two occasions, I carried a bed-sheet and timed my entry into Polem only

for the experience. The leftover passengers made friends easily and

broke into

mandos, music

www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvuFF6eNALI

Nov 17, 2011 - Uploaded by Camilo Fernandes

goan band tidal wave playing portuguese n goan mando..mov .... konkani music at verna summer fete 2012 ...

www.youtube.com/watch?v=GO72ZueZuRM

Aug 20, 2013 - Uploaded by Cidade de Goa

As part of the musical accompaniment, the Mando also saw the East-West ... goan band TIDAL WAVE .

fados music

or English pop, to the accompaniment of a

guitar till late into the night. To keep up with the rising number of

travellers, General Manuel António Vassalo e Silva, the Portuguese

governor general,

visited the post and ordered a spacious shed with

toilets to be built there.

Kaleidoscopic insight to the Mini Portugal,

The passport system

Kaleidoscopic insight to the Mini Portugal,

The passport system

On

the other side of a hillock stood the Indian Customs office, a

British-style building with a trellis frontage. Passenger baggage was

checked in a shed outside the building next to a snack bar that served

tea and samosas, and was frequented by office staff and porters. Those

entering Goa via Karwar

usually ate breakfast before setting out, and

those leaving Goa carried staples like roast pork or

chicken cafreal,

Chicken Cafreal - Goan Cuisine | Cooking with Thas

Chicken Cafreal - Goan Cuisine | Cooking with Thas

pão

and bananas.

The immigration and customs posts stayed open

from 10 am to 6 pm, all through the week. Those whose travel documents

could not be processed had to return to Karwar. But if you were on the

blacklist for being pro-Portuguese, you were deported to Goa regardless

of your documents.

In February 1950, India presented its first

aide-memoire to Portugal to discuss the handover of its territories, but

Portugal replied that their future was non-negotiable. India allowed

for a peaceful Exposition of St Francis Xavier’s relics in Old Goa

from

November 25, 1952 to January 6, 1953. The Bombay State Road Transport

Corporation

was permitted to ply its luxury buses right from the Belgaum

railway station up to Panjim, which had a neat booking office.

But

hardly had the Exposition ended, that Delhi started dispatching

shriller aide-mémoires to Portugal for an immediate handover of its

territories. India shut its legation in Lisbon from June 11, 1953, and

started to mount pressure, both territorially and on Portuguese

Indian-born emigrants working in India. Bombay was host to some 400 Goan

clubs

that provided Goans dormitory accommodation at a pittance. At a

certain stage, these clubs were required by the Bombay Police to

maintain registers under the Foreigners Act, 1946.

Morning You Play Different, Evening You Play Different var _gaq ...

Morning You Play Different, Evening You Play Different var _gaq ...

From October

1953, all Portuguese European officials were required to possess permits

or visas to enter Indian territory; and in February 1954, this rule was

extended to Portuguese officials of Indian origin. On July 31, 1954,

Portugal announced that all Indian citizens entering its

territories would have to possess a passport or an equivalent document,

stamped with a visa from the Portuguese consular authority. India

promptly made it mandatory for Portuguese citizens from the colonies who

were entering the country to have permits from the Indian Consulate

General in Panjim. Those proposing to enter India on Portuguese

passports needed Indian visas, and had to be registered at the nearest

Foreigners Registration Office before getting residential permits.

From

August 1, 1954, the local Portuguese civil administrations of Goa,

Damão and Diu, began issuing a bilingual transit permit, the Documento

Para Viagem to Portuguese citizens travelling to India. The Portuguese

passport and DPV had to be stamped by the district police headquarters

before exiting Portuguese territory. This endorsement was valid for a

week.

Those travelling to Portuguese territories were issued an

Emergency Certificate printed on a sheet of brown paper by the Passport

Office in Bombay. This certificate was valid for a fortnight, though it

invariably expired by the time the Portuguese Consulate General

processed the visa, in consultation with authorities in Goa.

BLOG DE LESTE: 50 ANOS!

BLOG DE LESTE: 50 ANOS!

These are Portuguese India 1952 First Day Cover and Maxim Card of 400th Death Anniversary of Francisco Xavier in my collection.

Routes interrupted

On

August 1, 1954, shipping and road transport services to Goa came to a

halt. A year later, the meter-gauge train that ran from Poona to Goa via

Londa

www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_W12X5J8zo

Dec 19, 2010 - Uploaded by torontochap1

circa 1985, margao train station and bombay to goa train arrival/departure at ... 0-8-0 Loco China old steam ...

www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkeM0yiqoFM

Dec 19, 2010 - Uploaded by torontochap1

... this train at margao railway station headed to vasco terminal, goa. train ... Steam locomotive train ...

also came to a standstill. At Castle Rock

and Collem stations,

passengers were put through immigration checks and their passports and

travel documents were stamped. At Caranzol, the first station in Goa,

I

recall a strapping white Portuguese immigration official with an

automatic rifle strapped to his chest verify my visa on the train with

due courtesy. On arriving in Goa, one of the few objects to be taxed

were playing cards – they were impressed upon by a Portuguese customs

stamp. Foreigners had to report to the district police headquarters in

Goa. As a British citizen, I was graciously assisted by the

Portuguese-speaking regedor of Ucassaim, Chintamani Gaitonde, in

extending my fortnight-long stay in Goa.

Satyagraha

Satyagraha

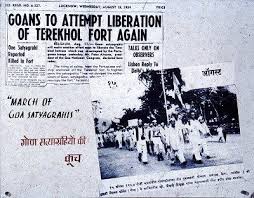

The

August 15, 1954, satyagraha to Goa flopped with barely a hundred Goan

volunteers gate-crashing. But a year later, Delhi aided and abetted a

much more formidable satyagraha of thousands of Indians, hoping that

locals in Goa would rise in revolt. But Goans were of a different psyche

and could not be mob-roused by outsiders who had not realised that the

political scenario in Goa was very different from that in India during

the independence movement. Despite bloodshed, life moved on so

peacefully that Pandit Nehru told the Rajya Sabha on September 7, 1955,

that India was not prepared to tolerate Portuguese presence, even if

Goans wanted them there.

The blockade and a chink

On

August 6, 1955, the Portuguese legation in Delhi was ordered shut and

Portuguese interests were entrusted to the Brazilian Embassy there. On

September 1, 1955, a diplomatic, economic, post and telegraph, and

travel blockade came into effect between India and Portuguese

territories. Mail from Goa to the rest of India was routed via Karachi

in Pakistani mail bags, but mail to Goa was redirected to the sender

even if the address was under-scribed via Karachi, Pakistan. However,

by November 1955, the Universal Postal Union international protocol

prevailed, and censored mail began to move via the southern-most land

posts of Majali and Polem.

Around April 1954, India began issuing

ad-hoc permits on compassionate grounds through the Bombay state

government, regulated by the Ministry of External Affairs’ Goa office in

the Bombay Secretariat. Every applicant had to be interviewed by the

MEA chief, Ashok N Mehta, an Indian Foreign Service officer and

son-in-law of Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit.

My friend, Benito de Sousa,

was bluntly informed by Mehta that he could reach Goa only via Karachi,

as he was a British passport holder. When my turn came, Mehta asked me,

“Do you not know that foreigners are not allowed anywhere near the Goa

border?”

“Yes, I am aware, but I seek this permit on

compassionate grounds,” I replied. “I have to visit my grandmother in

Goa, as my father is tied to his work in Aden.”

“Alright,” said Mehta, “I shall see.”

A

few days after returning to Poona, I was surprised by a brown envelope

affixed with an official service postage stamp. It carried a letter

permitting me to travel to Goa via Majali for a non-specified period.

The Indian overland route permit

Taking

leave of my grandmother, uncle and aunt, I boarded the 10 pm Bangalore

Mail and arrived in Belgaum at around 6 am on May 30, 1956. Within

half-an-hour, I got onto the Bombay State Transport bus to Karwar. It

was a nine-hour journey through winding ghats offering unparalleled

natural vistas, but the journey weighed heavily on my digestive system.

At

Karwar, I was faced with a choice of only two hotels – the posh Sea

Face Hotel and Hotel Rodrigues in the shopping centre. Being low on

cash, I chose the latter and for five rupees got an apology for a room

with sack-cloth walls and a bedful of bugs. The toilet were mercifully

separated from the bathroom.

On the morning of May 30, 1956, I

boarded the bus for Kodibag, carrying a green steel trunk. It was a

45-minute ride through palm-fringed roads lined with pretty cottages.

From Kodibag to Sadashivgad, from where you caught a bus to Majali, was a

creek to negotiate by launch – a rather crude one when compared to

ferries in Goa. After a stopover at Majali village, the bus proceeded to

the immigration post where I was offloaded with a teenage girl and boy.

Both these students had declared in an affidavit that they were moving

to Goa for good.

Portuguese passport for Goans : the "original document" hunt | Goa ...

Portuguese passport for Goans : the "original document" hunt | Goa ...

At the Indian customs post, I was ordered to

surrender my money – 43 rupees, two annas and three pice – against a

receipt valid for four months. If I failed to return before its expiry,

the money would be gifted to the Government of India, they said. Such

perfidy, I fumed. We cooled our heels for 45 minutes till the Indian

immigration officer showed up.

“Did you state in your application

for this permit that you possessed a foreign passport?” he asked,

looking at my British passport.

“Yes,” I replied, handing him a copy of my application.

He

stamped the brown permit, but not the passport. My new found companions

and I walked about two furlongs – over 400 meters – along no-man’s

land. We then went through a gate and stopped at a police check-post

before crossing the international line and entering the Goa Gate in

Polem.

All three of us were bankrupt, and to worsen matters the

fund from which Portuguese border authorities offered five

rupias gratis to every stranded passenger had already been exhausted. So

the uncle of one of my companions loaned me five rupias which I

promised to return, noting his Goa address in my diary.

The same

afternoon, my companions and I boarded the bus to Margão, a two-hour

ride through largely virgin forest and past an impressive temple. At

Canacona, a district police officer stopped the bus and called out my

name. He had been telegraphed by Polém, about the presence of a

foreigner, and after politely checking the entry stamp on my passport,

he allowed us to proceed.

In Margão, I decided to take the

shortest route home to Ucassaim, via the Cortalim-Agaçaim and

Panjim-Betim ferry crossings. I reached Panjim at sunset, emerging a

curiosity with a trunk that belied my journey from India – a rarity

during the blockade. One good soul, who may have gauged that I was cash

strapped – I had only five rupias left – advised me not to buy a

ticket on the ferry, but to claim I had a pass instead.

By the

time I reached Betim, I was left with eight tangas (eight annas) to pay

for my bus ride to Mapuça. As I alighted, a European in a dinner jacket

took leave of those seated beside him, and wished me boa noite (good

night), as was Portuguese etiquette. I hailed a Mercedes Benz taxi. The

tariff was two rupias, but those were days of honesty and no haggling.

When

I reached Ucassaim, it was already 8 pm. I had to bang on the door to

jolt my relatives from their uninterrupted routine. Aunt Vitalina opened

the door to her greatest surprise, for no one had expected me to beat

the blockade and reach home. There were shouts of “Johnnie

ailo! (Johnnie’s arrived)” from the neighbouring family house whose door

had opened at the sound of the taxi. Uncle Alcantara came rushing down

the steps ecstatic, and Aunt Vitalina rushed in to fetch money for the

taxi fare.

The next morning, the Regedor of Ucassaim, Chintamani

Gaitonde, registered my arrival at the district police headquarters, O

Commissariado do Norte, in Mapuça. But because the Brazilian embassy in

Delhi had not specified the permitted duration of my stay in Goa, I had

to also visit the Quartel Geral (Police Headquarters) and Secretariat in

Panjim. The latter affixed revenue stamps of appropriate value on my

passport, and entered a notation on the same page. The stamps were

countersigned by the Director of Civil Administration, Dr. José António

Ismael Gracias.

On my return to Poona on September 20, 1955, the

Portuguese immigration officer at Polém put a saida or exit stamp on my

passport. Walking through no-man’s land, I was back at the Indian

immigration post in Majali where I saw roughly three times as many

people, as on May 30. My money deposited at the Customs was gracefully

refunded, and I boarded the bus for Karwar, where I arrived by sunset

and checked into Hotel Rodrigues for the night.

The next morning,

I boarded the 8 am bus for Belgaum and at two police outposts,

beginning at Karwar’s municipal fringe, we were asked to alight and

details of our permits were registered.

en.wikipedia.org

Permits and etiquette at Polém

en.wikipedia.org

Permits and etiquette at Polém

On

April 3, 1958, India scrapped its permit system, but locals in Goa had

to still produce the Documento para Viagem; those in the rest of India

had to posses a Certificate of Identity. This was in addition to the

visa, a bilingual document in Portuguese and English, issued by the

Brazilian Embassy in Delhi or the Quartel General in Panjim.

Those

entering Goa had to still go through immigration checks at Polém, where

Indian travellers without a health certificate issued by the

municipality were administered anti-cholera and small pox shots; and

travellers could exchange upto 50 Indian rupees for 50 Portuguese

rupias.

The Portuguese post in Polém was far more relaxed than

the Indian one in Majali. In May 1960, my travel companion, an IAF Wing

Commander who hailed from Porvorim, was invited to the Portuguese

military-police canteen in Polém before he could board the bus to

Margão. There was a standing protocol of courtesy when an Indian

military man entered Goa at Polém. On another occasion, a woman who had

lost her baby in Goa while on a visit, was graciously offered

condolences by Portuguese immigration officials, on seeing the child’s

death certificate. But when the same certificate was handed over to

Indian immigration officials at Majali, they were sceptical and put the

mother through some difficult questioning.

Border blacklist

Immigration

staff at Majali had a thick handwritten book, with names of those

considered personae non gratae on the basis of their activities in

India, published writings, official placements in the Government of

Portuguese India or connections with those on the same list. In Bombay,

one never did know who was an informer, and even at a house party it was

a safe bet never to air political views. I once stood behind an Indian

immigration official as he checked my name against the blacklist, and

found an equal number of Hindus and Catholics with remarks against their

names. In January 1959, a family physician from Colaba, Dr. P.N. de

Quadros and his family were debarred from entering India despite valid

travel documents, and had to take a devious jungle route by

country-craft to Bombay. Dr Quadros’ brother had been the President of

the Military Tribunal in Goa, and had sentenced political agitators and

satyagrahis. The same June, a pharma employee, Luis Antonio Chicó, and

his family were detained in Goa for a month despite valid travel

documents, and were allowed to return to Bombay only on the intervention

of influential voices in Delhi. A few months later, a group of Goan

tiatrists led by A.R. Souza Ferrão, and Fr Nelson Mascarenhas, assistant

parish priest of St Francis Xavier’s Church in Dabul, were also

disallowed entry to Majali for a month on their way back from Goa.

It

may surprise young readers to know that Goa had a small airline called

Transportes Aéreos da Índia Portuguesa. It originated in 1954, after the

establishment of airports in Goa, Damão and Diu, and flew tri-weekly.

The Heron aircraft had to be navigated with skill to avoid violating

Indian airspace. After the Indian land permit had been made partially

redundant on April 3, 1958, several Goans took the train to Damaun Road

(renamed Vapi) and tonga to Chaala on the Damão border, to catch a

flight to Goa. Some broke the journey at the Parsi-owned Hotel Britona

in Damão Pequeno (Little Daman).

Last flight

On

October 7, 1961, the Government of Portuguese India issued the

following press note: “The Government of the State of India came to know

through the press of the Indian Union about the decision taken by the

Government to open two more points of passage from her frontier to Goa

via Banda and Anmode. The new points of passage across the frontier

opened by the Indian authorities will contribute to facilitate travel of

Goans to and from the Indian Union. For this reason the decision has

been welcomed by the Government of this State and orders have already

been issued for carrying out the work necessary to open as soon as

possible the frontier of Partadeu via Pernem....”

Jeeps at War on The CJ3B Page

Jeeps at War on The CJ3B Page

cj3b.

Goa, 1954 The city of Goa and the surrounding area on the west coast of India had been a Portuguese ..

The new routes

to Goa were never to be. They turned out to be Delhi’s carefully crafted

ploy to allow the Indian Army access to Goa’s heartland. On November

25, 1961, hostile vessels appeared off the Portuguese island of Angediva

and an Indian fisherman was shot while trying to fend them off.

Goa falls to Indian troops | History Today

Goa falls to Indian troops | History Today

www.historytoday.com

Damaged

Portuguese military vehicles line the route to Panjim Airport, Goa,

December 19th, One of the problems vexing the Indian prime minister

Jawarhalal .

A

few days later, Indian naval ships appeared at the entrance of the

Mormugão harbour, and started to monitor shipping movements. Within a

week, Indian soldiers and armoured vehicles were parked at the frontier.

Placido Rodrigues, a Goan traveller who happened to be at the Majali

post on Sunday, December 17, 1961, was whisked away to safety by the

Indian military, as armoured columns topped up fuel tanks and cranked

their engines en route to Polém.

Operation Vijay Goa 1961 | Attack on Goa by Indian Armed Forces

Operation Vijay Goa 1961 | Attack on Goa by Indian Armed Forces

At 4 am the next day, the Indian army entered Goa, ending 451 years of Portuguese rule

.

Vasco_Da_gama_POW_camp.jpg

The Indian Chief of Army Staff, Gen. Pran Thapar (far right) with

deposed Governor General of Portuguese India Manuel António Vassalo e

Silva (seated centre) at a POW facility in Vasco Da Gama, Goa

Vasco_Da_gama_POW_camp.jpg

The Indian Chief of Army Staff, Gen. Pran Thapar (far right) with

deposed Governor General of Portuguese India Manuel António Vassalo e

Silva (seated centre) at a POW facility in Vasco Da Gama, Goa

happy people of Goa with Indian national flag after liberation from portugal

happy people of Goa with Indian national flag after liberation from portugal

Goa-Invasion-1961: May 2013

Goa-Invasion-1961: May 2013

Gallery - Category: Operation Vijay

Gallery - Category: Operation Vijay

John

Menezes retired as the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Bombay Port

Trust. He lives in the heart of old Bombay, researching and writing

about a city that jogs only in memory.

This is an extract from

John

Menezes retired as the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Bombay Port

Trust. He lives in the heart of old Bombay, researching and writing

about a city that jogs only in memory.

This is an extract from Bomoicar: Stories of Bombay Goans, 1920-1980,

edited and compiled by Reena Martins, Goa,1556. Available via mail-order from goa1556@gmail.com.