Esplanade's glory days, and a certain Mr Watson

Esplanade's glory days, and a certain Mr Watson

By Fiona Fernandez |Posted 07-Jul-2014

Today, as passersby cross the dilapidated Esplanade Mansion at Kala Ghoda, they might probably be unaware that this long-forgotten landmark once played a huge part of India’s grand cinematic and cultural history, and remains a treasure as far as its architectural high points go.

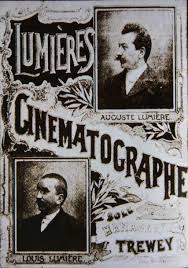

Back in 1896, on this day, Watson’s Hotel, the earlier avatar, was the venue for the first-ever (silent) film screening on the Indian subcontinent by none other than the Lumiere Brothers’ Cinematographe.

This rundown structure remains one of the earliest surviving examples of cast-iron architecture in India. The entire frame of this building was fabricated in England, and was erected on-site between 1867 and 1869.

Named after its first owner,

John Watson, this whites-only hotel was a hit in its glory days with the colonists, and was the place to be seen at and stay at, well before the Taj Mahal Hotel came up at the Apollo Bunder.

Of course, the most popular myth centred on it is that the staff at Watson’s denied entry to

baron Jamsetji Tata,

who decided to build a bigger, better hotel where all were allowed — the iconic

Taj Mahal Hotel.

watson hotel,only for white skins-1870

watson hotel,only for white skins-1870

servers -many were Indians ,other Indians were not allowed

servers -many were Indians ,other Indians were not allowed

Curious, we decided to pore over dusty archived notes on this neglected jewel, only to discover that the man behind it — John Watson was an enterprising and wealthy British merchant, who gave Bombay its first large, luxurious hotel, though its doors were only open to the Europeans.

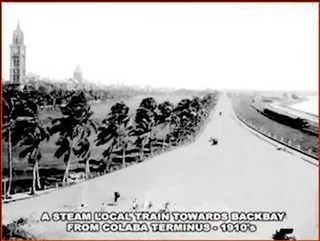

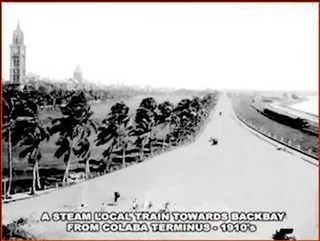

Bombay - The Esplanade and Colaba in

the distance. March 1870 (from the top of Watson's Hotel).--Artist:

Lester, John Frederick (1825-1915)-Date: 1871-

Flora Fountain, built in 1864, is a fusion of water, architecture and sculpture, and depicts the Roman goddess Flora. It was built at a total cost of Rs. 47,000, or 9000 pounds sterling, a princely sum in those days.

VIEW FROM OUTSIDE

The Flora Fountain was erected at the exact place where the Church gate (named after St. Thomas Cathedral, Mumbai ) stood before its demolition along with the Mumbai Fort.The above photo of church gate of fort Bombay -can see the gate,the moat filled with water to prevent enemies(first portuguese and pirates from malabar later Maratha army and

VIEW FROM OUTSIDE

The Flora Fountain was erected at the exact place where the Church gate (named after St. Thomas Cathedral, Mumbai ) stood before its demolition along with the Mumbai Fort.The above photo of church gate of fort Bombay -can see the gate,the moat filled with water to prevent enemies(first portuguese and pirates from malabar later Maratha army and

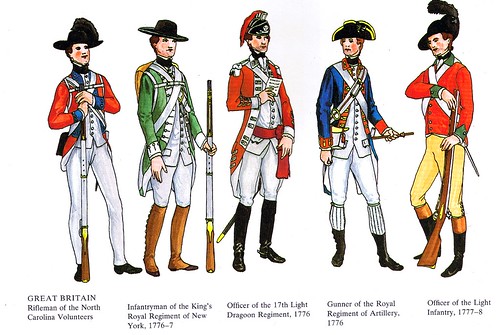

Portuguese soldiers in India 1700's

Portuguese soldiers in India 1700's

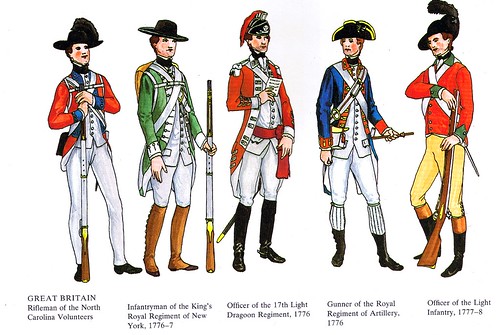

ENGLISH SOLDIERS

for nearly twenty years Bombay lived in fear and trembling. In 1750,

Grose laments that the friendly, or, at worst, harmless belt of

Portuguese territory that used to guard them from the Marathas was gone.

They were face to face with a power, unfriendly at heart, whose

officers were always pressing the government to lead them to Bombay, and

let them raze its wretched fort and pillage its markets

ENGLISH SOLDIERS

for nearly twenty years Bombay lived in fear and trembling. In 1750,

Grose laments that the friendly, or, at worst, harmless belt of

Portuguese territory that used to guard them from the Marathas was gone.

They were face to face with a power, unfriendly at heart, whose

officers were always pressing the government to lead them to Bombay, and

let them raze its wretched fort and pillage its markets

[Grose gives interesting particulars of these terrible Marathas, who had taken Thana and Bassein, and who held Bombay in the hollow of

their hands. Most of them were land-tillers called Kurumbis, of all

shades from deep black to light brown, the hill-men fairer than the

coast-men. They were clean-limbed and straight, some of them muscular

and large bodied, but from their vegetable diet, light, easily overborne

in battle both by Moors and by Europeans. Their features were regular,

even delicate. They shaved the head except the top-knot and two side

curls, which, showing from the helmet, gave them an unmanly look. The

rest of their dress was mean, a roll of coarse muslin round the head, a

bit of cloth round the middle, and a loose mantle on the shoulders also

used as bedding. The officers did not much out figure the men. To look

at, no troops were so despicable. The men lived on rice and water

carried in a leather bottle; the officers fared little better. Their pay

was small, generally in rice, tobacco, salt, or clothes. The horses

were small but hardy, clever in rough roads, and needing little fodder.

The men were armed with indifferent muskets mostly matchlocks. These

they used in bush firing, retreating in haste to the main body when they

had let them off. Their chief trust was in their swords and targets.

Their swords were of admirable temper, and they were trained swordsmen.

European broadswords they held in contempt. Their targets were light

and round, swelling to a point and covered with a lacquer, so smooth

and hard that it would turn aside a pistol shot, even a musket shot at a

little distance. They were amazingly rapid and cunning. The English

would have no chance with them. They might pillage Bombay any day. [Grose's Voyage, I. 83. In spite of this Maratha thunder cloud, Bombay was advancing rapidly to wealth and importance.]

who had taken Thana and Bassein, and who held Bombay in the hollow of

their hands. Most of them were land-tillers called Kurumbis, of all

shades from deep black to light brown, the hill-men fairer than the

coast-men. They were clean-limbed and straight, some of them muscular

and large bodied, but from their vegetable diet, light, easily overborne

in battle both by Moors and by Europeans. Their features were regular,

even delicate. They shaved the head except the top-knot and two side

curls, which, showing from the helmet, gave them an unmanly look. The

rest of their dress was mean, a roll of coarse muslin round the head, a

bit of cloth round the middle, and a loose mantle on the shoulders also

used as bedding. The officers did not much out figure the men. To look

at, no troops were so despicable. The men lived on rice and water

carried in a leather bottle; the officers fared little better. Their pay

was small, generally in rice, tobacco, salt, or clothes. The horses

were small but hardy, clever in rough roads, and needing little fodder.

The men were armed with indifferent muskets mostly matchlocks. These

they used in bush firing, retreating in haste to the main body when they

had let them off. Their chief trust was in their swords and targets.

Their swords were of admirable temper, and they were trained swordsmen.

European broadswords they held in contempt. Their targets were light

and round, swelling to a point and covered with a lacquer, so smooth

and hard that it would turn aside a pistol shot, even a musket shot at a

little distance. They were amazingly rapid and cunning. The English

would have no chance with them. They might pillage Bombay any day. [Grose's Voyage, I. 83. In spite of this Maratha thunder cloud, Bombay was advancing rapidly to wealth and importance.]

Grose, who wrote in 1750, the reasons why the English did not help the

Portuguese were, ' the foul practices' of the Kandra Jesuits against

the English interest in 1720, their remissness in failing to finish the

Thana fort, and the danger of enraging the Marathas, whose conduct of

the war against the Portuguese deeply impressed the English. Voyage, I.

48-51.]

Grose, who wrote in 1750, the reasons why the English did not help the

Portuguese were, ' the foul practices' of the Kandra Jesuits against

the English interest in 1720, their remissness in failing to finish the

Thana fort, and the danger of enraging the Marathas, whose conduct of

the war against the Portuguese deeply impressed the English. Voyage, I.

48-51.]

Except

five churches, four in Bassein and one in Salsette, which the Maratha

general agreed to spare, every trace of Portuguese rule seemed fated to

pass away.

The Portuguese placed their interests in the hands of the English. The

negotiation was entrusted to Captain Inchbird, and though the Marathas

at first demanded Daman and a share in the Goa customs, as well as

Chaul, Inchbird succeeded in satisfying them with Chaul alone. Articles

of peace were signed on the 14th of October 1740 Bombay was little prepared to stand such an attack

as had been made on Bassein. The town wall was only eleven feet high

and could be easily breached by heavy ordnance; there was no ditch, and

the trees and houses in front of the wall offered shelter to an

attacking force

A ditch was promptly begun,

the merchants opening their treasure and subscribing £3000 (Rs.

30,000) ‘ as much as could be expected in the low state of trade’; all

Native troops were forced to take their turn at the work; gentlemen and

civilians were provided with arms and encouraged to learn their use;

half-castes or topazes were enlisted and their pay was raised; the

embodying of a battalion of sepoys was discussed; and the costly and

long-delayed work of clearing of its houses and trees a broad space

round the town walls was begun. Though the Marathas scoffed at it,

threatening to fill it with their slippers, it was the ditch that saved

Bombay from attack.

A ditch was promptly begun,

the merchants opening their treasure and subscribing £3000 (Rs.

30,000) ‘ as much as could be expected in the low state of trade’; all

Native troops were forced to take their turn at the work; gentlemen and

civilians were provided with arms and encouraged to learn their use;

half-castes or topazes were enlisted and their pay was raised; the

embodying of a battalion of sepoys was discussed; and the costly and

long-delayed work of clearing of its houses and trees a broad space

round the town walls was begun. Though the Marathas scoffed at it,

threatening to fill it with their slippers, it was the ditch that saved

Bombay from attack.

mumbaireadyreckoner.org/.../history-of-bombay-city1670-onwards-und...

Sep 5, 2011 - Weavers came from Chaul to Bombay, and a street was ordered to be built ...... It was open to attack from the Sidi, the English, or the Marathas.

for nearly twenty years Bombay lived in fear and trembling.

Kanhoji Angre'S FLEET OF MARATHA WAR SHIPS

Kanhoji Angre'S FLEET OF MARATHA WAR SHIPS

The Fort, Bombay, Harbour face wall,- 1863.--Date: 1863--Photographer: Unknown

GUNS POINTING DOWN INTO MOAT

Watson owned a drapery store south of Churchgate Street,

Watson owned a drapery store south of Churchgate Street,

and successfully out-bidded others in securing prime land at the Esplanade. He designed and built Watson’s without any chief architect, using red stone plinth, while the bases for the columns and the plinth came directly from Penrith in Cumberland, UK. He even brought down maids, waiters and waitresses from England to ensure the memsahibs and officers didn’t get homesick.

Church Gate Street of bombay fort , --(and Times of India office).Photographer: Unknown Medium: Photographic print Date: 1860

{VIEW FROM INSIDE BOMBAY FORT ,BEFORE DEMOLITION OF FORT WALLS AND GATES}

This

view of Churchgate Street, now known as Vir Nariman Road, in the Fort

area of Bombay was taken in the 1860s to form part of an album entitled

'Photographs of India and Overland Route'. Churchgate Street runs from

Horniman Circle at the east end to what was originally named Marine

Drive at the edge of the Back Bay. Churchgate Station, the old General

Post Office (now the Telegraph Office) and the Cathedral Church of St

Thomas, the oldest still-functioning structure in the city, are all

located along its length. However, Churchgate Station and the Post

Office were later additions to the street and would not have been in

existence at the time of this photograph.

In fact, hard as it might be to imagine today, Watson’s served as a landmark in its time for ships entering the harbour! There’s more, too. One of the hotel’s most popular guests was Mark Twain,

who went on to write about the crows he saw from his balcony in Following the Equator.

By the 1960s, the hotel had to close down and was partitioned into tiny cubicles that were rented out. Today, this 83,000-sq ft property, believed to be valued at Rs 450 crore, waits to be restored and redeveloped entirely, and one hopes, to its past glory, as reported by mid-day in July 2013.

To sign off, here’s a poignant observation crafted by the great Twain, while on a night stroll during that stay-in, in 1896, “…everywhere on the ground lay sleeping natures hundreds and hundreds. They lay stretched at full length and tightly wrapped in blankets heads and all. Their attitude and rigidity counterfeited death.”

The writer is Features Editor of mid-day

7/7/1896: India's First

Screening

In early July 1896,

The Times of India ran an advertisement proclaiming the arrival of “the

marvel of the century” and “wonder of the world” at the elite

Watson’s Hotel in Bombay, while the nearby Madras Photographic Stores

carried a more modest advertisement for ‘animated photographs’. On the evening

of the 7th,

Marius

Sestier, an agent for the

Lumieres, held four screenings at the hotel, each of them with an admission

charge of one rupee. The audience, which largely comprised of British

officials marvelled at such films as

Arrivee

d’un Train en Gare,

The Sea

Bath,

A

Demolition, and

La

Sortie des Usines Lumiere.

Sestier

was also charged with shooting scenes of Indian life, but unfortunately his

skills behind the camera were sadly lacking, and the films he sent back to Paris

were rejected as ‘incompetent’, thus explaining the dearth of Indian films in

the

Lumiere catalogue of the time.

Further screenings

took place for the ‘natives’ at the

Novelty

Theatre – the former home of the Victoria Theatre Company – in Bombay on the

14th July.

[ADD]

Further Reading:

www.youtube.com/watch?v=d_9N68MO9gM

Jan 7, 2013 - Uploaded by Cinema History

Contrary to myth, it was not shown at the Lumières' first public film ... in his essay, "Lumiere's Arrival of the ...

1896

The

142-year-old building in Kala Ghoda stands out like a sore thumb in the

line of magnificent heritage structures in Kala Ghoda - See more at:

http://www.mid-day.com/articles/esplanade-mansion-95-safe-or-100-unsafe/218256#sthash.i7R7tpRy.dpuf

142 year old building now [land sharks waiting -if politicians hand it over ]

three balconies collapsed in 2005{benign govt:neglect ?for builders sake?]

The

142-year-old building in Kala Ghoda stands out like a sore thumb in the

line of magnificent heritage structures in Kala Ghoda

The

142-year-old building in Kala Ghoda stands out like a sore thumb in the

line of magnificent heritage structures in Kala Ghoda - See more at: http://www.mid-day.com/articles/esplanade-mansion-95-safe-or-100-unsafe/218256#sthash.i7R7tpRy.dpuf

The

142-year-old building in Kala Ghoda stands out like a sore thumb in the

line of magnificent heritage structures in Kala Ghoda

The

142-year-old building in Kala Ghoda stands out like a sore thumb in the

line of magnificent heritage structures in Kala Ghoda - See more at: http://www.mid-day.com/articles/esplanade-mansion-95-safe-or-100-unsafe/218256#sthash.i7R7tpRy.dpuf