Painting Of Watson's Esplanade Hotel - Castle Carrock

www.castlecarrock.com

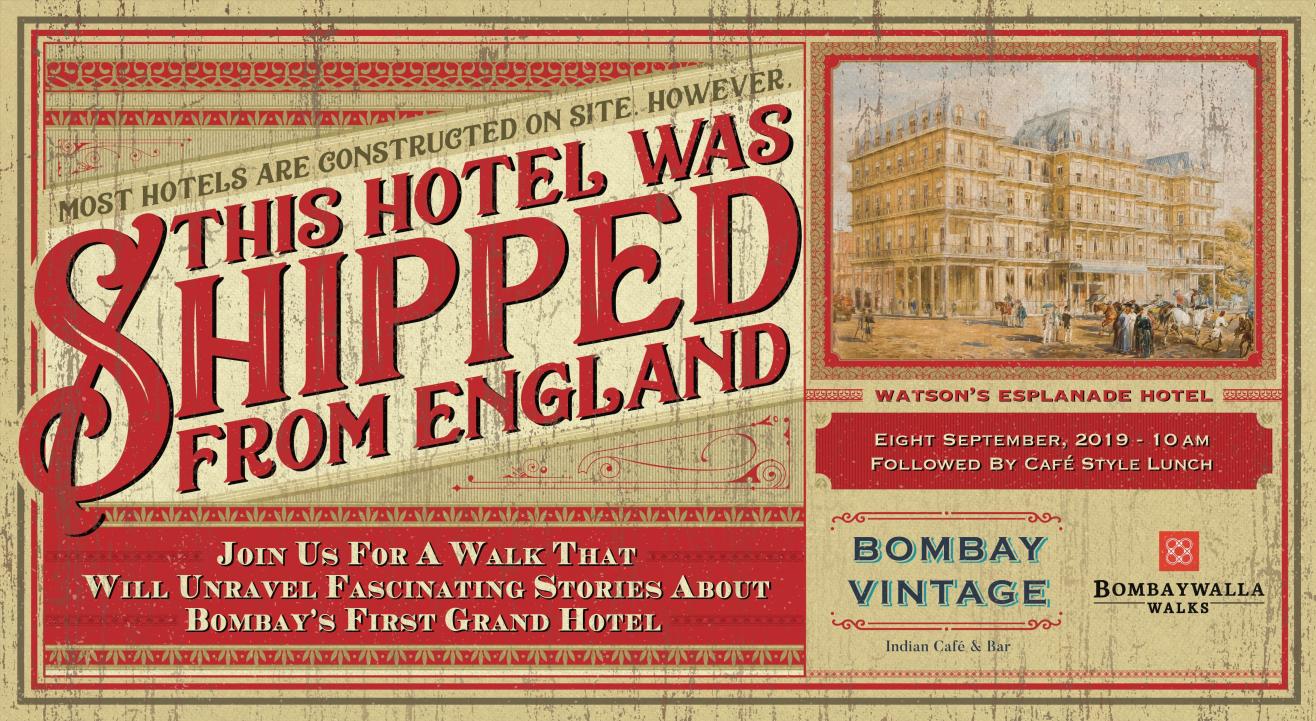

WATSON'S ESPLANADE HOTEL

..

This

magnificent painting of a sumptuous building in foreign lands hangs on

one end wall of the Watson Institute, now the village hall, in Castle

Carrock. It’s approximately 200cm by 100cm in size. And it bears

testimony to a remarkable story connecting the man who built the

Institute with the building it portrays. Long a decaying, crumbling mass

of iron and brick, and now known as “Esplanade Mansions”, the remains

that are still left to see barely evoke the grandeur they once enjoyed

as Bombay’s premier nineteenth century hotel.

So what’s so special about the building ?

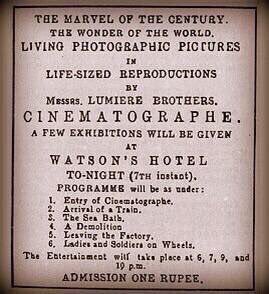

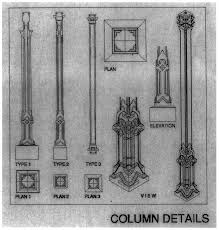

Its design is unique because of its prefabricated and blatantly outward facing iron skeleton and its accompanying brick non load bearing insertions. It eschewed a traditional style for a direct expression of structure. For this reason, it can even be said to take its rightful place in the story of the evolution of the skyscraper. And it was unquestionably the first multi-storey habitable building in the world in which all loads, including those of the brick curtain walls, are carried on an iron frame. Like the Crystal Palace of 1851, it’s a landmark in the development of this type of design construction. Prior to similar buildings being constructed in Chicago in the 1880s, all other fully framed multi-storey buildings were built to serve the needs of exhibitions, industry or storage. Watson’s was built for habitation, and as such provided for bathing and ventilation, as well as internal transportation, including reputably housing India’s first power operated elevator.

And what of the connection with Castle Carrock ?

John Hudson Watson was born in 1818 in Castle Carrock. He was the first son of John Watson (1790-1880), a yeoman farmer, and his wife Jane Hudson (c1783-1826). John spent his childhood in the village along with his siblings Margaret (b.1817), Peggy (1820), William (1822) and Joseph (1826). John Hudson Watson may have continued the family farming tradition in his early working life but in the 1840s after getting married to Hannah Proctor, he moved with his brother William to London to set up a drapery business. In 1853, the two Watson brothers emigrated to Bombay and in 1856, two of John and Hannah’s children, James Proctor (1843-1923) and John jnr joined the firm as assistants. The business flourished. And ambition grew.

The first auction of plots on the Esplanade in Bombay took place in August 1864 and was attended by John Hudson Watson. He had some competition for his plans for lot Nos 11 and 12 but won through. He already had a shop close by – he was a silk mercer, draper and hosier and had already amassed a large fortune. Over the next few years, the development of public and private buildings in Bombay took place on a massive scale. John Hudson Watson’s original plan was not for a hotel but for additional office and showroom facilities for his thriving drapery and tailoring businesses down the road.

=============================================

“…why is it that the ugliest of all ugly and ill-conceived buildings should be allowed to push its misbegotten meaningless front (in which the only thought displayed is in the construction and connection of cast iron work) far in advance of all its neighbours…looking like an iron construction always does, as temporary makeshift, without the one advantage of its being so ?”

“Messrs Watson and Co’s gigantic iron structure cannot fail to impress one as an excessively unsightly building – at present it is an absolute eye-sore; as to what it may be eventually when its skeleton form is draped, I know not, but it looks now as if corrugated iron would well suit it.”

An image of the building under construction appeared in “The Architect” in December 1869. Watson came under pressure to complete the building within a government imposed two year deadline. He successfully applied for an extension and he himself had taken up residence by the autumn of 1870 as the interior was being fitted out around him. The hotel was finally opened on 4th February 1871.

The original design, as displayed on the painting in the Institute, included plans for a more showy mansard roof – it was never built. Plans were altered by Ordish in 1867. And photographs of the day show a much flatter roof was installed.

The Bombay Gazette proclaimed it as

“without doubt the finest hotel in the city…built at enormous cost….on

perhaps the best site in Bombay”.

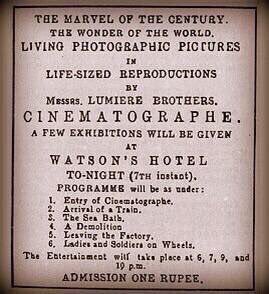

John Hudson Watson’s brother, left the drapery business in 1867 to become a shipping agent in Bombay. It thrived for many years until liquidation in 1904. It was thus James Proctor Watson and John Watson jnr who oversaw the drapery and hotel business on the death of their father. Watson’s Esplanade Hotel enjoyed a period of unrivalled splendour. It was patronised by notable and distinguished guests, even being fictionalised in two of Rudyard Kipling’s stories. Mumbai continued to grow as a trading centre through the second half of the 19th century. Trams came in 1874 and electricity in 1882. Like all successful businesses, Watson’s kept apace with the times. In 1882, it went for a major facelift, adding a hydraulic lift “such as one finds in the large buildings in England” and a bar that “reminds one strongly of the bars in London restaurants” as well as electric lights and bells. The restaurant and bar employed only English waitresses; European stewards and stewardesses kept rooms in a “state of thorough cleanliness”. Soon after, it made film history. On July 7th 1896, the hotel offered screenings, to Europeans at the cost of one rupee each, of some of the Lumiere Brothers first films, including the Entry of Cinematographe,

Arrival Of A Train,

=============================================

mumbai-magic.blogspot.com

The Watson brothers began to ship materials for the new building into

Mumbai. By 1867, many of the materials had arrived; and assembly of the

iron framework began on site. By 1869, the hotel was complete - BUT -

that beautiful (and impractical) mansard was abandoned along the way.

Maybe they ran out of money - or time.

Still, just look at this hotel below! What views of Bombay harbour! This

photo is from the 1880s; the only other building at that time in the

area was the Sailors' Home in the distance. The wide road you see is the

Esplanade; and hence the name of the hotel.

The patch of land on the right of the photo, by the sea, is where the

Taj Mahal Palace and Towers eventually came up - but that was not until

1903. Before that, for more than 30 years, Watsons Hotel was the numero

uno establishment in the city. Mark Twain stayed here; Kipling wrote

about it, and the earliest screening of the Cinematographe in India by

the Lumiere Brothers was in this hotel (just one week after it was first

screened in Paris).

Of the two brothers, John and William Watson, we know this: William quit the drapery business to become a shipping agent. John Watson remained in the drapery and hotel business; but he returned to the village of Castle Carrock in 1869, just after Watsons Hotel was built. His sons, James Proctor and John Jr, inherited and ran the hotel successfully, until they too returned to Cumbria in 1896 (at the time of Bombay's bubonic plague).

With the owners gone, and with competition from new hotels such as Green's, Majestic, and the Taj, the birdcage hotel went into decline. In 2006, the World Monument Fund placed the hotel under the list of World Endangered Monuments.

Here's a recent photo I clicked; can you see the beautiful Minton floor tiling? The iron girders are still standing strong. The inside of the hotel has been divided up and sub-let to lots of small businesses. Next time you're in the area, pop into the building and take a quick look. And if you want a little challenge, then try to spot the Watsons logo on the outside of the building!===========================================

==============================================

===============================================

..

Watson's Esplanade Hotel | © Castle Carrock / WikiCommons

Painting Of Watson’s Esplanade Hotel

Why Is This Painting Of Watson’s Esplanade Hotel, In Mumbai (Bombay), Hanging In The Watson Institute?

WATSON’S ESPLANADE HOTEL IN MUMBAI (BOMBAY)

So what’s so special about the building ?

Its design is unique because of its prefabricated and blatantly outward facing iron skeleton and its accompanying brick non load bearing insertions. It eschewed a traditional style for a direct expression of structure. For this reason, it can even be said to take its rightful place in the story of the evolution of the skyscraper. And it was unquestionably the first multi-storey habitable building in the world in which all loads, including those of the brick curtain walls, are carried on an iron frame. Like the Crystal Palace of 1851, it’s a landmark in the development of this type of design construction. Prior to similar buildings being constructed in Chicago in the 1880s, all other fully framed multi-storey buildings were built to serve the needs of exhibitions, industry or storage. Watson’s was built for habitation, and as such provided for bathing and ventilation, as well as internal transportation, including reputably housing India’s first power operated elevator.

And what of the connection with Castle Carrock ?

John Hudson Watson was born in 1818 in Castle Carrock. He was the first son of John Watson (1790-1880), a yeoman farmer, and his wife Jane Hudson (c1783-1826). John spent his childhood in the village along with his siblings Margaret (b.1817), Peggy (1820), William (1822) and Joseph (1826). John Hudson Watson may have continued the family farming tradition in his early working life but in the 1840s after getting married to Hannah Proctor, he moved with his brother William to London to set up a drapery business. In 1853, the two Watson brothers emigrated to Bombay and in 1856, two of John and Hannah’s children, James Proctor (1843-1923) and John jnr joined the firm as assistants. The business flourished. And ambition grew.

The first auction of plots on the Esplanade in Bombay took place in August 1864 and was attended by John Hudson Watson. He had some competition for his plans for lot Nos 11 and 12 but won through. He already had a shop close by – he was a silk mercer, draper and hosier and had already amassed a large fortune. Over the next few years, the development of public and private buildings in Bombay took place on a massive scale. John Hudson Watson’s original plan was not for a hotel but for additional office and showroom facilities for his thriving drapery and tailoring businesses down the road.

=============================================

“…why is it that the ugliest of all ugly and ill-conceived buildings should be allowed to push its misbegotten meaningless front (in which the only thought displayed is in the construction and connection of cast iron work) far in advance of all its neighbours…looking like an iron construction always does, as temporary makeshift, without the one advantage of its being so ?”

“Messrs Watson and Co’s gigantic iron structure cannot fail to impress one as an excessively unsightly building – at present it is an absolute eye-sore; as to what it may be eventually when its skeleton form is draped, I know not, but it looks now as if corrugated iron would well suit it.”

An image of the building under construction appeared in “The Architect” in December 1869. Watson came under pressure to complete the building within a government imposed two year deadline. He successfully applied for an extension and he himself had taken up residence by the autumn of 1870 as the interior was being fitted out around him. The hotel was finally opened on 4th February 1871.

The original design, as displayed on the painting in the Institute, included plans for a more showy mansard roof – it was never built. Plans were altered by Ordish in 1867. And photographs of the day show a much flatter roof was installed.

It

boasted a sumptuous, top lit ground floor restaurant with attached

billiard room, a first floor dining saloon (with another attached

billiards room), and three upper storeys given over to 131 bedrooms and

apartments, the uppermost of which were reserved for “bachelors and

quasi single gentlemen”. With over 120 baths fitted, it outdid European

levels of luxury. It was thoroughly ventilated throughout with a punkah

wallah (type of fan) serving every room and it commanded breathtaking

views across the harbours, bays and distant hills – and it boasted

India’s first steam powered lift.

m

1606 × 1684

1606 × 1684

The whole accent was on showy shops, dining halls and the drawing and billiard rooms. By contrast, the private, upper part of the building was a maze of small rooms served by narrow corridors, with room heights decreasing as you went further up – 20ft on the ground floor to 14ft on the third and fourth. Clearly, Watson wanted to extract as much profit as he could from the building, cramming in as many guests as possible, yet appeasing them with fine European cuisine and sumptuous social spaces where they could mix with Bombay’s resident British elite.

Yet

John Hudson Watson may never have witnessed his hotel’s formal opening

in February 1871. He had had built Gelt Hall, the grandest house in

Castle Carrock, in 1863. And some time in 1869 or 1870 he returned to

England and took up residence back in London. The move back may have

been prompted by failing health. He died in May 1871. His wife died 4

years later. Both lie buried at St Peters church in Castle Carrock.

m

The whole accent was on showy shops, dining halls and the drawing and billiard rooms. By contrast, the private, upper part of the building was a maze of small rooms served by narrow corridors, with room heights decreasing as you went further up – 20ft on the ground floor to 14ft on the third and fourth. Clearly, Watson wanted to extract as much profit as he could from the building, cramming in as many guests as possible, yet appeasing them with fine European cuisine and sumptuous social spaces where they could mix with Bombay’s resident British elite.

The hotel was an enormous success in its early years.

An

advertisement, five months after its opening, lists foods, wines and

other exotic items like French percolators for making coffee, bottled

fruits like gooseberries and rhubarbs, and even “Figured Moguls” playing

cards for sale. In today’s parlance, it was the first five star hotel

of Bombay and soon became the place to hang out if you were European.

“The ball at Watson’s hotel on Monday was, we are informed, a great

success… an excellent band was engaged for the occasion, and dancing was

kept up until an early hour,” recorded the Times of India on August 7,

1871.

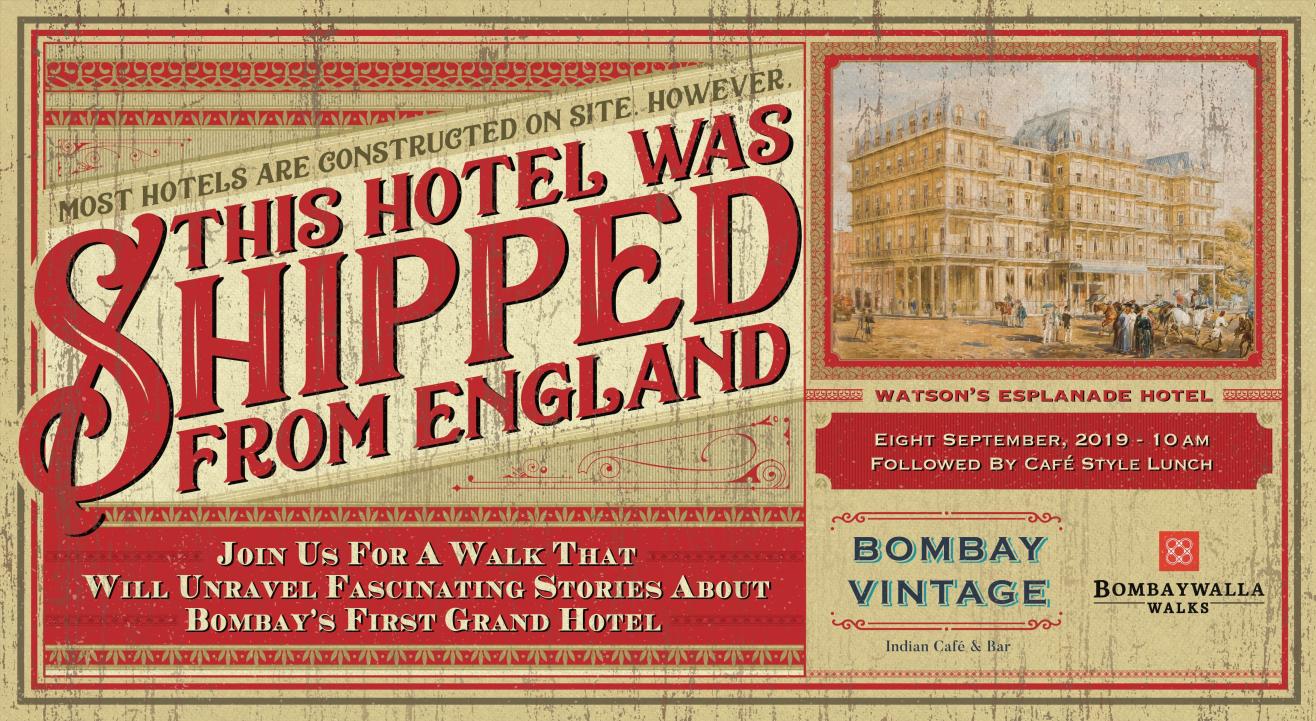

John Hudson Watson’s brother, left the drapery business in 1867 to become a shipping agent in Bombay. It thrived for many years until liquidation in 1904. It was thus James Proctor Watson and John Watson jnr who oversaw the drapery and hotel business on the death of their father. Watson’s Esplanade Hotel enjoyed a period of unrivalled splendour. It was patronised by notable and distinguished guests, even being fictionalised in two of Rudyard Kipling’s stories. Mumbai continued to grow as a trading centre through the second half of the 19th century. Trams came in 1874 and electricity in 1882. Like all successful businesses, Watson’s kept apace with the times. In 1882, it went for a major facelift, adding a hydraulic lift “such as one finds in the large buildings in England” and a bar that “reminds one strongly of the bars in London restaurants” as well as electric lights and bells. The restaurant and bar employed only English waitresses; European stewards and stewardesses kept rooms in a “state of thorough cleanliness”. Soon after, it made film history. On July 7th 1896, the hotel offered screenings, to Europeans at the cost of one rupee each, of some of the Lumiere Brothers first films, including the Entry of Cinematographe,

Arrival Of A Train,

Arrival of a Train at La Ciotat (The Lumière ... - YouTube

www.youtube.com/watch?v=1dgLEDdFddk

May 27, 2006 - Uploaded by raphaeldpm

Original Title: L'Arrivée d'un Train à la Ciotat Directors: Auguste and Louis Lumière Year: 1895 The first ...

The Sea Bath,

The Sea (1895) Louis Lumière - YouTube

www.youtube.com/watch?v=jm9rI_gZTqE

Dec 22, 2012 - Uploaded by silentfilmhouse

In this early silent film five men jump into stormy weather from a dock, swim to shore and repeat the process ...

A Demolition,

Leaving The Factory

This was India’s first taste of the moving image, just 6 months after their Paris debut.

On July 7th 1896 the Lumiere Brothers showcased six films at the Watson ... Arrival of a Train, A Demolition, Ladies and Soldiers on Wheels and Leaving the

1896 was a good year for Watson’s and a bad year for India. A famine which began in the early months of that year killed millions. Bombay was hit by a bubonic plague epidemic in September, which also killed thousands of people. But within the cool confines of the Watson’s, things couldn’t be better. In February that year, American novelist Mark Twain visited India and stayed at Watson’s. In a chapter in his book Following the Equator, Twain describes the scene at Watson’s. “The lobbies and halls were full of turbaned, and fez’d and embroidered, cap”d, and barefooted, and cotton-clad dark natives … in the dining room every man’s own private native servant standing behind his chair, and dressed for a part in Arabian Nights.”

But just a few years later, things began to look less certain for the hotel.

The turn of the century saw the appearance of a new breed of larger, grander establishments, reflecting civic improvement. The Taj Mahal hotel opened with 400 rooms in 1903 with attractions like electric lifts, lights, bars, smoking rooms and a hotel orchestra. A popular myth is that J N Tata built the Taj after he was denied entry to Watson’s. Whatever the stories, this sort of competition spelled the death-knell for the Watsons’ hotel venture. By 1911, Watson’s with its garishly painted exterior was savaged by the Times of India: “Their majesties (King George V) will have to pass what we can only suppose is an experiment in garishness, Watson’s Hotel, and that building is a good illustration of the dangers to which a sensitive public is exposed.”

The hotel’s decline was gradual, but stark. And by 1920, Watson’s had ceased to be a hotel. It had been renamed Mahendra Mansion and then in 1944, it was renamed Esplanade Mansion.

In 1960 it was converted into housing and offices accommodating, in 2005, 53 families and 97 commercial premises.

Eleven years ago, after 132 years of use and abuse, this designedly permanent prefabricated wonder still stood wholly on the frame action of its rigid column beam connections. Ample testimony to the Phoenix Foundry Company’s fabrication and assembly skills and Rowland Mason Ordish’s adroit structural design. The first person to draw real attention to its structural interest was Christopher London. He was certainly the first modern commentator to ascribe correctly the design to Ordish (and not John Watson), noting the engineer’s links to the Crystal Palace. Subsequently, many other architectural historians took time to record their admiration for the historical significance and innovation of the design.

Part of the building collapsed in 2005, killing one person. Today, all that is left of Watson’s heydays is its magnificent iron pillars, frame and wooden staircase. Everything else has been broken up into small rooms, which have been rented out to tailors, photocopy shops and lawyers. Why not tear it down ? Conservation architects say it is India’s oldest cast iron building and is a crucial part of Mumbai’s architectural heritage. Just a few years ago, it was placed on the list of the “100 World Endangered Monuments”.

And so, back to the painting.

James Proctor Watson – the son of John Hudson Watson who had built the hotel – and his wife Clara had returned to Castle Carrock from Bombay in 1896, taking up residence at Garth Marr. The following year, he built the Watson Institute, described in Bulmer’s History & Directory of Cumberland published in 1901, as being a “fine block of red sandstone buildings consisting of a public hall, free library and reading room, erected at a cost of £1,500″. He donated 700 volumes to the library, with papers and periodicals coming from Lady Carlisle. The hall was soon busy with dances, billiards and concerts – as well as no doubt, some reading.

And so we come full circle. In honour of his father, James commissioned the painting to mark the existence of his family’s glamorous hotel, dreamt up by his father John, to be hung in the Watson Institute. And it was he who wrote the inscription at the image’s base, which reads:

“This building was designed in London for John Watson of Gelt Hall by Messrs Ordish and Le Febre. The materials for this were wholly English; the iron frame from Derby, the bricks and cement from the bank of the Thames, the tiles from Staffordshire, and finally the red stone plinth and column bases from Penrith.”

Castle Carrock has a village hall which looks a bit like a Castle. When it was built in 1898 it was known as The Watson Institute

and had a free library. Since then it has changed hands and there is no

longer a library there, but it is still used for many things. The

changing hands has led to some debate amongst the villages as to whether

it is called the Watson Institute or the Watson Hall. It no longer has a

library, so hall makes more sense to some. To others it is institute

because it always was and always will be. By whichever name you choose

to give our rather interesting looking village meeting space, it is used

much throughout the year for a variety of public and private events and

is the centre of many village goings on.

Castle Carrock has a village hall which looks a bit like a Castle. When it was built in 1898 it was known as The Watson Institute

and had a free library. Since then it has changed hands and there is no

longer a library there, but it is still used for many things. The

changing hands has led to some debate amongst the villages as to whether

it is called the Watson Institute or the Watson Hall. It no longer has a

library, so hall makes more sense to some. To others it is institute

because it always was and always will be. By whichever name you choose

to give our rather interesting looking village meeting space, it is used

much throughout the year for a variety of public and private events and

is the centre of many village goings on.

We’re very sorry, unfortunately there is no longer a castle in Castle

Carrock. Many years ago there was once either a very large mansion or

castle here which was owned by Robert de Castle Carrock. It was taken

down and it is believed that some of the stone was then used to rebuild

St. Peter’s Church. Castle Carrock is a thriving little community

village with a shop, primary school, pub, village hall and a church.

We’re very sorry, unfortunately there is no longer a castle in Castle

Carrock. Many years ago there was once either a very large mansion or

castle here which was owned by Robert de Castle Carrock. It was taken

down and it is believed that some of the stone was then used to rebuild

St. Peter’s Church. Castle Carrock is a thriving little community

village with a shop, primary school, pub, village hall and a church.

Also Castle Carrock has a reservoir, which is something of a local landmark and an excellent place to go for a walk. Back in the 1980s BBC Radio 4 did a short series about life in a typical country village. Castle Carrock was chosen as the said typical village, you can listen to the recordings of the show on this website.

=============================================

Thanks to Nergish Sunavala of the Times of India newspaper for the new photos.

Tom Speight, Chair of the Watson Institute, September 2013

Auguste & Louis Lumière: Demolition of a Wall (1896 ...

www.youtube.com/watch?v=li5pDJ2MqPU

Oct 19, 2009 - Uploaded by iconauta

Auguste & Louis Lumière: Demolition of a Wall (1896). iconauta ... Breve Storia del Cinema - Il ...Leaving The Factory

1895, Lumiere, Workers Leaving the Lumiere Factory (1895 ...

www.youtube.com/watch?v=DEQeIRLxaM4

Feb 8, 2011 - Uploaded by MediaFilmProfessor

La sortie des usines Lumière (three different versions) Movies for mass public consumption are considered to be ... and

Ladies And Soldiers On Wheels. Discovery of Film Camera : Paris to Bombay - YouTube

www.youtube.com/watch?v=kbsYlLG-sAc

Mar 29, 2013 - Uploaded by Satyaprakash Gupta

The Lumiere cinematograph was the culmination of long journey that ... Demolition,Leaving the factory and ...This was India’s first taste of the moving image, just 6 months after their Paris debut.

July 7th 1896 - Indian Cinema is Born - Maps of India

www.mapsofindia.com › On this Day

1896 was a good year for Watson’s and a bad year for India. A famine which began in the early months of that year killed millions. Bombay was hit by a bubonic plague epidemic in September, which also killed thousands of people. But within the cool confines of the Watson’s, things couldn’t be better. In February that year, American novelist Mark Twain visited India and stayed at Watson’s. In a chapter in his book Following the Equator, Twain describes the scene at Watson’s. “The lobbies and halls were full of turbaned, and fez’d and embroidered, cap”d, and barefooted, and cotton-clad dark natives … in the dining room every man’s own private native servant standing behind his chair, and dressed for a part in Arabian Nights.”

But just a few years later, things began to look less certain for the hotel.

The turn of the century saw the appearance of a new breed of larger, grander establishments, reflecting civic improvement. The Taj Mahal hotel opened with 400 rooms in 1903 with attractions like electric lifts, lights, bars, smoking rooms and a hotel orchestra. A popular myth is that J N Tata built the Taj after he was denied entry to Watson’s. Whatever the stories, this sort of competition spelled the death-knell for the Watsons’ hotel venture. By 1911, Watson’s with its garishly painted exterior was savaged by the Times of India: “Their majesties (King George V) will have to pass what we can only suppose is an experiment in garishness, Watson’s Hotel, and that building is a good illustration of the dangers to which a sensitive public is exposed.”

The hotel’s decline was gradual, but stark. And by 1920, Watson’s had ceased to be a hotel. It had been renamed Mahendra Mansion and then in 1944, it was renamed Esplanade Mansion.

In 1960 it was converted into housing and offices accommodating, in 2005, 53 families and 97 commercial premises.

Eleven years ago, after 132 years of use and abuse, this designedly permanent prefabricated wonder still stood wholly on the frame action of its rigid column beam connections. Ample testimony to the Phoenix Foundry Company’s fabrication and assembly skills and Rowland Mason Ordish’s adroit structural design. The first person to draw real attention to its structural interest was Christopher London. He was certainly the first modern commentator to ascribe correctly the design to Ordish (and not John Watson), noting the engineer’s links to the Crystal Palace. Subsequently, many other architectural historians took time to record their admiration for the historical significance and innovation of the design.

Part of the building collapsed in 2005, killing one person. Today, all that is left of Watson’s heydays is its magnificent iron pillars, frame and wooden staircase. Everything else has been broken up into small rooms, which have been rented out to tailors, photocopy shops and lawyers. Why not tear it down ? Conservation architects say it is India’s oldest cast iron building and is a crucial part of Mumbai’s architectural heritage. Just a few years ago, it was placed on the list of the “100 World Endangered Monuments”.

James Proctor Watson – the son of John Hudson Watson who had built the hotel – and his wife Clara had returned to Castle Carrock from Bombay in 1896, taking up residence at Garth Marr. The following year, he built the Watson Institute, described in Bulmer’s History & Directory of Cumberland published in 1901, as being a “fine block of red sandstone buildings consisting of a public hall, free library and reading room, erected at a cost of £1,500″. He donated 700 volumes to the library, with papers and periodicals coming from Lady Carlisle. The hall was soon busy with dances, billiards and concerts – as well as no doubt, some reading.

And so we come full circle. In honour of his father, James commissioned the painting to mark the existence of his family’s glamorous hotel, dreamt up by his father John, to be hung in the Watson Institute. And it was he who wrote the inscription at the image’s base, which reads:

“This building was designed in London for John Watson of Gelt Hall by Messrs Ordish and Le Febre. The materials for this were wholly English; the iron frame from Derby, the bricks and cement from the bank of the Thames, the tiles from Staffordshire, and finally the red stone plinth and column bases from Penrith.”

The building in September 2014

Watson Institute

About Castle Carrock

Also Castle Carrock has a reservoir, which is something of a local landmark and an excellent place to go for a walk. Back in the 1980s BBC Radio 4 did a short series about life in a typical country village. Castle Carrock was chosen as the said typical village, you can listen to the recordings of the show on this website.

- Castle Carrock

- Castle Carrock is a village and civil parish on the B6413 road, in the City of Carlisle District, in the English county of Cumbria about 3 miles south of Brampton. It has a pub, a primary school and many walks. Wikipedia

Tom Speight, Chair of the Watson Institute, September 2013

Find Out More

mumbai-magic.blogspot.com

Here is what this building was originally meant to be. See how gorgeous

it looks in this painting! (If you click on the picture, you'll get a

bigger view).

|

| Photo credit: Castle Carrock |

If you want to see this painting for real, you have to travel to Cumbria, to a little green village called Castle

Carrock. The painting of Esplanade Mansions is hanging in

their town hall. Here's what the village of Castle Carrock looks like; it has less than 500 people living in it.

|

| Photo credit: Castle Carrock |

The story of Esplanade Mansions actually begins in this little village.

Like many good stories, this one also begins with a farmer :) His name

was Watson.

The farmer had three sons, but two of them, John and William Watson, left Castle Carrock in the 1840's to start a drapery business in London, dealing in silks and other textiles.

From London, the two brothers migrated to Bombay in 1853. Bombay had developed into a major trading centre by that time; shipping was thriving, land had been reclaimed to expand the city, and links to the Deccan hinterland had been opened to facilitate trade. Perhaps the Watsons thought it made excellent business sense to relocate. I also have another pet theory about this migration to Bombay. Perhaps the Watson brothers attended the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, at the Crystal Palace? Perhaps they were enchanted with the Indian textiles they saw? Surely the Indian Pavillion was a vision to delight any silk mercer and draper!

Whatever the reason for migration - the two brothers arrived in Bombay in 1853, and set up shop here. They must have struck gold in Bombay - because they soon had three shops here, at Churchgate Street, Hamam Street and Meadow Street. Apparently it still wasn't enough. Within just ten years of arriving in Bombay, the Watson brothers made a grand bid for yet another building site. The original plans submitted for the building included a shop front on the ground floor, offices on the first and second floors, and residences (for themselves, I presume) on the third floor.

The plans the Watsons submitted conceived of a bold new design - a cast iron frame that was modelled on the Crystal Palace, where the London exhibion was held. Nothing like it had been seen in India before. By 1865, the initial plans for a shop changed; and the Watsons decided to build a grand new hotel instead. But the cast iron girders remained in the plan. Although there were problems with having the designs approved, the Watsons persevered, and pushed through with their plan.

The design involved the import of hundreds of cast iron girders. Arranged from top to bottom, these girders formed a sort of grand metal bird-cage. This sort of design actually exposed bare metal. It was in fact, the first multi-storey habitable building in the world in which all loads, including those of the brick walls, were carried on an iron frame. In that sense, it is the earliest pre-cursor to the modern-day skyscraper.

The crowning glory of the building design was a mansard - a type of roof that actually doubles up as a floor. The architects apparently wanted to cover the top with glass. It would have made a fantastic salon, eh? Or a really fancy penthouse suite for the who's who of Bombay's visitors.

The farmer had three sons, but two of them, John and William Watson, left Castle Carrock in the 1840's to start a drapery business in London, dealing in silks and other textiles.

From London, the two brothers migrated to Bombay in 1853. Bombay had developed into a major trading centre by that time; shipping was thriving, land had been reclaimed to expand the city, and links to the Deccan hinterland had been opened to facilitate trade. Perhaps the Watsons thought it made excellent business sense to relocate. I also have another pet theory about this migration to Bombay. Perhaps the Watson brothers attended the Great Exhibition of 1851 in London, at the Crystal Palace? Perhaps they were enchanted with the Indian textiles they saw? Surely the Indian Pavillion was a vision to delight any silk mercer and draper!

Whatever the reason for migration - the two brothers arrived in Bombay in 1853, and set up shop here. They must have struck gold in Bombay - because they soon had three shops here, at Churchgate Street, Hamam Street and Meadow Street. Apparently it still wasn't enough. Within just ten years of arriving in Bombay, the Watson brothers made a grand bid for yet another building site. The original plans submitted for the building included a shop front on the ground floor, offices on the first and second floors, and residences (for themselves, I presume) on the third floor.

The plans the Watsons submitted conceived of a bold new design - a cast iron frame that was modelled on the Crystal Palace, where the London exhibion was held. Nothing like it had been seen in India before. By 1865, the initial plans for a shop changed; and the Watsons decided to build a grand new hotel instead. But the cast iron girders remained in the plan. Although there were problems with having the designs approved, the Watsons persevered, and pushed through with their plan.

The design involved the import of hundreds of cast iron girders. Arranged from top to bottom, these girders formed a sort of grand metal bird-cage. This sort of design actually exposed bare metal. It was in fact, the first multi-storey habitable building in the world in which all loads, including those of the brick walls, were carried on an iron frame. In that sense, it is the earliest pre-cursor to the modern-day skyscraper.

The crowning glory of the building design was a mansard - a type of roof that actually doubles up as a floor. The architects apparently wanted to cover the top with glass. It would have made a fantastic salon, eh? Or a really fancy penthouse suite for the who's who of Bombay's visitors.

%2B-%2Bc1880's.JPG) |

| http://www.oldindianphotos.in/2012/11/watsons-hotel-bombay-mumbai-c1880s.html |

Of the two brothers, John and William Watson, we know this: William quit the drapery business to become a shipping agent. John Watson remained in the drapery and hotel business; but he returned to the village of Castle Carrock in 1869, just after Watsons Hotel was built. His sons, James Proctor and John Jr, inherited and ran the hotel successfully, until they too returned to Cumbria in 1896 (at the time of Bombay's bubonic plague).

With the owners gone, and with competition from new hotels such as Green's, Majestic, and the Taj, the birdcage hotel went into decline. In 2006, the World Monument Fund placed the hotel under the list of World Endangered Monuments.

Here's a recent photo I clicked; can you see the beautiful Minton floor tiling? The iron girders are still standing strong. The inside of the hotel has been divided up and sub-let to lots of small businesses. Next time you're in the area, pop into the building and take a quick look. And if you want a little challenge, then try to spot the Watsons logo on the outside of the building!===========================================

Among the many celebrated personalities that

Esplanade Mansion hosted, one of the guests was author Mark Twain who

had visited Bombay! Twain stayed at the former Watson's Hotel, and even

wrote a story in his book 'Following the Equator' on the Indian crows

that he saw from his room's balcony at the Hotel.

An extract from the book highlighting details of his room and the hotel

balcony in his story. .

PC in Public Domain

.

#saveesplanademansion #watsonshotel #esplanademansion #marktwain #followingtheequator #indiancrow #mumbaiheritage #mumbaiworldheritage #unescoworldheritage #unesco #kalaghoda #castironbuulding #oldbombay #bombayhistory #industrialheritage

A painting of the Watson's Hotel, at Castle

Carrock, UK. The original design included plans for a traditional

mansard roof, which was never built, as seen in image 2.

.

PC.1. www.castlecarrock.com

2.In public domain

.

.

#mumbaiworldheritage #unesco #esplanademansion #watsonshotel #fortmumbai #industrialheritage #ironcolumns