When Bombay overtook Calcutta: A history of India's financial geography

To

the current generation of scholars of finance and economics, this

question of when Bombay (now Mumbai) overtook Calcutta (Kolkata) would

sound absurd. A competition between Calcutta and Bombay over financial

domination? That was a thing?

Calcutta did not just compete but was once a much larger financial centre than Bombay. Older textbooks mention both Calcutta and Bombay as financial centres, with some preferring Calcutta over Bombay.

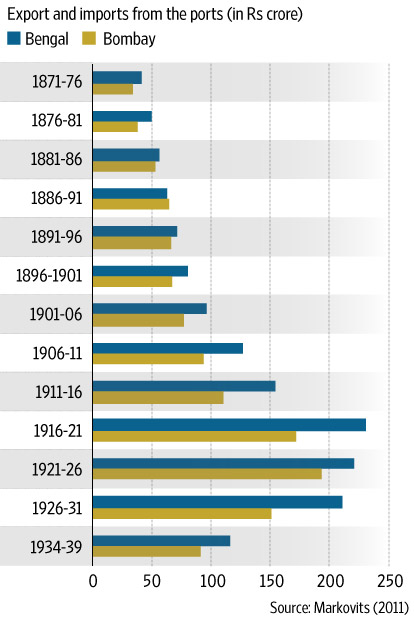

Charles Kindleberger, in his excellent 1974 essay The Formation of Financial Centers: A Study in Comparative Economic History, shows how major banks concentrate in political and commercial capitals leading to development of financial centres. Calcutta was not just the political but also the commercial capital of British. The trade volumes from Bengal were higher than Bombay for most part of the time period between 1871 and 1939.

Accordingly, when the East India Company decided to establish joint stock banking in their Indian colony, they started in Calcutta in 1806 followed by Bombay nearly 34 years later in 1840 (the one in Madras was found in 1843).

Just like trade data, the Bank of Bengal was also much larger than the Bank of Bombay for much of the history of the Presidency banks. This was mainly due to Bank of Bengal catering to a much larger population compared to Bank of Bombay. On top of this, more regions were accorded to Bank of Bengal compared to the two Presidency banks.

Given the large population, the Bank of Bengal captured larger deposits as well. One indicator of importance in this case is the volume of government deposits, which were much larger in Bengal given it was the political capital as well. The dominance continued till 1913 but Bombay was slowly closing the gap, as we saw in the trade data.

Moving on from banking, we also see larger number of companies being floated in Bengal compared to Bombay. Nearly 45-50% of Indian companies were floated in Bengal compared to Bombay’s share of 13-15%. By 1918, Calcutta and Bombay controlled 43% and 40% respectively of rupee companies and 73% and 19% for sterling companies. This again showing dominance of Calcutta over Bombay, especially in sterling markets mainly due to tea companies.

In per capita comparisons, though, Bombay was better placed than Calcutta. This indicates the relative prosperity of Bombay compared to Calcutta. For instance, the Bank of Bombay collected four times more deposits per person than Calcutta.

Even in terms of companies, we see Bombay having higher paid-up capital.

The next question, then, is when did Bombay eventually accelerate past Calcutta? One gets some cues from clearing house data. The clearing houses were established by Presidency banks and local banks to settle intra-bank payments. This continuous time-series gives more clarity on the evolving trends across clearing houses established in different parts of the country.

In 1913, total clearing house transactions were Rs65,035 lakh with Calcutta settling 51% of these transactions compared to Bombay’s share of 33.7%. Madras had a meagre share of 3.6%. Delhi was insignificant.

However, the gap between Calcutta and Bombay narrowed with each subsequent year. In 1947, the shares became almost equal. In fact, 1947 becomes the inflection point as from that point onwards, Bombay starts to gain over Calcutta. In 1950, Bombay’s share was nearly 6% higher than Calcutta. By 1965, Calcutta’s share had declined to 28% and Bombay was at 35%. The share of Madras is constant at 5-6% since 1947.

The share of Delhi (New Delhi later) becomes larger over time as well, mainly due to large banks such as the Punjab National Bank and Oriental Bank of Commerce that migrated from Pakistan and made their head office in Delhi.

It must be noted that from 1947 onwards, major gains are made in other clearing houses as well. This was due to efforts made to open clearing houses in other smaller centres. It was now no longer just a fight between Calcutta and Bombay. The payment and settlement system also evolved significantly over the years. Earlier, clearing houses were the only players in the game. Now they were one of the players.

Thus, it was around independence that Bombay eventually replaced Calcutta as the leading financial centre. Why did this happen?

Bimal C. Ghose points to several factors in 1943’s A Study of Indian Money Market:

• The world wars weakened the position of Calcutta significantly. In particular, World War II was severe on Calcutta’s economy with the virtual closure of the Calcutta port (RBI History, Volume I). This led to a decline in business in Calcutta affecting local money markets and banking.

• The fate of the Calcutta port made Bombay the colony’s numero uno port. Bombay was always much more naturally suited to being a port compared to Calcutta. After all, Bombay in Portuguese means “good bay”. The Calcutta port was 80 miles up the river from the sea, making it difficult for cargo ships. Bombay was nearer to the Suez Canal and received the bulk of imports from Europe. The shipping rates were also higher in Calcutta. Thus, with maritime trade concentrating in Bombay, the finance sector followed as well.

• Development of railways linked Bombay to not just the Deccan (which was the original purpose) but to Punjab as well. The port of Karachi was closer to Punjab, but Bombay was preferred, given the railway connectivity.

• Indigenous bankers in Bombay offered exceptional facilities and translated their practices into formal banking.

• Bombay was also home to three important markets: stock exchange, cotton and bullion. Calcutta just had jute, which was mainly exported. There was the Calcutta Stock Exchange but the one in Bombay was much older and more significant, perhaps due to its proximity to western financial centres.

Claude Markovits, in his 2011 Premier Industrial Centres Bombay and Calcutta, further adds that the response of entrepreneurs in the two regions to shocks was very different. The ones in Bombay responded to shocks by pivoting to different business opportunities. The same was not the case with Calcutta-based entrepreneurs.

India also saw a large number of banking failures during the period 1915-65, with nearly 1,500 banks closing in the country (based on the writer’s analysis, drawn from various issues of statistical tables related to banks in India). Out of these, 126 banks closed in Bombay whereas nearly 360 banks closed in Bengal. The closure was severe in Bengal from 1947 onwards (after becoming West Bengal), with 168 closing in the period 1947-65 whereas just 13 closed in the Bombay region in the same period.

The large-scale failures in Bengal were partly due to Partition and partly due to poor management of these banks. This wide gap in failures of banks undoubtedly helped strengthen the case of Bombay as the financial centre.

Another factor is the choice of location of India’s central bank. The location of the central bank is an important factor, as suggested by Kindleberger. John Maynard Keynes and Sir E. Cable made a memo on establishing a central bank in India in 1914. The two cities put forth as potential sites to headquarter the bank were Calcutta and, believe it or not, Delhi. Bombay was not even considered. Delhi was preferred then as it was considered independent of the three Presidency bank offices!

However, by the time of the RBI’s formation in 1935, the contest was between Calcutta and Bombay. The former represented the past and the latter was the future. Thus it was decided to make both cities joint headquarters for India’s central bank. Indeed, the first board meeting was held In Calcutta:

Calcutta and Bombay being the most important commercial and financial centres in the country, it became the practice of the Governors to divide their time approximately equally between these two places (apart from brief visits to other centres) in conformity with the spirit of these recommendations. The Bank also acquired residential accommodation for the Governor in the two cities.

However, the then-governor James Taylor made a request to shift the head office to Bombay in 1937:

The experience of the last two years has shown that the present practice of migrating from one centre to another throws an impossible burden on the administration of the bank and involves great waste of time and duplication of work.

His request was acceded and in December 1937, the central office was permanently transferred to Bombay. However, the governor continued to shuttle between Calcutta and Bombay. In 1949, on then-governor B. Rama Rau’s request, Calcutta House was sold off, making Bombay the sole location of the Indian central bank.

This decision was obviously due to Bombay emerging as a major financial centre. But the shift of the central bank further reinforced the trend and led to more financial activity shifting to Bombay. This is also reflected in the clearing house trends and banking failures shown above.

Overall, this history of financial geography is quite illuminating as it tells you a lot about how several forces shape (and break) financial centres. In India’s case, this is even more so, given the interplay and politics between colonial and domestic interests. The author will be happy to engage with interested readers on this subject.

Sources

Bimal C. Ghose (1943), A Study of Indian Money Market, Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta

Charles P. Kindleberger (1974), "The Formation of Financial Centers: A Study in Comparative Economic History", Princeton Studies in International Finance No.36

Claude Markovits (2011), "Premier Industrial Centres Bombay and Calcutta" in The Oxford Anthology of Indian Business, edited by Medha Kudaisya, Oxford University Press, Delhi

RBI (1970), History of Reserve Bank of India (1935-51) Vol. 1, Times of India Press, Bombay

Amol Agrawal is a PhD student at IIM Bangalore working on Indian banking history. He writes a blog called Mostly Economics.

Comments are welcome at feedback@livemint.com

Calcutta did not just compete but was once a much larger financial centre than Bombay. Older textbooks mention both Calcutta and Bombay as financial centres, with some preferring Calcutta over Bombay.

Charles Kindleberger, in his excellent 1974 essay The Formation of Financial Centers: A Study in Comparative Economic History, shows how major banks concentrate in political and commercial capitals leading to development of financial centres. Calcutta was not just the political but also the commercial capital of British. The trade volumes from Bengal were higher than Bombay for most part of the time period between 1871 and 1939.

Accordingly, when the East India Company decided to establish joint stock banking in their Indian colony, they started in Calcutta in 1806 followed by Bombay nearly 34 years later in 1840 (the one in Madras was found in 1843).

Just like trade data, the Bank of Bengal was also much larger than the Bank of Bombay for much of the history of the Presidency banks. This was mainly due to Bank of Bengal catering to a much larger population compared to Bank of Bombay. On top of this, more regions were accorded to Bank of Bengal compared to the two Presidency banks.

Given the large population, the Bank of Bengal captured larger deposits as well. One indicator of importance in this case is the volume of government deposits, which were much larger in Bengal given it was the political capital as well. The dominance continued till 1913 but Bombay was slowly closing the gap, as we saw in the trade data.

Moving on from banking, we also see larger number of companies being floated in Bengal compared to Bombay. Nearly 45-50% of Indian companies were floated in Bengal compared to Bombay’s share of 13-15%. By 1918, Calcutta and Bombay controlled 43% and 40% respectively of rupee companies and 73% and 19% for sterling companies. This again showing dominance of Calcutta over Bombay, especially in sterling markets mainly due to tea companies.

In per capita comparisons, though, Bombay was better placed than Calcutta. This indicates the relative prosperity of Bombay compared to Calcutta. For instance, the Bank of Bombay collected four times more deposits per person than Calcutta.

Even in terms of companies, we see Bombay having higher paid-up capital.

The next question, then, is when did Bombay eventually accelerate past Calcutta? One gets some cues from clearing house data. The clearing houses were established by Presidency banks and local banks to settle intra-bank payments. This continuous time-series gives more clarity on the evolving trends across clearing houses established in different parts of the country.

In 1913, total clearing house transactions were Rs65,035 lakh with Calcutta settling 51% of these transactions compared to Bombay’s share of 33.7%. Madras had a meagre share of 3.6%. Delhi was insignificant.

However, the gap between Calcutta and Bombay narrowed with each subsequent year. In 1947, the shares became almost equal. In fact, 1947 becomes the inflection point as from that point onwards, Bombay starts to gain over Calcutta. In 1950, Bombay’s share was nearly 6% higher than Calcutta. By 1965, Calcutta’s share had declined to 28% and Bombay was at 35%. The share of Madras is constant at 5-6% since 1947.

The share of Delhi (New Delhi later) becomes larger over time as well, mainly due to large banks such as the Punjab National Bank and Oriental Bank of Commerce that migrated from Pakistan and made their head office in Delhi.

It must be noted that from 1947 onwards, major gains are made in other clearing houses as well. This was due to efforts made to open clearing houses in other smaller centres. It was now no longer just a fight between Calcutta and Bombay. The payment and settlement system also evolved significantly over the years. Earlier, clearing houses were the only players in the game. Now they were one of the players.

Thus, it was around independence that Bombay eventually replaced Calcutta as the leading financial centre. Why did this happen?

Bimal C. Ghose points to several factors in 1943’s A Study of Indian Money Market:

• The world wars weakened the position of Calcutta significantly. In particular, World War II was severe on Calcutta’s economy with the virtual closure of the Calcutta port (RBI History, Volume I). This led to a decline in business in Calcutta affecting local money markets and banking.

• The fate of the Calcutta port made Bombay the colony’s numero uno port. Bombay was always much more naturally suited to being a port compared to Calcutta. After all, Bombay in Portuguese means “good bay”. The Calcutta port was 80 miles up the river from the sea, making it difficult for cargo ships. Bombay was nearer to the Suez Canal and received the bulk of imports from Europe. The shipping rates were also higher in Calcutta. Thus, with maritime trade concentrating in Bombay, the finance sector followed as well.

• Development of railways linked Bombay to not just the Deccan (which was the original purpose) but to Punjab as well. The port of Karachi was closer to Punjab, but Bombay was preferred, given the railway connectivity.

• Indigenous bankers in Bombay offered exceptional facilities and translated their practices into formal banking.

• Bombay was also home to three important markets: stock exchange, cotton and bullion. Calcutta just had jute, which was mainly exported. There was the Calcutta Stock Exchange but the one in Bombay was much older and more significant, perhaps due to its proximity to western financial centres.

Claude Markovits, in his 2011 Premier Industrial Centres Bombay and Calcutta, further adds that the response of entrepreneurs in the two regions to shocks was very different. The ones in Bombay responded to shocks by pivoting to different business opportunities. The same was not the case with Calcutta-based entrepreneurs.

India also saw a large number of banking failures during the period 1915-65, with nearly 1,500 banks closing in the country (based on the writer’s analysis, drawn from various issues of statistical tables related to banks in India). Out of these, 126 banks closed in Bombay whereas nearly 360 banks closed in Bengal. The closure was severe in Bengal from 1947 onwards (after becoming West Bengal), with 168 closing in the period 1947-65 whereas just 13 closed in the Bombay region in the same period.

The large-scale failures in Bengal were partly due to Partition and partly due to poor management of these banks. This wide gap in failures of banks undoubtedly helped strengthen the case of Bombay as the financial centre.

Another factor is the choice of location of India’s central bank. The location of the central bank is an important factor, as suggested by Kindleberger. John Maynard Keynes and Sir E. Cable made a memo on establishing a central bank in India in 1914. The two cities put forth as potential sites to headquarter the bank were Calcutta and, believe it or not, Delhi. Bombay was not even considered. Delhi was preferred then as it was considered independent of the three Presidency bank offices!

However, by the time of the RBI’s formation in 1935, the contest was between Calcutta and Bombay. The former represented the past and the latter was the future. Thus it was decided to make both cities joint headquarters for India’s central bank. Indeed, the first board meeting was held In Calcutta:

Calcutta and Bombay being the most important commercial and financial centres in the country, it became the practice of the Governors to divide their time approximately equally between these two places (apart from brief visits to other centres) in conformity with the spirit of these recommendations. The Bank also acquired residential accommodation for the Governor in the two cities.

However, the then-governor James Taylor made a request to shift the head office to Bombay in 1937:

The experience of the last two years has shown that the present practice of migrating from one centre to another throws an impossible burden on the administration of the bank and involves great waste of time and duplication of work.

His request was acceded and in December 1937, the central office was permanently transferred to Bombay. However, the governor continued to shuttle between Calcutta and Bombay. In 1949, on then-governor B. Rama Rau’s request, Calcutta House was sold off, making Bombay the sole location of the Indian central bank.

This decision was obviously due to Bombay emerging as a major financial centre. But the shift of the central bank further reinforced the trend and led to more financial activity shifting to Bombay. This is also reflected in the clearing house trends and banking failures shown above.

Overall, this history of financial geography is quite illuminating as it tells you a lot about how several forces shape (and break) financial centres. In India’s case, this is even more so, given the interplay and politics between colonial and domestic interests. The author will be happy to engage with interested readers on this subject.

Sources

Bimal C. Ghose (1943), A Study of Indian Money Market, Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta

Charles P. Kindleberger (1974), "The Formation of Financial Centers: A Study in Comparative Economic History", Princeton Studies in International Finance No.36

Claude Markovits (2011), "Premier Industrial Centres Bombay and Calcutta" in The Oxford Anthology of Indian Business, edited by Medha Kudaisya, Oxford University Press, Delhi

RBI (1970), History of Reserve Bank of India (1935-51) Vol. 1, Times of India Press, Bombay

Amol Agrawal is a PhD student at IIM Bangalore working on Indian banking history. He writes a blog called Mostly Economics.

Comments are welcome at feedback@livemint.com