The wounds have never healed’: living through the terror of partition

The creation of India and Pakistan in 1947 led to horrific sectarian

violence and made millions refugees overnight. Seventy years on, five

survivors remember

stories of partition

stories of partition

My father, who was then at Aitchison college, an elite boarding school, remembers being summoned by the English headmaster to an extraordinary assembly in April 1947. School usually broke up for summer holidays in the first week of June, but the headmaster announced that, this year, term would end sooner – in fact, the school would close the following day. “Partition was expected in 1948, but the date had been brought forward and riots had already erupted in parts of the North-West Frontier province and some areas of Punjab,” recalls my father. “Since he could not guarantee our safety, our headmaster had decided to send us home.” My father took what he thought was temporary leave of his many Hindu and Sikh friends and left for Shergarh, his village in Okara district, 70 miles south-west of Lahore.

Luckily, the line that was drawn two months later, severing Punjab in two, allotted Shergarh to Pakistan. My Muslim father had the great fortune of not having to flee his ancestral home. Nonetheless, three months of pure terror followed. “I have never known a period of greater fear and uncertainty,” he says. Shergarh was surrounded by Sikh villages. Once killings began, the villagers braced themselves for an attack every day. “Wild bands of marauding men armed with sickles, axes and swords roamed the open countryside, killing and mutilating anyone they found of the opposite faith.”

Yet my father’s grandfather had been on good terms with his Sikh and Hindu neighbours. This closeness was not unusual in pre-partition Punjab. “There was no intermarriage between the communities and we tended not to eat at each other’s houses, but we were fast friends,” recalls my mother’s brother, Syed Babar Ali, now 91.

When my father returned to school in September, he was one of only 30 of the 300 boys who had left in April. The rest, Hindus and Sikhs, had gone. The school had also lost many of its staff. “There were more cows in the school dairy than boys in the classroom,” he remembers. “Aitchison was a haunted place.”

True, political tension had been rising inexorably in the two decades preceding partition, as leaders of the Indian National Congress and the Muslim League bickered over the terms of the bitter divorce. But the suddenness, scale and ferocity of the violence that erupted in 1947 was still shocking. As historians and writers such as Nisid Hajary and Saadat Hassan Manto have noted, it was a time when the normal mores of civilisation were suspended and neighbours massacred each other without a thought.

The figures speak for themselves, but it was the barbarity that was unleashed that was terrifying. Trains filled with refugees crossing the border were stopped and every man, woman and child on board slaughtered. Only the engine driver was spared, so he could take his grisly cargo to its destination. Women – some as young as 10 – were captured and raped, and pregnant women’s bellies were slit open. Babies were swung against walls and their heads smashed in. My great aunt, then a married woman living in the walled city of Lahore, told me she had seen a man crossing an eerily quiet street littered with corpses. He was halfway across when someone shot at him. Scooping up the body of a toddler, he used it as a protective shield as he raced across. “I don’t know if that man was Muslim or Hindu,” she told me 30 years later. “It was dreadful either way.”

Partition, as Pakistani historian Ayesha Jalal has observed, was “the central historical event in 20th-century south Asia”. It scarred those who lived through it and permanently soured relations between the two countries. “It is impossible to understand relations between India and Pakistan without looking back to partition,” says Alex von Tunzelmann, a historian and the author of Indian Summer, a history of partition. “The wounds have never healed.”

Here, five people share their stories of living through partition.

Mazhar Malik, 86

By May, riots had begun in some districts of Punjab. There was also growing unease in Jammu, but, accustomed as we were to such disruptions, we thought it was more of the same. Srinagar was peaceful, so we moved in with an aunt and uncle who lived there, planning to return home as soon as things calmed down.

At partition, there was doubt as to which country the state of Jammu would join. It had a Muslim majority, but its ruler, Hari Singh, was a Hindu. By mid-August, the rest of India had already been partitioned, but our fates still hung in the balance. As the month wore on, Hindu and Sikh refugees limped into Srinagar, narrating stories of the bloodshed they had escaped in the Punjab. It was not long before riots broke out all over Jammu.

In September, my parents, along with two other Muslim families, decided to move temporarily to Pakistan for safety. A truck set off from Rawalpindi to collect us. On the eve of our departure, my father decided he would stay on. As a civil servant, he felt duty-bound to return to Jammu, since he did not have official permission to leave his post. He assured my mother he would apply for leave and join us immediately.

On 28 September, we boarded the truck with two suitcases and two rolls of bedding each and left for Muzaffarabad, Pakistan, along the Jhelum River road – a beautiful drive in any other circumstances. My father reported for duty in Jammu city on 5 October. In Pakistan, my mother managed to make contact with my father’s younger brother, an accountant who was stationed at Rasul headworks in northern Punjab, and we went on to him.

Facebook

TwitterPinterestMuslim refugees at a camp outside Delhi in September 1947. Photograph: Bettmann ArchiveOn 8 November, we received a relative from Gujranwala, a town in

Punjab some distance from Rasul. He told us that, three days before, our

father had left Jammu in a convoy of trucks arranged by the state

government and escorted by its troops. There were about 1,200 Muslims in

the trucks. Dusk was falling when the convoy stopped suddenly beyond

the city limits and the troops ordered everyone to disembark. In the

gathering darkness, the travellers saw clusters of men emerge from

behind trees and form two concentric circles around them. They were

armed with staffs, swords and daggers. At a signal from their leader,

they rushed at the unarmed civilians, hacking, slashing, smashing. It

was, he told us, a scene of unimaginable violence. People ran hither and

thither, begging for mercy; mothers tried to shield their children; old

people fell silently to their knees; men tried in vain to fight back.

Mercifully, because it was dark by then, about one-third succeeded in

escaping. The border was just a few miles away and the lucky ones

managed to straggle across. Our father was not one of them. “Malik Sahib

was martyred that evening,” said our relative, lowering his eyes.In fact, the news was incorrect: my father had volunteered to leave

in the convoy, but he was asked by the authorities to stay back and join

one departing the next day.is time, it was broad daylight and the killers were more organised.

They cut down everyone and threw the bodies into a nearby canal. A

handful survived – those they had left for dead or who had jumped into

the canal. A friend of my father’s, Chaudhry Hameedullah, was among the

survivors. He said: “I saw Sahib being cut down. But I can’t say whether

he survived or not.”Because of this tiny element of doubt, my mother clung on to hope for months.I returned to Jammu in 1979, accompanied by my wife and my daughter.

We still have relatives there. I saw my old house, met my Hindu school

friends, visited my school. But I went with only one purpose: to see the

place where they killed my father.Sohinder Nath Chopra, 82I was born in a small village called Chahal Kalan in the district of

Gujranwala, Punjab. I still dream about it. Chahal Kalan was surrounded

by open fields and lakes to which migratory birds came. You could hear

the tinkling bells of the bullocks driving Persian wells. We used dung

cakes for fuel. During winter, the smoke from our fires and the mist

from the lakes would mingle and enshroud our village.In my village, we Hindus made up only 5% of the population. The rest

were Muslims. But there was absolute harmony. Partition was announced on

15 August. Hindus and Muslims decided jointly that we would guard our

village together. Night watch groups were formed. A week later, rumours

spread that the village was going to be invaded. So, my parents and

other Hindus sent their children to a neighboring Sikh village for

safety. At lunchtime, we heard our village had been overrun and a Muslim

mob was coming to kill us; we ran away in panic. But by the evening we

heard our village hadn’t been invaded at all. It had been a hoax.

Facebook

TwitterPinterestMuslim refugees at a camp outside Delhi in September 1947. Photograph: Bettmann ArchiveOn 8 November, we received a relative from Gujranwala, a town in

Punjab some distance from Rasul. He told us that, three days before, our

father had left Jammu in a convoy of trucks arranged by the state

government and escorted by its troops. There were about 1,200 Muslims in

the trucks. Dusk was falling when the convoy stopped suddenly beyond

the city limits and the troops ordered everyone to disembark. In the

gathering darkness, the travellers saw clusters of men emerge from

behind trees and form two concentric circles around them. They were

armed with staffs, swords and daggers. At a signal from their leader,

they rushed at the unarmed civilians, hacking, slashing, smashing. It

was, he told us, a scene of unimaginable violence. People ran hither and

thither, begging for mercy; mothers tried to shield their children; old

people fell silently to their knees; men tried in vain to fight back.

Mercifully, because it was dark by then, about one-third succeeded in

escaping. The border was just a few miles away and the lucky ones

managed to straggle across. Our father was not one of them. “Malik Sahib

was martyred that evening,” said our relative, lowering his eyes.In fact, the news was incorrect: my father had volunteered to leave

in the convoy, but he was asked by the authorities to stay back and join

one departing the next day.is time, it was broad daylight and the killers were more organised.

They cut down everyone and threw the bodies into a nearby canal. A

handful survived – those they had left for dead or who had jumped into

the canal. A friend of my father’s, Chaudhry Hameedullah, was among the

survivors. He said: “I saw Sahib being cut down. But I can’t say whether

he survived or not.”Because of this tiny element of doubt, my mother clung on to hope for months.I returned to Jammu in 1979, accompanied by my wife and my daughter.

We still have relatives there. I saw my old house, met my Hindu school

friends, visited my school. But I went with only one purpose: to see the

place where they killed my father.Sohinder Nath Chopra, 82I was born in a small village called Chahal Kalan in the district of

Gujranwala, Punjab. I still dream about it. Chahal Kalan was surrounded

by open fields and lakes to which migratory birds came. You could hear

the tinkling bells of the bullocks driving Persian wells. We used dung

cakes for fuel. During winter, the smoke from our fires and the mist

from the lakes would mingle and enshroud our village.In my village, we Hindus made up only 5% of the population. The rest

were Muslims. But there was absolute harmony. Partition was announced on

15 August. Hindus and Muslims decided jointly that we would guard our

village together. Night watch groups were formed. A week later, rumours

spread that the village was going to be invaded. So, my parents and

other Hindus sent their children to a neighboring Sikh village for

safety. At lunchtime, we heard our village had been overrun and a Muslim

mob was coming to kill us; we ran away in panic. But by the evening we

heard our village hadn’t been invaded at all. It had been a hoax. Facebook

TwitterPinterestHindu refugees from eastern Bengal, which became part of

Pakistan after partition, arrive in Bangaon, western Bengal, circa 1947.

The town then marked the border with India. Photograph:

Gamma-Keystone/Getty ImagesA few days later, a military chief arrived in a jeep to help us

evacuate. But it was a small jeep and ours was a large family, so my

father declined the offer. He said: “We trust our neighbours and if we

have to become Muslims we will become Muslims, but we will not leave.”

The mullah of the neighbouring mosque sent a message to my father; if he

wanted to convert, he would be happy to perform the ceremony. A couple

of days later, however, the mullah received a message from the Pakistan

administration not to convert anybody or encourage them to stay. So, he

advised my father to leave as soon as possible. We were all set to go

when our neighbours and some people from outside our village stormed our

home. But our Christian servants protected us and managed to whisk us

out unharmed. We had only two pieces of baggage. One was a shiny trunk,

actually a decoy, containing a few clothes. In a small bag, we carried

all our valuables – gold, cash and whatever we could stuff in it.It had rained the night before and the road was wet. My mother was

nearing 50. She had never walked out of the house; now she was running

on bare feet. There were about 1,000 people in that caravan, guarded by

the army on three sides. People were standing on their rooftops,

watching us pass. My brother’s Muslim friends ran up to embrace him and

say goodbye. My friends were also waving to me from a distance. We spent

the night in a primary school. There was no light, no bathroom.Early the next morning, army trucks took us to the next camp in

Gujranwala city, where there was complete chaos. We heard there that my

mother’s ancestral village had been attacked and many people had been

killed. My mother, naturally, was very upset. My brother had also been

there then. But, pretending to be a Muslim, he had escaped

Facebook

TwitterPinterestHindu refugees from eastern Bengal, which became part of

Pakistan after partition, arrive in Bangaon, western Bengal, circa 1947.

The town then marked the border with India. Photograph:

Gamma-Keystone/Getty ImagesA few days later, a military chief arrived in a jeep to help us

evacuate. But it was a small jeep and ours was a large family, so my

father declined the offer. He said: “We trust our neighbours and if we

have to become Muslims we will become Muslims, but we will not leave.”

The mullah of the neighbouring mosque sent a message to my father; if he

wanted to convert, he would be happy to perform the ceremony. A couple

of days later, however, the mullah received a message from the Pakistan

administration not to convert anybody or encourage them to stay. So, he

advised my father to leave as soon as possible. We were all set to go

when our neighbours and some people from outside our village stormed our

home. But our Christian servants protected us and managed to whisk us

out unharmed. We had only two pieces of baggage. One was a shiny trunk,

actually a decoy, containing a few clothes. In a small bag, we carried

all our valuables – gold, cash and whatever we could stuff in it.It had rained the night before and the road was wet. My mother was

nearing 50. She had never walked out of the house; now she was running

on bare feet. There were about 1,000 people in that caravan, guarded by

the army on three sides. People were standing on their rooftops,

watching us pass. My brother’s Muslim friends ran up to embrace him and

say goodbye. My friends were also waving to me from a distance. We spent

the night in a primary school. There was no light, no bathroom.Early the next morning, army trucks took us to the next camp in

Gujranwala city, where there was complete chaos. We heard there that my

mother’s ancestral village had been attacked and many people had been

killed. My mother, naturally, was very upset. My brother had also been

there then. But, pretending to be a Muslim, he had escapedBreak the silence on partition and British colonial history – before it’s too lateKavita PuriWhen our caravan finally crossed the border, there were shouts of: “Hindustan zindabad! Bharatmata zindabad!” (“Long live Mother India!”) People were sobbing. Food and water were being handed around. It was a great relief to be safe, finally. Since we had relatives in Delhi, we decided to go there.We were able to find space on a train, but it was crammed full of wounded passengers and wailing children. I was excited, because it was my first time on a train, but the stench of blood was overpowering. Our carriage was disconnected at Samalkha in Haryana, where, for the first time, I saw pigs, peacocks and monkeys. The people of Samalkha arranged food. They sent a doctor to tend the wounded. They called us Pakistanis, but they were very helpful.Coming from a village, I was wonderstruck by Delhi. My cousin wanted to show me around, so he took me on a bicycle to see the sights, which were all deserted.Almost overnight, Delhi’s population swelled from half a million to one and a half million. Necessities were in short supply. You needed a ration card for everything. There were long queues for supplies and fights broke out frequently. People thought British rule was much better. Government machinery had been expanded enormously to cope with the demands, and new recruits were refugees. This brought a lot of corruption, since everybody wanted to make money. That was the atmosphere at that time.

Muneera Salahuddin, 86I was a teenager and living in Lahore, near the railway station. Though we Muslims were in the majority, ours was a mixed area, with Hindus, Muslims and Sikhs living in close proximity. To my knowledge, there hadn’t been any trouble before. Yes, we didn’t eat at each other’s houses, but otherwise we lived on amicable terms. Opposite our house were a number of shops owned by Hindus. As partition neared, most of them left for Delhi. But a grocer, having sent his family on for safety, had stayed back to wrap up his business. Our Muslim servants frequented his shop and were friends with him. When the killings started, they smuggled him into our home for safety. And there he stayed, while the city burned and the streets piled up with dead bodies.One day, I was standing on the veranda fronting our bungalow. Since the house was on a plinth, I had a good view of the street outside and saw the shopkeeper creep out of the gate. I think, because he was a strict Hindu, he had a problem sharing a toilet with our Muslim staff and was going out to relieve himself. Before I could call out, a mob descended on him. One minute he was carefully closing the gate and the next he had been torn to shreds. I must have screamed, because my elder brother charged out, clamped a hand over my eyes and dragged me back into the house.. But it was too late. I had already seen everything: when they slit his throat, a fountain of blood shot up, and they ripped open his stomach so that his intestines spilled out. It has been 70 years, but I can’t forget that sight.

Jaya Thadani, 90

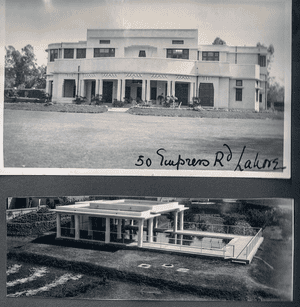

‘It was the attack on the plural, liberal values he lived by that broke my father’s heart’ ... Jaya Thadani.We had a beautiful house on Empress Road in Lahore. Built in 1933, it

was the first “modern” art deco house in the city. There was a sweeping

marble staircase, a fine library, parquet flooring and a garden spread

over three acres. There was also a swimming pool and an orchard of fruit

trees. In addition to my father’s library, the house was full of

treasures my mother had collected – Sèvres china, Venetian glass,

antique silver. My father, Kanwar Dalip Singh (a grandson of the

Maharaja of Kapurthala), was a high court judge. My mother, Reva, was a

bon vivant and a famous hostess. There would be formal dinners at our

table that could seat 18, plus dancing and live bands and music recitals

and amateur dramatics. Although our ancestors were Sikhs, my father was

Christian and my mother was a follower of Brahmo Samaj, a reformist Hindu movement. They had many Muslim friends, who were constantly in and out of our house.I was born in Lahore and educated there. In July 1947, I left for

England. I was there when partition happened. My parents were in Lahore.

Sensing the way the wind was blowing, my father had already decided to

sell the house to the US consulate. My father’s closest friends were two

Muslim gentlemen, Feroz Khan Noon (later Pakistan’s prime minister) and Khizar Hayat Tiwana

(premier of the Punjab until 1947) and they pleaded with my father not

to leave. He was a Christian, he would be safe. But my father was

adamant. He said, presciently, that there would be no place for

minorities in Pakistan or India.

‘It was the attack on the plural, liberal values he lived by that broke my father’s heart’ ... Jaya Thadani.We had a beautiful house on Empress Road in Lahore. Built in 1933, it

was the first “modern” art deco house in the city. There was a sweeping

marble staircase, a fine library, parquet flooring and a garden spread

over three acres. There was also a swimming pool and an orchard of fruit

trees. In addition to my father’s library, the house was full of

treasures my mother had collected – Sèvres china, Venetian glass,

antique silver. My father, Kanwar Dalip Singh (a grandson of the

Maharaja of Kapurthala), was a high court judge. My mother, Reva, was a

bon vivant and a famous hostess. There would be formal dinners at our

table that could seat 18, plus dancing and live bands and music recitals

and amateur dramatics. Although our ancestors were Sikhs, my father was

Christian and my mother was a follower of Brahmo Samaj, a reformist Hindu movement. They had many Muslim friends, who were constantly in and out of our house.I was born in Lahore and educated there. In July 1947, I left for

England. I was there when partition happened. My parents were in Lahore.

Sensing the way the wind was blowing, my father had already decided to

sell the house to the US consulate. My father’s closest friends were two

Muslim gentlemen, Feroz Khan Noon (later Pakistan’s prime minister) and Khizar Hayat Tiwana

(premier of the Punjab until 1947) and they pleaded with my father not

to leave. He was a Christian, he would be safe. But my father was

adamant. He said, presciently, that there would be no place for

minorities in Pakistan or India. Facebook

TwitterPinterest‘My parents had many Muslim friends, who were constantly

in and out of our house’ ... the Thadanis’ home on Empress Road in

Lahore.

As we had family in Delhi, he thought we would go there. When the

murders and the plundering began, Feroz and Khizar provided Muslim

sentries to protect us. But all around was mayhem. My parents lingered

until the beginning of August, when another dear Muslim friend, Ishat

Habibullah, told my parents: “Go now, while you can. Don’t worry about

your things. I’ll look after them.” My parents packed two suitcases and

left. I think it was the hardest thing they ever did. My father never

recovered. It wasn’t the house – Maharajah Harnam Singh, my grandfather,

had walked away from the state of Kapurthala when he converted to

Christianity, so what was a mere house? It was the attack on that

community of friendship, the plural, liberal values he lived by, that

broke his heart.hi was like going to another planet. My parents couldn’t read the

street signs, which were in Hindi, not Urdu. They had lost their

community. Then came a surprise. A few months later, they received a

letter from Ishat telling them he was sending their things. Trucks duly

arrived from Lahore, filled with everything they had left – down to the

notepaper in my mother’s desk, stamped with our Empress Road address –

except for my mother’s Sèvres dinner service, my father’s edition of

Shakespeare’s folio that he had received as a wedding present (I later

discovered both had been purloined by the Americans) and our dining

table, which was too big to put into the truck.I was born in that house on Empress Road. I had thought I would die

there. Like my father, I never recovered. The one thing that displaced

people know is that they will never go home. Save for a brief period of

my life when I lived in London and managed to find some likeminded

people, I have never felt at home again.

Facebook

TwitterPinterest‘My parents had many Muslim friends, who were constantly

in and out of our house’ ... the Thadanis’ home on Empress Road in

Lahore.

As we had family in Delhi, he thought we would go there. When the

murders and the plundering began, Feroz and Khizar provided Muslim

sentries to protect us. But all around was mayhem. My parents lingered

until the beginning of August, when another dear Muslim friend, Ishat

Habibullah, told my parents: “Go now, while you can. Don’t worry about

your things. I’ll look after them.” My parents packed two suitcases and

left. I think it was the hardest thing they ever did. My father never

recovered. It wasn’t the house – Maharajah Harnam Singh, my grandfather,

had walked away from the state of Kapurthala when he converted to

Christianity, so what was a mere house? It was the attack on that

community of friendship, the plural, liberal values he lived by, that

broke his heart.hi was like going to another planet. My parents couldn’t read the

street signs, which were in Hindi, not Urdu. They had lost their

community. Then came a surprise. A few months later, they received a

letter from Ishat telling them he was sending their things. Trucks duly

arrived from Lahore, filled with everything they had left – down to the

notepaper in my mother’s desk, stamped with our Empress Road address –

except for my mother’s Sèvres dinner service, my father’s edition of

Shakespeare’s folio that he had received as a wedding present (I later

discovered both had been purloined by the Americans) and our dining

table, which was too big to put into the truck.I was born in that house on Empress Road. I had thought I would die

there. Like my father, I never recovered. The one thing that displaced

people know is that they will never go home. Save for a brief period of

my life when I lived in London and managed to find some likeminded

people, I have never felt at home again. Anjolie Ela Menon, 77

Facebook

TwitterPinterest ‘Very little art came out of those experiences. I think

we don’t want to remember’ ... Anjolie Ela Menon in 2002. Photograph:

India Today Group/Getty Images

“I was seven years old at partition. My father was a lieutenant

colonel in command of a hospital in a lovely hill station called Murree,

in what became Pakistan. Independence had taken place a week earlier,

but everything seemed calm and quiet. We were in no hurry to leave; we

hadn’t packed anything. On 24 August, my father went to see a good

friend of his, a Hindu, who was a civilian doctor. There were rumours in

the market that there was going to be trouble and we Hindus were

advised to leave. But my father’s friend was adamant he wasn’t leaving.

Born in Murree, he had practised there for 40 years. The next morning,

he was discovered in his house, lying dead in a pool of blood. My father

decided to get the family out immediately. We left our house as it was.

Facebook

TwitterPinterest ‘Very little art came out of those experiences. I think

we don’t want to remember’ ... Anjolie Ela Menon in 2002. Photograph:

India Today Group/Getty Images

“I was seven years old at partition. My father was a lieutenant

colonel in command of a hospital in a lovely hill station called Murree,

in what became Pakistan. Independence had taken place a week earlier,

but everything seemed calm and quiet. We were in no hurry to leave; we

hadn’t packed anything. On 24 August, my father went to see a good

friend of his, a Hindu, who was a civilian doctor. There were rumours in

the market that there was going to be trouble and we Hindus were

advised to leave. But my father’s friend was adamant he wasn’t leaving.

Born in Murree, he had practised there for 40 years. The next morning,

he was discovered in his house, lying dead in a pool of blood. My father

decided to get the family out immediately. We left our house as it was.I remember being made to lie on the floor of the truck because all along the 30-mile journey to army headquarters at Rawalpindi our vehicle was being fired on by snipers. Finally, we reached the army mess, where there was a military Dakota plane leaving for Delhi. My father managed to get my mother, myself, my younger sister and one of our servants on that flight. We sat on the floor alongside lots of soldiers, the family of a Sikh doctor and a number of sacks.

The day we arrived at my aunt’s in Delhi, her Muslim dhobi [washerman] staggered into the house clutching his abdomen. His stomach had been slashed and he was holding his intestines.

By September, trains were arriving from Pakistan full of dead bodies. My father and his Hindu colleague, Dr Basu, had joined a convoy of trucks from Rawalpindi to Delhi. They left around 29 August and we didn’t know whether they were dead or alive until the end of September, when my exhausted father arrived and told us about thousands of refugees and the River Jhelum, which had run red with blood. Dr Basu and my father, who was a surgeon, had operated on wounded people left by the road. They ran out of anaesthetic and catgut so they made do with ordinary thread. Luckily, they had a big canteen containing liquor, so they made patients drink it as anaesthetic and poured it on to wounds to stop infection.

I grew up and became a painter. It strikes me as strange that very little art came out of those experiences. I think we don’t want to remember.

Accounts of Sohinder Nath Chopra and Anjolie Ela Menon courtesy of the Partition Museum, Amritsar

‘Very little art came out of those experiences. I think we don’t want to remember’ ... Anjolie Ela Menon in 2002. Photograph: India Today Group/Getty Images “I was seven years old at partition. My father was a lieutenant colonel in command of a hospital in a lovely hill station called Murree, in what became Pakistan. Independence had taken place a week earlier, but everything seemed calm and quiet. We were in no hurry to leave; we hadn’t packed anything. On 24 August, my father went to see a good friend of his, a Hindu, who was a civilian doctor. There were rumours in the market that there was going to be trouble and we Hindus were advised to leave. But my father’s friend was adamant he wasn’t leaving. Born in Murree, he had practised there for 40 years. The next morning, he was discovered in his house, lying dead in a pool of blood. My father decided to get the family out immediately. We left our house as it was.

I remember being made to lie on the floor of the truck because all along the 30-mile journey to army headquarters at Rawalpindi our vehicle was being fired on by snipers. Finally, we reached the army mess, where there was a military Dakota plane leaving for Delhi. My father managed to get my mother, myself, my younger sister and one of our servants on that flight. We sat on the floor alongside lots of soldiers, the family of a Sikh doctor and a number of sacks.

The day we arrived at my aunt’s in Delhi, her Muslim dhobi [washerman] staggered into the house clutching his abdomen. His stomach had been slashed and he was holding his intestines.

By September, trains were arriving from Pakistan full of dead bodies. My father and his Hindu colleague, Dr Basu, had joined a convoy of trucks from Rawalpindi to Delhi. They left around 29 August and we didn’t know whether they were dead or alive until the end of September, when my exhausted father arrived and told us about thousands of refugees and the River Jhelum, which had run red with blood. Dr Basu and my father, who was a surgeon, had operated on wounded people left by the road. They ran out of anaesthetic and catgut so they made do with ordinary thread. Luckily, they had a big canteen containing liquor, so they made patients drink it as anaesthetic and poured it on to wounds to stop infection.

I grew up and became a painter. It strikes me as strange that very little art came out of those experiences. I think we don’t want to remember.

Accounts of Sohinder Nath Chopra and Anjolie Ela Menon courtesy of the Partition Museum, Amritsar

Family waiting in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting

Four Hindus w. their belongs in gunny sacks, waiting for train at Howrah railroad station as they hope to escape to the villages to avoid the Muslim riots which are destroying their business & homes

Hindu

woman w. her children, eating one of their 2 daily meals of rice as

they take refuge from communal riots at relief station run by the Muslim

League at Lady Bradbourne College

Hindu

women & children eating one of their 2 daily meals of rice as they

take refuge from communal riots at relief station run by the Muslim

League at Lady Bradbourne College

Hindu

women & children eating one of their 2 daily meals of rice as they

take refuge from communal riots at relief station run by the Muslim

League at Lady Bradbourne College

Hindu

women & children eating one of their 2 daily meals of rice as they

take refuge from communal riots at relief station run by the Muslim

League at Lady Bradbourne College

Man carrying another man as they wait in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting

People waiting in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting

People waiting in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting

People waiting in railroad station trying to escape city after bloody rioting

People waiting in railroad station with their cows as they try to escape city after bloody rioting

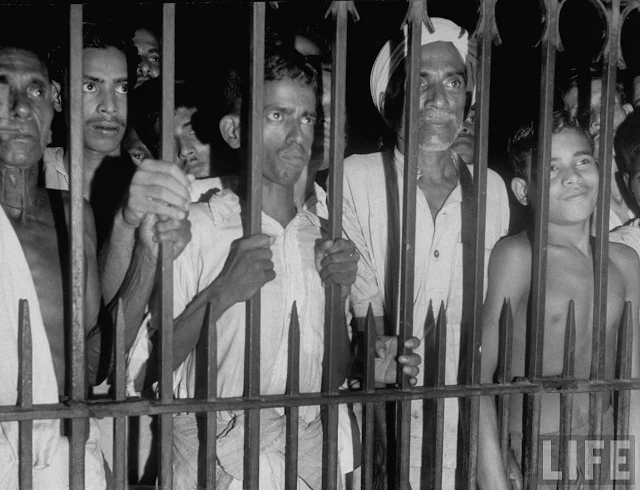

Throng

of Hindus crowding the ticket windows at Howrah railroad station as

they hope to escape to the villages to avoid the Muslim riots which are

destroying their business & homes

Women & children waiting for food in ration line after bloody rioting

Women

in a rickshaw passing evacuees streaming across the Howrah Bridge on

their way to the railway station in hopes of escaping the city after

bloody rioting - Calcutta (Kolkata) August 1946

Source: Life Archive hosted by Google

Photographer: Margaret Bourke-White

Muslim refugees attempting to flee India sit on the roof of an overcrowded train near Delhi in September 1947.

Photograph: AP

Muslim refugees attempting to flee India sit on the roof of an overcrowded train near Delhi in September 1947.

Photograph: AP ‘It was a time when the normal mores of civilisation were suspended’ ... Moni Mohsin. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the GuardianEverywhere I went in Delhi I heard similar stories, but that is not

surprising. At partition, Delhi received a huge influx of Hindu and Sikh

refugees from Punjab. Some moved on to other parts of India, but most

stayed and put down roots. In the 90s, many of those elderly migrants

were alive; whenever I bumped into them and they heard I was from

Lahore, they crowded round, asking me to speak in “real Lahori Punjabi”.

Others asked after childhood haunts they hadn’t seen for almost 50

years –

‘It was a time when the normal mores of civilisation were suspended’ ... Moni Mohsin. Photograph: Sarah Lee for the GuardianEverywhere I went in Delhi I heard similar stories, but that is not

surprising. At partition, Delhi received a huge influx of Hindu and Sikh

refugees from Punjab. Some moved on to other parts of India, but most

stayed and put down roots. In the 90s, many of those elderly migrants

were alive; whenever I bumped into them and they heard I was from

Lahore, they crowded round, asking me to speak in “real Lahori Punjabi”.

Others asked after childhood haunts they hadn’t seen for almost 50

years –