COOLIE SLAVERY IN THE BRITISH COLONIES.

The British government emancipated the negro

slaves held under its authority in the West Indies,

thereby greatly depreciating the value of the islands,

permitting a half-tamed race to fall back into a state

of moral and mental darkness, and adding twenty millions

to the national debt, to be paid out of the sweat

and blood of her own white serfs. This was termed a

grand act of humanity; those who laboured for it have

been lauded and laurelled without stint, and English

writers have been exceedingly solicitous that the world

should not "burst in ignorance" of the achievement.

Being free, the negroes, with the indolence inherent

in their nature, would not work. Many purses suffered

in consequence, and the purse is a very tender place to

injure many persons. It became necessary to substitute

other labourers for the free negroes, and the

Coolies of India were taken to the Antilles for experiment.

These labourers were generally sober,

[Pg 434]

steady, and industrious. But how were they treated?

A colonist of Martinique, who visited Trinidad in

June, 1848, thus writes to the French author of a

treatise on free and slave labour:—

"If I could fully describe to you the evils and suffering endured

by the Indian immigrants (Coolies) in that horribly governed

colony, I should rend the heart of the Christian world by a recital

of enormities unknown in the worst periods of colonial

slavery.

"Borrowing the language of the prophet, I can truly say,'The

whole head is sick, and the whole heart is sad; from the sole of

the foot to the top of the head nothing is sound;' wounds, sores,

swollen ulcers, which are neither bandaged, nor soothed, nor

rubbed with oil.

"My soul has been deeply afflicted by all that I have seen.

How many human beings lost! So far as I can judge, in spite

of their wasting away, all are young, perishing under the weight

of disease. Most of them are dropsical, for want of nourishment.

Groups of children, the most interesting I have ever seen,

scions of a race doomed to misfortune, were remarkable for their

small limbs, wrinkled and reduced to the size of spindles—and

not a rag to cover them! And to think that all this misery, all

this destruction of humanity, all this waste of the stock of a

ruined colony, might have been avoided, but has not been!

Great God! it is painful beyond expression to think that such a

neglect of duty and of humanity on the part of the colonial authorities,

as well of the metropolis as of the colony—a neglect

which calls for a repressive if not a retributive justice—will go

entirely unpunished, as it has hitherto done, notwithstanding the

indefatigable efforts of Colonel Fagan, the superintendent of the

immigrants in this colony, an old Indian officer of large experience,

of whom I have heard nothing but good, and never any

evil thing spoken, in all my travels through the island.

"I am told that Colonel Fagan prepared a regulation for the government

and protection of the immigrants—which regulation

[Pg 435]

would probably realize, beyond all expectation, the object aimed

at; but scarcely had he commenced his operations when orders

arrived from the metropolis to suppress it, and substitute another

which proceeded from the ministry. The Governor, Mr. Harris,

displeased that his own regulation was thus annulled, pronounced

the new order impossible to be executed, and it was withdrawn

without having been properly tried. The minister sent another

order in regard to immigration, prepared in his hotel in Downing

street; but Governor Harris pronounced it to be still more difficult

of execution than the first, and it, too, failed. It is in this

manner that, from beginning to end, the affairs of the Indian

immigrants have been conducted. It was only necessary to treat

them with justice and kindness to render them—thanks to their

active superintendent—the best labourers that could be imported

into the colony. They are now protected neither by regulations

nor ordinances; no attention is paid to the experienced voice of

their superintendent—full of benevolence for them, and always

indefatigably profiting by what can be of advantage to them.

If disease renders a Coolie incapable of work, he is driven from

his habitation. This happens continually; he is not in that case

even paid his wages. What, then, can the unfortunate creature

do? Very different from the Creole or the African; far distant

from his country, without food, without money; disease, the

result of insufficient food and too severe labour, makes it impossible

for him to find employment. He drags himself into the

forests or upon the skirts of the roads, lies there and dies!

"Some years since, the unfortunate Governor (Wall) of Gorea

was hung for having pitilessly inflicted a fatal corporal punishment

on a negro soldier found guilty of mutiny; and this soldier,

moreover, was under his orders. In the present case, I can prove

a neglect to a great extent murderous. The victims are Indian

Coolies of Trinidad. In less than one year, as is shown by

official documents, two thousand corpses of these unfortunate

creatures have furnished food to the crows of the island; and a

similar system is pursued, not only without punishment, but

without even forming the subject of an official inquest. Strange

and deplorable contradiction! and yet the nation which gives us

[Pg 436]

this example boasts of extending the ægis of its protection over

all its subjects, without distinction! It is this nation, also, that

complacently takes to itself the credit of extending justice equally

over all classes, over the lordly peer and the humblest subject,

without fear, favour, or affection!"

In the Mauritius, the Coolies who have been imported

are in a miserable condition. The planters

have profited by enslaving these mild and gentle

Hindoos, and rendering them wretched.

"By aid of continued Coolie immigration," says Mr. Henry C.

Carey,

[103]

"the export of sugar from the Mauritius has been doubled

in the last sixteen years, having risen from seventy to one hundred

and forty millions of pounds. Sugar is therefore very

cheap, and the foreign competition is thereby driven from the

British market. 'Such conquests,' however, says, very truly, the

London Spectator, 'don't always bring profit to the conqueror;

nor does production itself prove prosperity. Competition for the

possession of a field may be carried so far as to reduce prices

below prime cost; and it is clear, from the notorious facts of the

West Indies—from the change of property, from the total unproductiveness

of much property still—that the West India production

of sugar has been carried on not only without replacing

capital, but with a constant sinking of capital.' The 'free'

Coolie and the 'free' negro of Jamaica have been urged to competition

for the sale of sugar, and they seem likely to perish

together; but compensation for this is found in the fact that

'free trade has, in reducing the prices of commodities for home

consumption, enabled the labourer to devote a greater share of

his income toward purchasing clothing and luxuries, and has increased

the home trade to an enormous extent.' What effect this

reduction of 'the prices of commodities for home consumption'

[Pg 437]

has had upon the poor Coolies, may be judged from the following

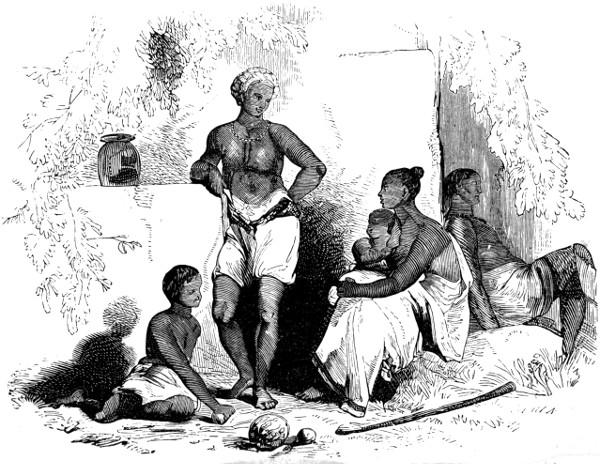

passage:—'I here beheld, for the first time, a class of beings of

whom we have heard much, and for whom I have felt considerable

interest. I refer to the Coolies imported by the British government

to take the places of the faineant negroes, when the apprenticeship

system was abolished. Those I saw were wandering

about the streets, dressed rather tastefully, but always meanly,

and usually carrying over their shoulder a sort of chiffonnier's

sack, in which they threw whatever refuse stuff they found in the

streets or received as charity. Their figures are generally superb,

and their Eastern costume, to which they adhere as far as their

poverty will permit of any clothing, sets off their lithe and graceful

forms to great advantage. Their faces are almost uniformly

of the finest classic mould, and illuminated by pairs of those

dark, swimming, and propitiatory eyes which exhaust the language

of tenderness and passion at a glance. But they are the

most inveterate mendicants on the island. It is said that those

brought from the interior of India are faithful and efficient workmen,

while those from Calcutta and its vicinity are good for

nothing. Those that were prowling about the streets of Spanish

Town and Kingston, I presume were of the latter class, for there

is not a planter on the island, it is said, from whom it would be

more difficult to get any work than from one of them. They subsist

by begging altogether. They are not vicious nor intemperate,

nor troublesome particularly, except as beggars. In that calling

they have a pertinacity before which a Northern mendicant would

grow pale. They will not be denied. They will stand perfectly

still and look through a window from the street for a quarter of

an hour, if not driven away, with their imploring eyes fixed upon

you like a stricken deer, without saying a word or moving a

muscle. They act as if it were no disgrace for them to beg, as if

an indemnification which they are entitled to expect, for the outrage

perpetrated upon them in bringing them from their distant

homes to this strange island, is a daily supply of their few and

cheap necessities, as they call for them. I confess that their

begging did not leave upon my mind the impression produced by

ordinary mendicancy. They do not look as if they ought to

[Pg 438]

work. I never saw one smile; and though they showed no positive

suffering, I never saw one look happy. Each face seemed to

be constantly telling the unhappy story of their woes, and, like

fragments of a broken mirror, each reflecting in all its hateful

proportions the national outrage of which they are the victims.'"