Happy hundredth, Daddy Cool

Updated on: 05 May,2024 07:30 AM IST | Mumbai

Meher Marfatia

Celebrating the life and times of a parent who passed on five years short of a century of amazing grace

At a concert finale in 1995 with violin teacher Kenneth D’Souza at centre

Were he alive, Homi Dastoor would have been 100 last weekend. What better way to wish a century-hitting father than recap vignettes from an exceptional life, close to family and friends, to music and books.

Were he alive, Homi Dastoor would have been 100 last weekend. What better way to wish a century-hitting father than recap vignettes from an exceptional life, close to family and friends, to music and books.

Our parents, and the extended joint family they shepherded, redefined goodness.

My brother and I heard this phrase a lot while growing up: “Jamno haath su karey tey dabho haath nai jaaney–what the right hand does, the left cannot tell.” Simply put, give quietly. News of a multitude of kindnesses to people from both parents keep reaching us years after we lost them, Mum 15 years ago and Dad, five.

Playing the violin for his wife Homai and a young Zarir

Playing the violin for his wife Homai and a young Zarir

What do you do when you outlive loved ones as the long arc of time stretches, I once asked. “Immerse yourself in the arts,” he suggested. “Books and music are gifts allowing you to appreciate every experience the world holds. Any creative composition has the power to move you, matching every emotion and mood.”

Generous to a fault, he could not bring himself to ask back for borrowed books or vinyl records friends failed to return. Giving not the slightest reminder, he said, “They haven’t forgotten, they obviously like it enough to keep it.” We may not have agreed.

But that was him.

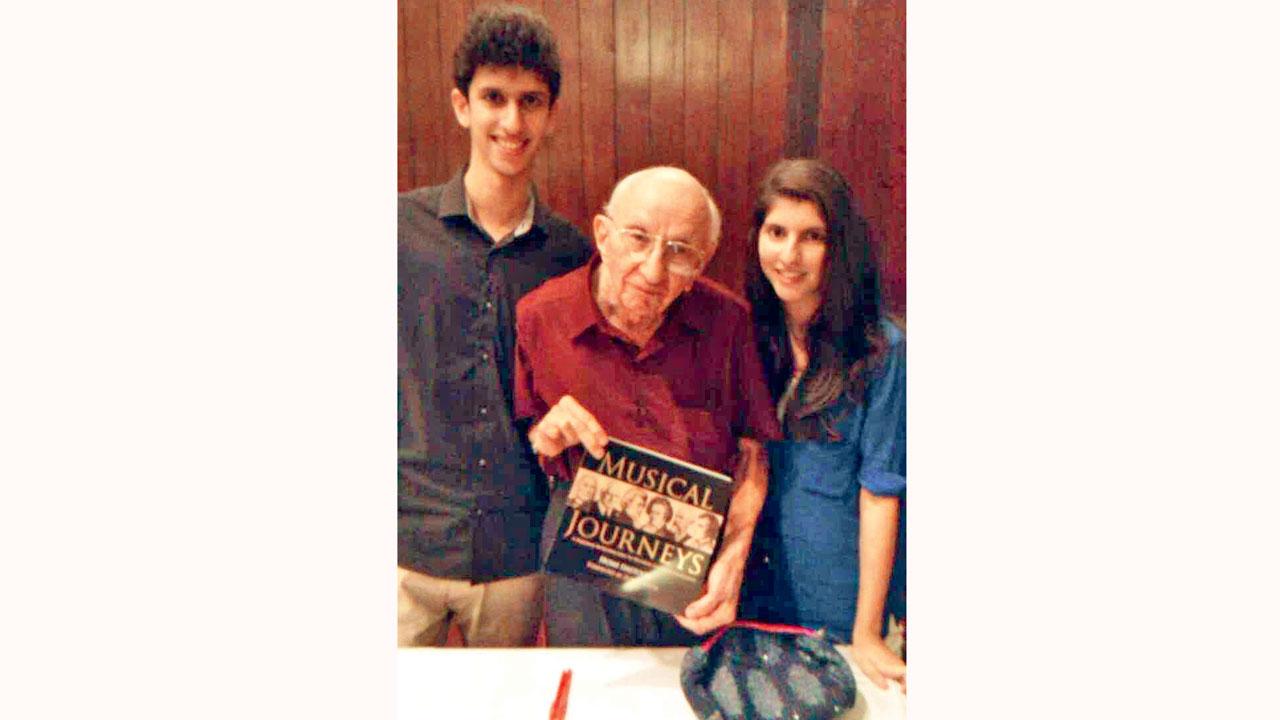

Homi Dastoor with grandchildren Zarir and Ayesha at the NCPA launch of Musical Journeys, the book he authored in 2014 at age 90

Homi Dastoor with grandchildren Zarir and Ayesha at the NCPA launch of Musical Journeys, the book he authored in 2014 at age 90

Apart from friends he exchanged books with and friends he listened to music with, there were the companions he travelled daily with. In that wonderful mode of transport called the contract bus. A contract bus carried a whole culture with it, as passengers trailed to offices across town and back, assured of a comfortable seat plus much fun on the run. The 1970s to the ’90s saw hordes of these heavy vehicles lumber noisily, bridging the city’s north-south divide.

Fellow travellers thrown together soon reaped cool camaraderie. “CB pals” like adman Devjit Kohli, doctor Maneck Engineer and journalist Sherna Gandhy remained Dad’s friends for decades. Driving a car to work from 1990, Kohli sorely missed the regular earlier ride. He remembers: “I treated the bus like my private limo. The parking point during the day was Ballard Estate. If I had an appointment with, say, Bombay Dyeing in the neighbourhood, I left papers and parcels on the bus rather than carry them.”

Finding it impossible to get a foothold on peak hour-packed trains, Gandhy chose the contract bus. She recalled the citywide blackout in the early ’80s cause total traffic gridlock. “Commuters stranded solo were petrified in the dark. On the bus from 5 to 11.30 pm, we didn’t panic. In fact, there was some clowning around, especially Homi with his corny jokes.” And Engineer declared, “We were family. It was refreshing to climb the bus and be with each other for respite after a hard day’s grind.”

With “contract bus” friends at a Gorai picnic in the 1990s

With “contract bus” friends at a Gorai picnic in the 1990s

There was room for small intimacies too. If he couldn’t inform his wife that he would be late (no cell phones trilled then), Kohli’s message was relayed by the bus cleaner, his stop being outside their apartment. Mornings saw some finish reciting prayers on the bus before settling to avid gossip and banter. Entertaining diversions ensued, like watching romances bloom between the rows. One audacious Lothario two-timed women mere seats apart. Wednesday evening “parties” onboard proved perfect midpoints to bust the buildup of weekly work stress. They came complete with chocolate cake and crisps (the Dastoor contribution was wafers from Blue Circle outside New Talkies), games and gags.

Returning home, there was barely an evening Dad spent sans music. Besides being engrossed in LP after LP for hours, he demystified the intimidating Western classical genre, by drawing parallels between musical compositions and scenes from everyday life. From adagio rising to allegro, he happily explained music as metaphor.

Remarkably linking everyday episodes and contemporary scenes to an appreciation of Beethoven. Sighting full moon shimmer on the Arabian Sea waters when we visited the Bandra Band Stand on Sundays, he hummed the first movement of the Moonlight piano sonata, telling us how the poet-critic Ludwig Rellstab likened its effect to the moon shining on Lake Lucerne. After I returned from attending a journalism course in Berlin in the summer of 1989, the historic Wall dismantled that November. To honour the occasion, Dad explained, that Christmas Day was to witness Leonard Bernstein conduct the Ninth Symphony’s exultant rendition of Schiller’s Ode to Joy.

Retiring from Bombay House, following a long innings at Tata Textiles, Dad decided to pick up the violin for the first time. At 65, encouragingly tutored by 23-year-old Kenneth D’Souza who was with the Bombay Chamber Orchestra. “I think I could still do this,” Dad remarked, touching bow to strings.

D’Souza mails me from New Zealand: “I am eternally grateful for the opportunity of teaching Homi. I marvelled at his goal with a bit of scepticism but gave him credit for abounding enthusiasm. The very morning after the office farewell, he arrived with his violin case and a cake, informing me earnestly that despite his bent back, arthritis and weakening vision, he was keen to fulfil his dream of playing the violin. His musical journey of eight fulfilling years taught me a great rewarding lesson: never underestimate learning music at any age. Homi showed the ability to compensate for physical hindrances with alternative routes. Finding it difficult to read score sheets with failing eyesight and stooping spine issues, he memorised pieces. It was a huge learning curve for me in the process of overcoming challenges.”

To coax sharp notes from that tough musical instrument at a stage when the fingers start gnarling was rough on him and us. Not easy, those grating-screechy practice hours. Blindly supportive, Mum rallied him on–“Lovely, dear, carry on,” while we hoped our pained grimaces went unnoticed.

Nor did Dad think it extraordinary to write a magnificent book on music at 90. Solitarily, slowly, writing chapters of neat manuscript in firm longhand, with no computer or dictated text, he researched with meticulous determination well into the night. Eyes fatigued, yet mind fired.

It was Beethoven he lay gently with in his final evening on earth. Lighting the traditional divo near his head, I deliberated–which Avesta verses needed to be chanted till the priest arrived? My childhood friend Himanshu resolved the matter, saying, “Music was prayer for Homi Uncle. Let him have his Beethoven.”

He did. From the sonorous Appassionata piano sonata to the magisterial violin concerto in D Major. The situation confounded neighbours receiving news of his death. Every evening Mr Dastoor listened to music as a matter of routine. There it was, blaring forth as usual. Puzzled, gingerly they ventured to ask, was what they heard true?

The cadenced calm and abiding grace of that night will always remain with me. Mere hours after he expired, our son wrote this: “Homi Dastoor was a man of impeccable manners, a proper gent. He could not fathom lies, underhanded behaviour or greed. A man of modest means, he dedicated his entire savings (which weren’t much) to the well-being of his family, which included taking care of three elder unmarried sisters, whom he graciously shared his house with.

“His only indulgence was music. Some friends comment on my ‘ancient’ music preferences. They don’t have grandfathers who worshipped iconic classical composers. Most people lose their passions, drowned beneath obligations of work and other mundane tasks. Not Homi. He kept the fire burning, taking up the violin post-retirement, writing his beautiful book at 90, the pinnacle of his life.

“Gramps taught me too many things to list. Here are my top 4. First, manners. There is no cost to being a gentleman. Years of what used to be called ‘a good upbringing’, followed by working as Darab Tata’s executive assistant, formed the bedrock for his social skills, displayed till before he just passed, when he opened his eyes after a seizure for a few seconds to appreciate the doctor for administering to him–‘Thank you doctor for coming, but I am going.’ Polite and prescient to the end.

“Secondly, to not take life too seriously. Why get bogged down when there is a world full of music and laughter to be explored? Everyone knew Homi for his jokes. Some of which would definitely raise eyebrows today, but were told with such clean heart and good nature that they drew grudging grins from my politically correct sister.

“Thirdly, what real love means. Love in health, but more so in sickness. He married my grandmother despite being warned by her own father that she had a potentially difficult illness to manage. It was the best decision he ever made.

“Lastly, perhaps most importantly, let life run its course. Don’t compare yourself to others or believe it’s too late to achieve what you really want. He managed to do what he loved at 90. If we are lucky to discover this feeling a few years before him, he’d have a smile on his face. The same smile worn by anyone who had the pleasure of his company. Rest in peace, Papa. We love you.”

Author-publisher Meher Marfatia writes fortnightly on everything that makes her love Mumbai and adore Bombay. You can reach her at meher.marfatia@mid-day.com/www.meher marfatia.com