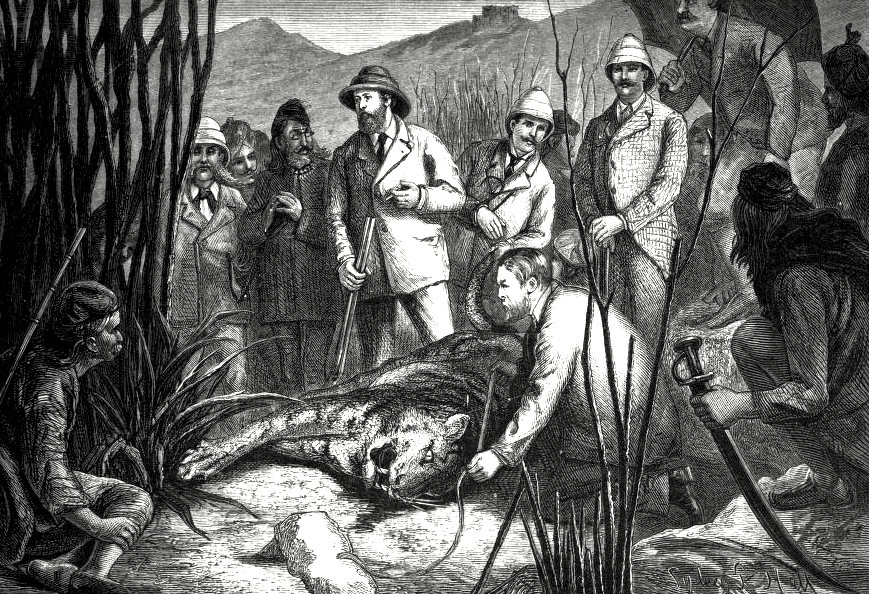

The Prince's First Tiger. Source: Russell, facing p. 458. This and subsequent illustrations from Russell are by Sydney P. Hall (1842-1922), the official artist on the tour. The Prince stands in the centre, cigarette in one hand, rifle in the other. His hunting gear in India consisted of "a khaki jacket and knickerbockers and a solar topee with a very wide brim," sometimes with the addition of "leech gaiters" (The Private Life, 253). Even in this wild rocky area, it included a tie as well. He was particular as to dress.

The Prince's First Tiger. Source: Russell, facing p. 458. This and subsequent illustrations from Russell are by Sydney P. Hall (1842-1922), the official artist on the tour. The Prince stands in the centre, cigarette in one hand, rifle in the other. His hunting gear in India consisted of "a khaki jacket and knickerbockers and a solar topee with a very wide brim," sometimes with the addition of "leech gaiters" (The Private Life, 253). Even in this wild rocky area, it included a tie as well. He was particular as to dress.

Shooting expeditions, balls and visits to Maharajahs punctuated the rest of the stay here, which also included a trip to Jaipur, where the Prince shot his first tiger, or, rather, tigress. "That the tigress on being skinned is found to have been the prospective mother of three cubs, is considered a matter for farther rejoicing," says one commentator, without intimating (except perhaps in the distance implied by "is considered") his own feeling on the matter (Gay 320). In fine fettle, the Prince later smoked a hookah at the Maharajah's banquet. Whilst based at Agra, too, the Prince "saw a great deal," and probably a great deal too much, of his host Lord Strachey's young sister-in-law, Mabel Batten, who was only nineteen and just recently married. It was the kind of thing the Queen, and no doubt his wife, the future Queen Alexandra, had feared, but it did not become a scandal. On the other hand, it was widely noted in his favour that the Prince had shown his displeasure when a rajah was treated discourteously by one of the officials (see Ridley 179-80). Here was another example of his good nature and the genuine appreciation he showed his hosts.

The Terai

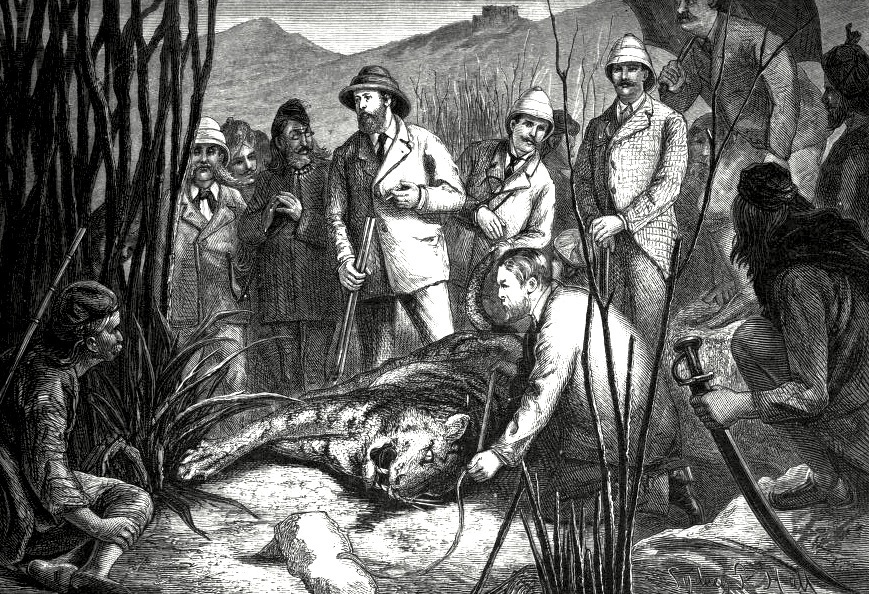

Left: The Himalayas at Sunrise. Source: Russell, facing p. 466. Right: The Pleasures of the Chase. — Pad Elephant. Source: Russell, facing p. 490. Hall himself had captioned this one, "A Wild Elephant Chase in Nepal." Russell explains that the hot and weary elephants were cooling themselves with showers from their trunks, and that the Prince himself came in for a sudden soaking.

The last part of the Prince's tour was spent in the Terai, in the Kumaon Hills, famous for their man-eating tigers. While the Serapis sailed for Bombay in readiness for the voyage home, the Prince took one last view of the Taj Mahal by moonlight, and left Agra by his special train for Moradabad, at the end of its line in that area. "Dreaming possibly of the Taj, or of the pleasant camp and the hospitalities of Sir John and Lady Strachey at Agra, stretched at length on the comfortable cushions of our railway carriages, and snugly wrapped in resais [quilts]" (Russell 463), a select party was wafted away further north, to spend the middle of February at the vast hill-camp of Sir Henry Ramsay, and engage in big-game hunting. After a visit to the pretty hill-station of Nainital, where the Prince and some members of the party went to a well-known vantage point to see the snowy range at sunset, came a longer one to Nepal:

The Nepaul Terai is a vast land of jungle interspersed with woods of great trees, and broken by hills, ravines, nullahs, and sluggish streams. It is the rearing home for wild beasts, and birds of every known and unknown kind. The streams which flow from the watershed of the Gundra ridge on the south, and from the snows of the Himalayas, here the highest peaks in the world, enter into the beautiful valley of Nepaul,and form three great tributaries of the Ganges. [Wheeler 319]

Here the sport was excellent and the Prince soon bagged the first of many more tigers, including a tigress pregnant with six cubs (see Russell 458). This makes difficult reading now, and even at the time the Graphic made a point of devoting some lines to the Prince's affection for his elephant, to which he would give "bread, cakes, fruit &c" in the morning, and which, in return, would salute him with its trunk (202). But, on the whole, it would be a mistake to denigrate the Prince's sporting pursuits in India: attitudes were very different then. "There can be no doubt," wrote one biographer with a special interest in the Prince's prowess in this area, that "the skill and adroitness with which His Royal Highness adapted himself to entirely new surroundings, particularly in the Terai, and the success which happily attended his efforts, had their effect on all classes of the Indian community" (Watson 341-42). This biographer noted the Prince's courage, too. It might be added that his entourage included a naturalist (Mr Bartlett) as well as a botanist (improbably named Mr Mudd), for whom the Prince's various trophies were specimens for a future collection.

Then the homeward journey began. Although there were more grand receptions en route, particularly at Allahabad where another investiture was held, and at Lalbagh, where a durbar was held, there was a clear feeling of winding up a fabulous stay. On 11 March they reached Bombay again, and were received on board the waiting and freshly painted Serapis with all due formalities, and expressions of appreciation for all that had been done, and regret at the departure, on every side. "The Prince has travelled nearly 7600 miles by land and 2300 miles by sea, knows more Chiefs than all the Viceroys and Governors together, and seen more of the country in the time than any living man," noted Russell (520-21).

Consequences

Left: The Prince of Wales in the frontispiece to Russell's book. Right: Sir William Howard Russell (1820-1907) from the Times, who had exclusive reporting rights for the trip (see Ridley 174), and, as the Prince's private secretary on the tour, was the best able to convey every aspect of it. © The National Portrait Gallery.

The second Times leader of 6 March 1876 pointed out the cumulative effect of all the reports that had poured out of India in the last few months. Previously, the British press had been apt to focus on the "troublesome financial problems" that the country presented. But the Prince's tour had now brought out for the British public the "dazzling accumulation of natural marvels, great traditions, wealth, and historic influence" of the sub-continent. For his part, the Prince of Wales had, it seems, impressed upon the Indian Princes the fact that they were now "members of an organised Empire," and had had "the tact, or rather the generosity and the good feeling, to bring this reality home to them." In this respect, "the pomps and shows of a Royal progress, the grace of a Royal visit" had had "permanent value in what they [implied]." They formed, as Russell said on one occasion in his published book on the tour, a "tangible, visible representation of royalty" (341).

Partly thanks to Russell's own literally glowing reports, during the Royal progress the Prince had emerged convincingly, to the public at home as well as to the people of India, as "the future Suzerain of ancient dynasties." It had all been a resounding diplomatic triumph, one upon which the leader-writer himself (whether Russell or the editor taking his cue from him) urged the government to capitalise. Indeed, in pushing for the title of Empress of India, Queen Victoria was already doing her utmost in this regard — perhaps partly out of a desire to steal a march on her son (see Ridley 181). There was, however, a clear note of warning in the leader as well. "If we continue to regard the heirs of that vast civilisation as conquered dependents, a feeling of alienation will slowly but surely deepen." With evident relish, Bertie had done his best for relations between Britain and India. Now it was up to his successors to build on the close ties he had created, or ultimately to destroy them.

Related Material

- Bertie's Progress: Part I

- The Prince of Wales's Saloon Carriage

- Royal Titles Bill (Second reading)

- New Crowns for Old Ones (John Tenniel's cartoon lampooning the Royal Titles Bill)