Life's a beach – then you're the comms nexus of the British Empire and Marconi-baiting hax0rs

Inside Porthcurno's world-spanning telegraphy web

But this place is important, and has been for a long time. There are bunkers in the cliffs, paths with numerous manhole covers and a diamond-shaped yellow sign. And on top of a sand dune next to a lifeguards' hut is what appears to be a windowless white cube.

When it is open you can peer through the building's grated door at an array of decades-old electronics, with labels including Fayal, Gibraltar and Old Vigo. It is Porthcurno's Cable House, built in 1929 and housing the ends of 14 international cables.

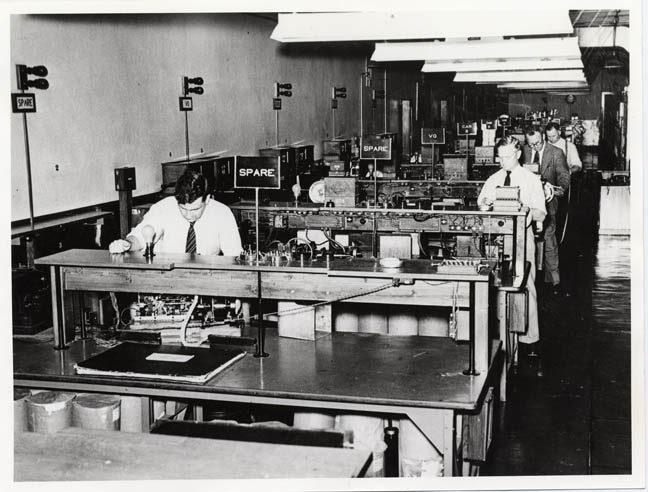

Discreet presence ... The telegraphy station at its apex in 1947. Photo: Telegraph Museum Porthcurno

Telegraphy combined Hans Christian Ørsted's discovery of electromagnetism and Samuel Morse's signalling instrument and code. Electrons were fired down undersea cables protected by gutta-percha, a substance made from the sap of the Malayan percha tree for insulation.

Porthcurno was the spot chosen by Victorian businessman John Pender as landfall for a burgeoning network of global undersea cables serving this new medium that would, quickly, come to span not just the British Empire but the planet.

At its height, during the Second World War, the telegraphy web Pender founded traversed 355,000 miles and shot messages across continents in a matter of minutes rather than the weeks it had taken to send letters by boat.

By 1944, the equivalent of the entire works of Shakespeare flowed through this valley every 11 hours, making Porthcurno arguably the most important telecommunications facility in Britain.

Porthcurno was also the site of what may have been the first act of wireless hacking and espionage. It was on Cornwall's Lizard Peninsula, a few miles to the east, that Guglielmo Marconi – whose ideas were ignored by his own government – was pushing the boundaries of wireless in his attempt to send the world's first transatlantic wireless signal.

Pender's people erected their own mast to spy on Marconi's and attempt to to crack his message stream.

Porthcurno stopped operating in 1970 but its role as a communications-landfall site continues: today, terabits of data flow through fibre-optic cables beneath this beach, linking Britain to the rest of the world.

The operators of such vital infrastructure tend to prefer it remains obscure. But Porthcurno's Telegraph Museum, housed up the valley in what was once the world's biggest telegraph station, lifts the lid on how important this sleepy valley in Cornwall has been for more than century.

Hello Gibraltar ... The cable house cables. Photo: SA Mathieson

The museum is divided into two sections. The first, in the upper floor of the main building, provides a wealth of information on the story of cable-based telecommunications and Porthcurno's role therein. It does so through a short and informative video, vintage equipment, displays and interactive equipment – the primary school children visiting when I was there made particularly audible use of the Morse code generator.

It's a great story, starting in earnest with the invention of telegraphy in the 1830s and the first international submarine cable being laid from Dover to Cap Gris-Nez near Calais in 1850, then failing within a few hours. This was later blamed on a French fisherman thinking it was a new type of seaweed, although contemporary accounts suggest it simply broke in the tide. A working replacement was installed the following year.

After three failed attempts, the first reliable transatlantic cable was laid in 1866 by the Atlantic Telegraph Company. The work was led by Pender, who made his money in textiles and became a fundraiser and investor having been involved in the first Anglo-Irish cable in 1853.

Porthcurno's tunnels, dug and built in just 10 months to withstand a bomb blast. Photo: Telegraph Museum Porthcurno

On 23 June 1870, Porthcurno was telegraphically linked to Mumbai, then named Bombay. The initial cost of sending a message was £4, equivalent to more than £400 today, but it arrived in nine minutes, rather than the six weeks it would take by ship. Pender merged various telegraphy companies into the Eastern Telegraph Company and expanded his network. By 1880 the company controlled nearly 100,000 miles of undersea cable, centred on Porthcurno and reaching as far as Australia.

The exhibits include lots of technological details, such as how this low-bandwidth network compressed messages: a panel says a Harry Potter book would take 74 days to transmit by telegraph, compared with 0.000006 seconds by fibre-optic cable. The company had a list of numbers to replace often-used strings of words, including some quite specific ones such as 120 for: "I wish we were together on this special occasion all my best wishes for a speedy reunion," and 136 for: "Hearing your voice on the wireless gave me a wonderful thrill."

Porthcurno had been almost uninhabited before the telegraph, but by 1877 the station employed four married men and 32 bachelors. They called themselves "exiles" – the valley was inaccessible by motor vehicle until the 1900s – a name that was picked up by telegraph operators worldwide. Exhibits suggest they played a lot of sport, hence those tennis courts out front, and indulged in amateur dramatics – a photo of two (male) exiles shows them playing Antony and Cleopatra.

In 1900, Marconi came to the Lizard Peninsula, building 20 masts at Poldhu 60.96m (200ft) high, connected to a 25kW transmitter. These were blown down by high winds, so it was a pair of temporary 48.76m (160ft) masts that sent the first transatlantic wireless signal in December 1901, to Newfoundland in Canada.

The Eastern Telegraph Company decided to spy on Marconi and so set up its own 48.76m mast to listen in, employing the skills of a wireless enthusiast and magician named Nevil Maskelyne.

The Elliott Brothers' regenerator synchroniser, photo: SA Mathieson

Articles in a journal are one thing, but a public humiliation gets more attention so, in 1903, Maskelyne hacked a demonstration by electrical engineer and physicist John Ambrose Fleming at London's Royal Institution. Fleming was a consultant to the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company.

Waiting for signals from Poldhu, Fleming instead received the word "rats" in Morse. Maskelyne, who was transmitting from his father's nearby music hall theatre, followed this up with: "There was a young fellow of Italy, who diddled the public quite prettily." He then wrote to The Times to claim the hack, justifying it by saying it showed how flawed wireless "security" was.

But such antics did little to damage wireless, and the competition from Marconi began to take its toll on cable telegraphy. "The government at the time could see that the Eastern Telegraph Company was going to go under if it took so much business from it," said Gareth Parry, chair of the museum charity's trustees and an emeritus professor at Imperial College London.

Worried about losing its empire-spanning cable system, the government engineered a merger with Marconi's wireless operation, producing Cable & Wireless in 1934. The museum houses Cable & Wireless's corporate archive in a recently built education centre and library.

Demonstrating the military importance of fast, long-distance communications, one of the first actions by the British during the First World War was to cut most German-run undersea cables. Germany fought back, and the exhibition includes a knife used to cut what was actually a dummy cable on the Cocos Islands in the Indian Ocean. Times change, but the issues remain the same, and Britain remains vulnerable to similar sabotage – only now from Russia.

But Porthcurno's finest hour came in the Second World War. By then it was the world's largest telegraph station in a well-known location just 80 miles north of the Axis powers. It had to be protected – and the way this was achieved houses the second part of the museum.

Visitors leave the main building and enter a narrow tunnel into the nearby rockface, pass an unexploded Nazi bomb, open a door and travel back in time. In 10 months during 1940-41, miners from Cornwall and the West Indies removed 15,000 tonnes of rock to create two large tunnels, designed to protect Porthcurno's equipment and people. There is a 119-step emergency staircase to fields above, which the energetic are welcome to climb.

Landing the Gemini cable at Porthcurno. Photo: Telegraph Museum Porthcurno

The gear shows how much telegraphy had developed since Victorian times. The company had introduced "regen" in 1923, which replaced staff relaying messages en route with equipment that regenerated the strength and precision of signals every 200 miles or so.

Its relay stations replaced large numbers of operators with a few skilled engineers, and team games gave way to singles tennis. The equipment on show today shows how the highly automated regen process worked, from an originating station such as Cape Town via relays in locations including St Helena and the Azores to London.

Porthcurno, the place where the cables met, acted as the key repeater station on the way to the capital, but it had a further role: if Cable & Wireless's London office had been destroyed, these tunnels would become the central operating station of its entire 355,000-mile network.

Although that didn't happen, on some occasions the landlines failed, making Porthcurno the endpoint of the network with staff working around the clock to process messages. A 1944 letter on display discusses the continuing need to refuse space for evacuees, which had been the subject of local criticism, as the company might need to house 58 extra staff at short notice.

The valley was a "protected place" – everyone including residents had to show papers to gain access. As well as the still-visible pillbox bunkers above the beach, a flame barrage was installed. The tunnels were justified – the area was bombed, although the only reported casualty was a cow. In 1944 Porthcurno relayed 705 million words, more than triple what it had handled in 1938.

The equipment stayed in these tunnels until Porthcurno processed its last telegraph in 1970, by which point it was well into its post-war life as a Cable & Wireless engineering college, teaching students from all over the world. Some lecturers used the kit for demonstrations, and when the college closed in 1993 they turned it into the nucleus of today's museum.

To keep this equipment working, the museum has a volunteer-run workshop that is open to visitors. When I visited, Barry Hill – who worked on the University of Nottingham design team that built the first MRI scanner – and computer technician Patrick Dunne were renovating an electro-mechanical regenerator synchroniser built in 1926 by Elliott Brothers of London. It is original Porthcurno equipment, salvaged then rebuilt in the 1970s. Hill reckons that when they finish, it should continue to work for another couple of decades.

The museum, too, is undergoing renovations, the results of which should be open in spring 2018. The tunnels will house a new exhibition on fibre-optics, developed with the involvement University College London and the University of Cambridge. Parry said it will cover wavelength multiplexing, which greatly increased the capacity of a cable by simultaneously sending several signals at different wavelengths of light. The museum also works with Vodafone, which took over most of Cable & Wireless in 2012. Meanwhile, there's a well-stocked gift and bookshop and a site café serving light lunches – yes, including pasties.

A dazzling past ... The Porthcurno Telegraph Museum. Photo: SA Mathieson

Once the home of Skewjack Surf Village, Britain's first surf school when it opened in 1971, this site is now very much closed.

Porthcurno is a centre for undersea telecommunications but is a long way from the rest of the UK. If you travel here, beyond the obvious sandy charms of this and other beaches of this region, there are plenty of reasons to extend your trip beyond simply the Telegraph Museum.

Porthcurno itself boasts the open-air clifftop Minnack Theatre, with shows from March to September. Sennan Cove, just north of Land's End, is one of Cornwall's best beaches with plenty of parking, cafés, a pub and its own surf school. The town of Penzance and St Michael's Mount, a historic castle on a tidal island, are a few miles east. Continuing around Mount's bay, the Lizard Peninsula offers more geek tourism opportunities for those interested in Marconi's pioneering work.

Or, you could just explore the history of cable telecommunications at Porthcurno's excellent museum then relax on its beach, imagining how those surf-dogs would react if they could hear all the cat videos zipping beneath their paws.