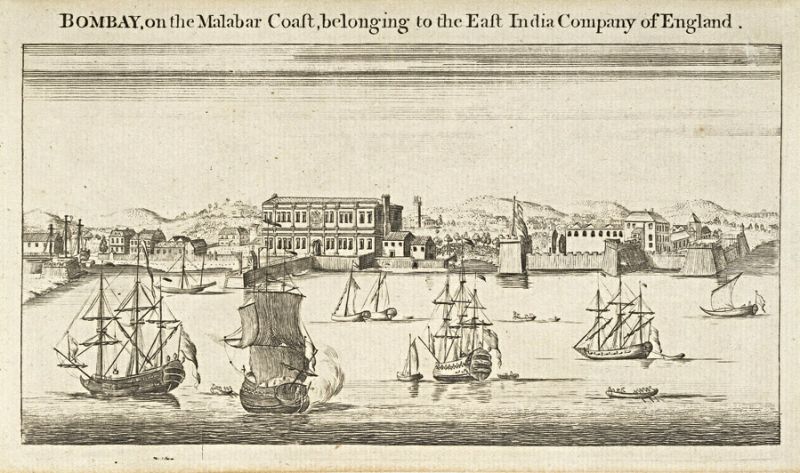

‘Bombay on the Malabar Coast, belonging to the East India Company of England’ dating circa 1754 to 1760, or just a few years prior to Carsten Niebuhr’s stay in Bombay. Line engraving by Jan Van Ryne. (Courtesy: British Library, Online Gallery, Print, P152).

Carsten Niebuhr in Bombay and Surat

Some of Niebuhr’s writings (1792) of that voyage survive and his son, the equally illustrious German statesman and financier, Barthold Niebuhr, wrote an account of his father’s life, published in 1828. In the last century, the Danish writer and voyager, Thorkild Hansen, compiled the available details of the expedition into a book (1962), and the New York Review of Books in June 2017 brought out an English translation by James McFarlane and Kathleen McFarlane.

Niebuhr and the Expedition

Born on 17 March 1733 in Ludingworth, Hanover, Germany, Niebuhr was orphaned in childhood and grew up in poverty. In his early youth, he worked in the fields, and by a chance encounter with a surveyor who was measuring land, Niebuhr too became interested in the subject.

At 20, he enrolled for a mathematics degree at the University of Göttingen, Germany. Around the time, King Frederik V of Sweden and Denmark enjoyed a reputation in Europe as a patron of the arts and sciences. One of Niebuhr’s professors suggested to the Swedish foreign minister that the king send an expedition to unknown lands, especially to places known since ancient times as Arabia Felix, “pleasant Arabia,” identified as Yemen but at that time also encompassing regions within present-day Arabia, Egypt and Syria.

Niebuhr applied to join the expedition as a surveyor and geographer and was accepted. For a year and a half, he worked hard to acquire some knowledge of Arabic.

The other members of the expedition were the Swedish natural scientist Peter Forsskål; the Danish philologist Frederik Christian von Haven, who would purchase oriental manuscripts for the Copenhagen Royal Library and transcribe inscriptions he came across; Niebuhr as cartographer would measure and map hitherto unexplored areas; the Danish physician Christian Carl Kramer would research a number of medical issues; the German artist and painter, Georg Wilhelm Baurenfeind, who would sketch the flora and fauna discovered and then there was the Swedish dragoon, Lars Berggren, the voyage’s man Friday.

In February 1761, the explorers left on board the Danish warship the “Grönland” and sailed from Copenhagen. Their journey took them via the Mediterranean to Constantinople, where they boarded another ship for Alexandria and Cairo. In Egypt, Niebuhr surveyed the Nile delta. His measurements and drawings were so detailed and exact that even a hundred years later, these were used in constructing the Suez Canal.

His colleague Forsskål discovered some 120 species of plants and collected seeds still unknown in Europe, while von Haven bought 72 manuscripts. Baurenfeind drew pictures of the way people lived—their tools, utensils and appliances, their traditional costumes and their musical instruments. They sailed from Suez in October 1762 and went on to Yemen, about which little was known in Europe, although numerous European ships had already docked in the port of Mocha or Al-Mokha to purchase the much sought-after coffee beans.

In Yemen, tragedy first struck. Travellers from cold northern Europe, the team, found itself helpless against the heat, the humidity and the ravages of the Anopheles mosquito. In May 1763, at Mocha, von Haven first died from malaria and Forsskål followed soon. To escape further mishaps, and to save the data they had amassed, the remaining members decided to travel eastward to India.

But in some ways, it was already too late; Baurenfeind and Berggren died on board in August 1763, while Kramer died in 1764 in Bombay. Carsten Niebuhr was henceforth left to work on his own, though he remained seriously ill for a long time with malaria himself. He spent nearly a year exploring Bombay and its environs before sailing homeward. He also spent some time in Surat.

Bombay, Almost a Perfect City

To travel unhindered in Bombay, Niebuhr wore local garb (loose cotton robes), and this proved effective. Bombay, as Niebuhr relates in his book translated in 1792, was then an island, “two miles in length, and more than half a mile in breadth” (p 388). A narrow channel divided it from another small isle called by the English, “Old Woman’s Island.” Bombay produced nothing but cocoa and rice, while on shore a considerable quantity of salt was also collected. The inhabitants were, thus, obliged to bring their provisions from the mainland, or from Salsette, a large and fertile island not far from Bombay that belonged to the Marathas.

Niebuhr writes of Bombay’s salubrious weather. The sea breeze and frequent rains rendered the climate temperate. Its air, Niebhur wrote, formerly unhealthy and dangerous, became purer once the English drained the marshes in the city and its environs.

The city was defended by a citadel in its middle that also overlooked the sea. The city had several handsome buildings; among which were the Director’s (as the head of the East India Company’s operations in Bombay was then called) palace, and a large and elegant church adjacent to it.

“The houses were not flat roofed as in the rest of the east but covered with tiles in the European fashion. The English had glass windows in their houses, while the other inhabitants had windows made of small pieces of transparent shells framed in wood” (p 390), that had the effect of making the apartments seem very dark. The harbour was spacious and sheltered. At the Company’s expense, Niebuhr learnt, two docks were hewn out of the rock, to enable two ships to anchor simultaneously. This was Bombay’s first beginnings as a sought-after port.

Niebuhr observed how the tolerance of English rule extended to people of all religions, a fact that rendered the island very populous. Its inhabitants numbered around 1,40,000 (Niebuhr’s precision for facts and numbers is apparent). Of these, the Europeans were the least numerous class. All religions, Niebuhr remarked, indulged in the free exercise of their worship, not only in churches, but openly, in festivals and processions, and none took offence at another.

Bombay was governed by a council comprising a governor called the president, and 12 counsellors, who were all merchants, except for the commander of the troops. The other employees of the East India Company were factors (trading agents) and writers (clerks) of different ranks.

Factors or trading agents were sent to interior settlements such as Sindh. The Company paid moderate salaries to its factors and directors, but they were permitted to trade on their own account in India from the Cape of Good Hope, to China, and northward, as far as Jeddah and Basra. By means of this extensive trade, “the directors were able to acquire the wealth which became the astonishment and envy of their countrymen in Europe.” However, these advantages were reserved for the English exclusively, for the Company did not admit strangers into the ranks of its merchants, though military service remained open. Niebuhr saw officers from various nations, especially Germans and Swiss.

Niebuhr noted how the coast from Bombay to Basra was infested by pirates. It might have been easy for the English to exterminate these pirates but “it was in the Company’s interest to leave these plunderers to scour the seas,” so as to hinder other nations sailing in the same latitudes. “The Indians dared not travel from one port to another, other than in convoys and under the protection of an English vessel, for which they were obliged to pay a high sum” (p 399).

Visiting Elephanta

Elephanta was a small isle, near Bombay, that then belonged to the Marathas. It was inhabited, Niebuhr wrote, by a hundred or so poor Indian families. Its proper name, he wrote, was “Gali Pouri,” but the Europeans called it Elephanta, from the statue of an elephant made of black stone, that stood on the island’s shore. This island was of small importance to the Marathas and so the English could visit it without passports. Niebuhr found the temple at Elephanta so remarkable that he visited the island three different times, to draw and describe its curiosities.

“The temple was a hundred and twenty feet long, and the same in breadth, without including the chapels and the adjacent chambers. Its height within was nearly fifteen feet, though the floor appeared higher due to the accumulation of dust, and the sediment left by the rains.” This vast structure was cut out of solid rock. The pillars supporting the roof were also hewn out of rock. The temple walls were “sculpted with figures in bas-relief and many of these figures were of colossal size; ranging from 10 to even 14 feet in height.”

Neither in design, nor in execution, Niebuhr specifies, could these bas-reliefs be compared with the works of the Grecian sculptors, but they were greatly superior to the remains of ancient Egyptian sculpture. Yet, he had little hope of obtaining any information from the island’s current inhabitants. “For they were simple folks who believed that strangers visited the island one night and raised this edifice by the time day broke” (p 410).

The headdress on some female figures was usually a high-crowned bonnet. Niebuhr observed also a turban on some statues. He also noted at several places, the image of the famous “Cobra de Capella,” a sort of serpent, that the inhabitants treated with great reverence. The smallest of the chapels had the sculpted figure of the God Gonnis (Ganesha), then still in a state of neat preservation.

The rest of the temple was in a state of utter neglect and haunted by serpents and beasts of prey. One did not dare enter without first firing several rounds of ammunition to scare them away.

Surat’s Peculiarities

Niebuhr went on to spend a few weeks in Surat. The common language was Persian, though Portuguese had come to be the language of commerce and business. The English counsellor at Surat had to announce, via the firing of a cannon, the “Mussalman festival of Bairan”—something that Niebuhr found unusual. He describes the various castes in Surat, the most proliferate being the “Hindoo Baniyas.” There were other groups, such as the Persians, Armenians, Jews and Georgians (from Georgia in Central Asia). He noticed the people’s predilection in announcing their wealth from the state of their palanquins and horse-drawn carriages, locally called “gharris.” Niebuhr bemoaned the presence of fakirs and wandering mendicants on every street, many of whom would refuse to vacate a house’s precincts until the host made a token payment in alms.

Learning from Travel

On his return journey, Niebuhr lingered for a time amongst the ruins at Persepolis in Iran, destroyed by Alexander the Great in 332BC. Painstakingly, he copied in detail the numerous inscriptions he found there. He also visited Shiraz, Babylon, Baghdad, Mosul, and Aleppo. Till he reached southern Europe, he travelled like a man from the Orient—he dressed in their manner, he prepared and ate his meals in their ways, and he slept on a carpet which he always carried with him: reasons he later attributed for his surviving the voyage.

On 20 November 1767, Niebuhr arrived in Copenhagen after a journey that had lasted almost seven years. To Niebuhr’s credit, he saved for posterity the work of his fellow traveller and botanist Forsskål that can be found at Copenhagen’s Botanical Museum and in the Zoological Museum. Baurenfeind’s drawings were released in a book of illustrations that accompanied Forsskål’s zoological and botanical descriptions; his drawings of jellyfish remain the finest of their kind.

After his return, Niebuhr spent nearly 10 years publishing the results. In 1772, his Description of Arabia appeared in print. French and Dutch translations were published in his lifetime, and apparently a condensed English translation came out in Edinburgh (1792). Niebuhr died on 26 April 1815, aged 82. The University of Copenhagen’s Institute for Oriental Studies is named after Carsten Niebuhr.

References

Hansen, Thorkild (2017): Arabia Felix: The Danish Expedition 1761–1767, Trans James McFarlane and Kathleen McFarlane, New York: New York Review Books.

Niebuhr, Carsten (1792): Travels through Arabia, and Other Countries in the East: Volume II, Trans Robert Heron, Edinburgh: R Morison and Son.

- Niebuhr, Carsten. Beschreibung von Arabien. Aus eigenen Beobachtungen und im Lande selbst gesammleten Nachrichten. Copenhagen, 1772.

- Niebuhr, Carsten. Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern. 2 vols. Copenhagen, 1774–1778.

Carsten Niebuhr | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 17 March 1733 |

| Died | 26 April 1815 (aged 82) |

| Nationality | German |

| Occupation(s) | Mathematician, cartographer, and explorer |

| Known for | Danish Arabia expedition (1761-1767) |

Carsten Niebuhr, or Karsten Niebuhr (17 March 1733 Lüdingworth – 26 April 1815 Meldorf, Dithmarschen), was a German mathematician, cartographer, and explorer in the service of Denmark. He is renowned for his participation in the Danish Arabia expedition (1761-1767). He was the father of the Danish-German statesman and historian Barthold Georg Niebuhr, who published an account of his father's life in 1817.

Early life and education

Niebuhr was born in Lüdingworth (now a part of Cuxhaven, Lower Saxony) in what was then Bremen-Verden. His father Barthold Niebuhr (1704-1749) was a successful farmer and owned his own property. Carsten and his sister were educated at home by a local school teacher, then he attended the Latin School in Otterndorf, near Cuxhaven.

Originally Niebuhr had intended to become a surveyor, but in 1757 he went to the Georgia Augusta University of Göttingen, at this time Germany's most progressive institution of higher education. Niebuhr was probably a bright student because in 1760 Johann David Michaelis (1717-1791) recommended him as a participant in the Danish Arabia expedition (1761-1767), mounted by Frederick V of Denmark (1722–1766). For a year and a half before the expedition Niebuhr studied mathematics, cartography and navigational astronomy under Tobias Mayer (1723–1762), one of the premier astronomers of the 18th century, and the author of the Lunar Distance Method for determining longitude. Niebuhr's observations during the Arabia Expedition proved the accuracy and the practicality of this method for use by mariners at sea.

Expeditions

The expedition sailed in January 1761 via Marseilles and Malta to Istanbul and Alexandria. Then the members of the expedition visited Cairo and Sinai, before traversing the Red Sea via Jiddah to Yemen, which was their main destination.

In Mocha, on 25 May 1763, the expedition's philologist, Frederik Christian von Haven, died, and on 11 July 1763, on the way to Sanaʽa, the capital of Yemen, its naturalist Peter Forsskål also died.

In Sanaʽa the remaining members of the expedition had an audience with the Imam of Yemen al-Mahdi Abbas (1719–1775), but suffered from the climate and returned to Mocha. Niebuhr seems to have preserved his own life and restored his health by adopting native dress and eating native food.[1]

From Mocha the expedition continued to Bombay, the expedition's artist Georg Wilhelm Baurenfeind died on the 29th of August and the expedition's servant Lars Berggren on the following day; both were buried at sea. The surgeon Christian C. Kramer (1732–1763) also died, soon after landing in Bombay. Niebuhr was the only surviving member. He stayed in Bombay for fourteen months and then returned home by way of Muscat, Bushire, Shiraz, and Persepolis.[1] His copies of the cuneiform inscriptions at Persepolis proved to be a key turning-point in the decipherment of cuneiform, and the birth of Assyriology.[2][3]

His transcriptions were especially useful to Georg Friedrich Grotefend, who made the first correct decipherments of Old Persian cuneiform:[4]

He also visited the ruins of Babylon (making many important sketches), Baghdad, Mosul, and Aleppo. He seems also to have visited the Behistun Inscription in around 1764. After a visit to Cyprus, he made a tour through Palestine, crossed the Taurus Mountains to Bursa, reached Constantinople in February 1767 and finally arrived in Copenhagen in the following November.[1]

Niebuhr's production during the expedition is indeed impressive. It includes small-scale maps and charts of Yemen, the Red Sea, the Persian Gulf and Oman, and other larger scale maps covering the Nile Delta, the Gulf of Suez and the regions surrounding various port cities he visited, including Mocha and Surat. He completed 28 town plans of significant historical value because of their uniqueness for that period.

In summary, Niebuhr's maps, charts and plans constitute the greatest single addition to the cartography of the region that was produced through field research and published in the 18th century.[7]

Family and later career

In 1773, Niebuhr married Christiane Sophia Blumenberg, the daughter of the crown physician, and for some years he held a post in the Danish military service, which enabled him to remain in Copenhagen. In 1776 he was elected a foreign member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In 1778 he accepted a position in the civil service of Danish Holstein, and went to reside at Meldorf (Ditmarschen).[1] In 1806 he was promoted to Etatsrat, and in 1809 was made a Knight of the Order of the Dannebrog, one of Denmark–Norway's most valued honours for service.

Writing and research

Niebuhr's first book, Beschreibung von Arabien, was published in Copenhagen in 1772, the Danish government providing subsidies for the engraving and printing of its numerous illustrations. This was followed in 1774 and 1778 by the first two volumes of Niebuhr's Reisebeschreibung nach Arabien und andern umliegender Ländern. These works (particularly the one published in 1778), and most specifically the accurate copies of the cuneiform inscriptions found at Persepolis, were to prove to be extremely important to the decipherment of cuneiform writing. Before Niebuhr's publication, cuneiform inscriptions were often thought to be merely decorations and embellishments, and no accurate decipherments or translations had been made up to that point. Niebuhr demonstrated that the three trilingual inscriptions found at Persepolis were in fact three distinct forms of cuneiform writing (which he termed Class I, Class II, and Class III) to be read from left to right. His accurate copies of the trilingual inscriptions gave Orientalists the key to finally crack the cuneiform code, leading to the discovery of Old Persian, Akkadian, and Sumerian.[8]

The third volume of the Reisebeschreibung, also based on materials from the expedition, was not published till 1837, long after Niebuhr's death, under the editorship of his daughter and his assistant, Johan Nicolaus Gloyer. Niebuhr also contributed papers on the interior of Africa, the political and military condition of the Ottoman Empire, and other subjects to a German periodical, the Deutsches Museum. In addition, he edited and published the work of his friend Peter Forsskål, the naturalist on the Arabian expedition, under the titles Descriptiones animalium, Flora Aegyptiaco-Arabica and Icones rerum naturalium (Copenhagen, 1775 and 1776).[1]

French and Dutch translations of Niebuhr's narratives were published during his lifetime, and a condensed English translation of his own three volumes, prepared by Robert Heron, was published in Edinburgh in 1792, under the title "Travels through Arabia". A facsimile edition of this translation, as by "M. Niebuhr", was published in two volumes by the Libraire du Liban, Beirut (undated).

The government funds covered only a fraction of the printing costs for Niebuhr's first book, and probably a similar or smaller proportion of the costs for the other two volumes. To ensure that the volumes were published, Niebuhr had to pay over 80% of the costs himself. In all, Niebuhr devoted ten years of his life, the years 1768–1778, to the publication of six volumes of findings from the expedition. He had virtually no help from the academics who had conceived and shaped the expedition in Göttingen and Copenhagen. It was only Niebuhr's determination to publish the findings of the expedition that ensured that the Danish Arabia expedition would produce results that would benefit the world of scholarship.[7]

Death and legacy

Niebuhr died in Meldorf in 1815.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1749-1832) highly prized Niebuhr's works. In 1811 he wrote to Niebuhr's son, Barthold Georg Niebuhr, that "You carry a name which I have learned to honour since my youth."

Carsten Niebuhrs Gade, a street in the port area of Copenhagen, is named for him.

In 2011, Copenhagen's National Library and National Museum held exhibitions of Carsten Niebuhr's life and work, celebrating the 250th anniversary of the Danish Arabia Expedition's commencement. Commemorative Carsten Niebuhr postal stamps were issued. And in the same year the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs had planned a series of cultural events based on the Expedition and Niebuhr's work that would take place in Ankara, Cairo, Damascus, Beirut, Tehran, and Yemen. It has been suggested that these efforts were intended in part to repair the reputational damage in the Islamic world caused by the Danish cartoon controversy. Ultimately, the planned events were prevented by the Arab Spring.[9]

![Niebuhr inscription 1. Now known to mean "Darius the Great King, King of Kings, King of countries, son of Hystaspes, an Achaemenian, who built this Palace".[4] Today known as DPa, from the Palace of Darius in Persepolis, above figures of the king and attendants [5]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/51/Niebuhr_inscription_1.jpg/350px-Niebuhr_inscription_1.jpg)

![Niebuhr inscription 2. Now known to mean "Xerxes the Great King, King of Kings, son of Darius the King, an Achaemenian".[4] Today known as XPe, the text of fourteen inscriptions in three languages (Old Persian, Elamite, Babylonian) from the Palace of Xerxes in Persepolis.[6]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4a/Niebuhr_inscription_2.jpg/350px-Niebuhr_inscription_2.jpg)