How Muslim ghettos came about in Delhi

From 'Muslim Zones' needing protection from violence in 1947 to 'unhygienic pockets requiring beautification' in 1970s to "terrorist hide-outs" post 2000s.

Written by Atikh Rashid

|

Updated: March 3, 2020 8:50:28 pm

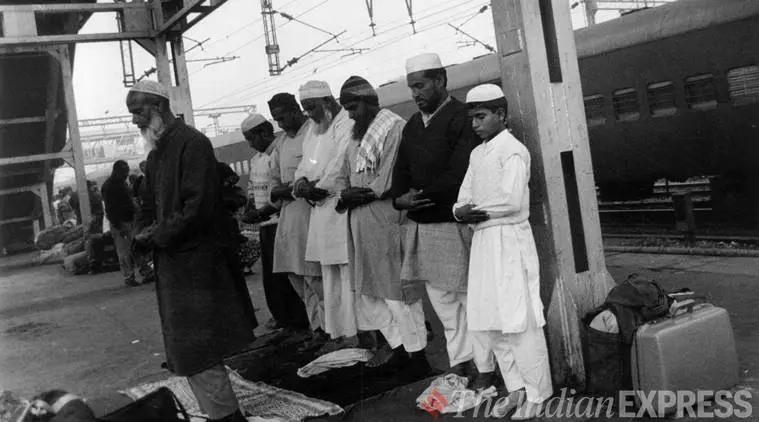

Muslims offering prayer at the Hazrat Nizamuddin Station in New Delhi. (Express archive photo by Vasant Prabhu)

Partition and the resultant influx and efflux of communities caused a

sea change in the demography and character of the Delhi city.

Muslims offering prayer at the Hazrat Nizamuddin Station in New Delhi. (Express archive photo by Vasant Prabhu)

Partition and the resultant influx and efflux of communities caused a

sea change in the demography and character of the Delhi city.Before partition, the city was home to a big and prosperous Muslim community which comprised of about one-third of the city’s population. However, the emigration of Muslims – some out of choice, others due to compulsion of violence – reduced the Muslim population of Delhi drastically. It is estimated that around 3.3 lakh Muslim residents of Delhi left for Pakistan and around 5 lakh Hindu and Sikh refugees from riot-torn West Punjab came to Delhi.

As per estimates, the Muslim population of Delhi came down from 33.33 per cent in 1941 to a mere 5.33 per cent in 1951.

Several localities which were predominantly Muslim, such as Chandani Chowk, Khari Baoli and Karol Bagh were emptied out to a great extent with the emigration of Muslims and were replaced with Punjabi Hindus and Sikhs.

Creation of ‘Muslim Zones’

In the aftermath of Partition, Delhi was thrown into grips of anti-Muslim violence, especially at the hands of Hindu, Sikh refugees coming from West Pakistan who had suffered the loss of life and property. Between August-October 1947, as many as 20,000 Muslims were killed within Delhi in communal riots and almost all the Muslim residents – especially from mixed localities – had shifted to temporary camps that had sprung up in Purana Qila, Nizamuddin and Humanyun’s Tomb.When tempers calmed – with efforts by Mahatma Gandhi and Maulana Azad – the Muslims in the camps who had not migrated to Pakistan started returning to their homes. It was felt by the government that ‘mixed areas’ – where Muslims and Hindus previously stayed together – were no longer safe for Muslims to return to. The government decided to rehabilitate displaced Muslims in predominantly Muslim localities such as Pul Bangash, Phatak Habash Khan, and Sadar Bazar and Pahari Imli’ areas which in government communications were being referred to as ‘Muslim Zones’. It can’t be ascertained to what degree the government succeeded in implementing this plan fully, but it was put in motion by the agencies surely.

“Certain largely Muslim mohallas were cordoned off, and abandoned houses there were to be kept empty by police intervention so that either Muslims could return to them or other Muslims could be moved there and provided safety,” says Vazira Zamindar her book The Long Partition and The Making of Modern South Asia.

Zamindar quotes Sardar Diwan Singh, the editor of Risalat’s account of how this shifting from ‘mixed localities’ to ‘Muslim zones’ happened.

“Muslims from mixed areas were asked to move to the Muslim zones. The constable stood at the street corner and they had five minutes to gather their belongings and go. Many thought this was only a matter of a few days and that they would return when the public had calmed down…”.

But, as per Singh, the Muslims did not or could not return to the houses.

Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru supported this policy saying if Hindus and Sikhs were accommodated in empty houses left behind by Muslims who departed for Pakistan, it would “push out” Muslims residents.

“There was a tendency on the part of the Muslim residents of the other houses, next door, to leave their houses because they felt they were being pushed out,” he said later in a parliamentary debate.

The Muslim Zones thus created soon were attached with a stigma of being “communally sensitive areas” and “zones of trouble”.

“For Muslims staying in these ilaqe (areas) was not a matter of choice; nor was these enclaves celebrated zones of culture. Instead, living in these areas became a compulsion for Muslims for safety. In a span of a few years these pockets were marked as ‘communally sensitive area(s)’- a stigma that transformed these areas in later decades from protected sites into alleged zones of trouble,” writes Nazma Parveen in her study on ‘Muslim localities of Delhi’.

Resettlements of Shahjahanabad

About three decades letter, another round of creation of Muslim ghettos happened. It was due to the ‘urban beautification-inspired demolition drives’ that were held in the midst of Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi. The drives, executed by Jagmohan Malhotra of Delhi Development Authority (DDA), were aimed at beautification of Jama Masjid, Turkman gate areas with a plan to revamp Shahjahanabad. Thousands of residents of these areas (mainly Muslims) were forcefully and violently evicted and ‘resettled’ in localities such as Seelampur and Welcome.As per author Ghazala Jamil, these areas continued to expand during 1980s as more Muslims from the Old Delhi areas who shifted out from Old Delhi houses due to various reason started settling in and around Seelampur and Welcome. Hindus moving out of Old Delhi would, on the other hand, shift to Shahadara, Geeta Colony and Uttam Nagar. Also, in localities where Muslim-population was greater, Hindus sold off their properties and moved out and these localities became largely Muslim.

“By the late 1980s, segregation in Delhi on religious identity lines became almost final and complete,” Jamil writes in Accumulation by Segregation: Muslim Localities in Delhi.

Migration of UP, Bihar and elsewhere

From the 1990s, Muslim migrants from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and other areas of north India started coming and settling in the localities north of Seelampur and formed the belt of largely Muslim localities in ‘trans-Yamuna’ areas ranging between Seelampur and Loni Border including Gautampuri, Chandbagh, Jafferabad, Gokulpuri and other areas where the recent Delhi riots were largely concentrated.During the same period, Jamia Nagar saw unprecedented expansion with migration of aspirational migrants from north India and many new colonies came up. Some scholars have linked the migration of 1990s and 2000s of Muslims from UP and Bihar to Delhi’s Muslim ghettos to communal polarisation that happened during Ram Janmabhoomi Movement and 2002 riots of Gujarat.

“A very small portion of this population (residing in newer ghettos) can trace their earlier generation residing in Delhi before 1947, a vast majority being migrants from UP and Bihar. The pockets of Muslim population got consolidated (some even expanded) after each communal riot in the country especially the post-Babri Masjid demolition riots in 1992 and Gujarat pogrom in 2002,” writes Jamil.

The affluent class among Muslims who did not identify with the lot living in the ghettos formed gated enclaves either within these Muslim areas or on the borders in localities like Zakir Nagar Extension, Joga Bai Extension, Joharmi Farms or housing societies like the Taj Enclave.

“Still shunned from the affluent Hindu areas they resorted to using a new group membership as a source of positive self-esteem,” observes Jamil.

‘Terror Hide-Outs’ requiring combing operations

In one of his report (June 1 1948) about the plan of ‘Muslim Zones’, Delhi’s then Deputy Commissioner M S Randhawa refers to these zones as ‘Miniature Pakistans’ creation of which is being resented by Hindu and Sikh refugees of Delhi.In over seven decades since, the Muslim ghettos of Delhi – as those elsewhere in India – have not been able to shake off the stigma, suspicion and derision associated with them. Researcher Nazima Parveen writes about their journey in the following manner:

“These localities were looked at differently over the period. In the 1940s they were seen as ‘Muslim-dominated’ areas that were to be administered for the sake of communal peace, in the 1950s, as ‘Muslim zones’ that needed to be ‘protected’, in the 1960s, as ‘isolated’ unhygienic cultural pockets that were to be cleaned and Indianized, and in the 1970s as location of ‘internal threat’ – the Mini-Pakistans – that were to be dismantled and integrated. In altered political scenarios of 1990s and 2000s these pockets were looked at as ‘terrorist hide-outs,” writes Parveen.

📣 The Indian Express