Bellevue Operating Room, Late 19th Century

- Image ID: HRKPFEThe history and value of face masks

Associated Data

Abstract

In the human population, social contacts are a key for transmission of bacteria and viruses. The use of face masks seems to be critical to prevent the transmission of SARS-CoV-2 for the period, in which therapeutic interventions are lacking. In this review, we describe the history of masks from the middle age to modern times.

Background

In last few months, many communications were brought to the public that face masks are ineffective during a pandemic crisis. Since April 27, 2020 face masks have become mandatory for shopping and in public transportation in Germany. In the Netherlands, it became mandatory only for public transportation, from June 1, 2020 onwards. However, in Asian countries people have been wearing masks in public for ages. Although New York and Hong Kong are both metropolitan areas, the corona virus pandemia was devastating in the US and not in Hongkong. This fact alone implies a necessary, and a more distinguished view of the normative application of facemasks. In two manuscripts, we are now describing the use of masks during this viral pandemic. This first review describes the history of facemasks. The second will concentrate on benefits and risks by wearing facemasks in modern times.

Review

“The surgical face mask has become a symbol of our times” [1]

On March 17, 2020, this headline appeared in the New York Times on an article regarding the role of face masks in times of the COVID-19 outbreak. This is the most recent expression of the use of face masks. However, face masks have been used since the middle ages.

Middle ages to renaissance

There are pictures of medical professionals from the early modern age treating patients suffering from the bubonic plague wearing beak-like masks. These masks were supposedly filled with herbs such as clove or cinnamon as well as liquids and led to the term ‘beak-doctors’ [2] (Fig. 1). The doctors were dressed in black cloaks and dark hats and were considered the symbol of the deathly epidemic of the Middle Ages. Their masks were meant to protect from the ‘blight’, the miasma, which was considered the cause of the plague back then. It was proclaimed that spoiled air from the East had caused the epidemic. Nevertheless, there is no proof that these ‘plague-doctors with beak-like masks’ really existed. There are two masks displayed in German museums that are suspected to be forgeries from a younger date. That indicates that the beak-doctors were in retrospect awarded a meaning they apparently did not have in reality [3].

Colored version of a copper engraving of Doctor Schnabel (i.e., Dr. Beak), a plague doctor in seventeenth-century Rome, circa 1656 by Paul Fürst (1608–1666) of Nuremberg made for a broadsheet, German derivate of a sheet of Sebastiano Zecchini, 1656

(source Wikipedia https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Pestdoktor#/media/Datei:Paul_Fürst,_Der_Doctor_Schnabel_von_Rom_(coloured_version).png)

1800–1900

Heroic stories of the introduction of antisepsis by Joseph Lister (1827–1912) and the corresponding preliminary works by Louis Pasteur (1822–1895) or Ignaz Semmelweis (1818–1865) [4] have inspired movie productions for decades and had an impact on our culture of remembrance. In contrast, the bacteriologic era that influenced the development of surgery has only recently been analyzed for the German area by Schlich et al. [5]. Ever since the works of Lister and Pasteur, the surgical ward and its developing special disciplines were confronted with a trend-setting discourse about wound infections and their prohibition and containment. This began in 1870, as the ‘hospital gangrene’ was limiting the outcomes of operations, especially those concerning abdominal procedures and those involving bones.

The introduction of mouth and nose coverage (mouth protection, face veils, face masks, mouth bandages) can be followed back to the turn-of-the-20th-century.

In 1897, the hygienist Carl Friedrich Flügge (1847–1923) working in Breslau at this time published his works on the development of droplet infections [6–8] as part of his research on the genesis of tuberculosis [7]. At that time, the respiratory system as a transmitter of germs came into focus of research and already mandated instructions to keep distance [7, 9]. In the same year, 1897, a cooperation work between Flügge and Theodor Billroth’s (1829–1894) disciple Johannes von Mikulicz (1850–1905), who also worked in Breslau since 1890, was published. Their publication dealt with performing operations wearing a ‘mouth bandage’. In here, Mikulicz described a one-layered mask made of gauze [10].

Mikulicz, who had already been responsible for the introduction of sterile gloves made from cloth, noted concerning the applicability of surgical masks: ‘…we breathed through it as easily as a lady wearing a veil in the streets…’

Mikulicz’ assistant Hübner resumed the topic and described a two-layered mouth protection made of gauze that should prevent driblet spread. More studies regarding the germ content in the operating room air followed [11, 12].

Until 1910, the application of face covers was not common in surgery and the general hospitals. Nevertheless, an earlier illustration of a multilayer face mask made of gauze can be found in the surgical operating teachings of the British surgeon B.G.A. Moynihan (1865–1936) (Fig. 2).

Modern area

In 1914, the surgeon Fritz König (1866–1952) noted in a handbook on surgery for general practitioners:

“…Due to our experience of many years we consider their (mouth masks) - by the way quite irritating – use altogether unnecessary. Only those afflicted with a catarrh or angina should wear a mouth bandage when operating that is to be sterilised in steam. Speaking should be limited and the direction of the operative field avoided…” [13]

The surgical mask was used first in the operating rooms of Germany and the USA in the 1920s. Especially in endoscopic procedures or ‘small surgery’, the mask was renounced for a long time. There was still no hint for a facemask in the book ‘assistance for operating staff’, that was widely read in German-speaking areas in 1926, while the processing of cystoscopies for instance, also taking place in the clinical use around 1900, was described extensively on several pages [14, 15]. One year later, Martin Kirschner (1879–1942), who held the chair for surgery in Heidelberg, elaborately described the necessity of wearing a facemask in his multi-volume operational theory in the chapter ‘measures to combat infections’ [16]. In the following edition of the book ‘assistance for operating staff’ published in 1935, facemasks were then mentioned [17], which can probably be related to the increased number of studies on the reduction of germs [18, 19].

A similar situation applies for the United States. In that country, following the First World War, more and more research addressed facemasks with varying thickness [20–23]. Still, masks were not generally accepted, which can be seen in contemporary photographs [24] or paintings (Figs. 3, ,44 and and5).5). While interns and nurses were already wearing facemasks made of cloth or gauze, the generation of head physicians rejected them, as well as rubber gloves, in all phases of an operation, as they were considered “irritating”.

Hermann Otto Hoyer (1894–1968) 1922 Sauerbruch in a thoracotomy, Museum of Medical History at the Charité, art collection Charité, picture Bruns Inv.-Nr. 123330 Repro Moll-Keyn, with kind permission

‘Our introduced face mask and forehead bandage’ and ‘face mask for person with long hair’ from: Kirschner, M. Allgemeine und Spezielle Chirurgische Operationslehre Bd 1, Julius Springer, Berlin, 1927 S. 222, Repro Moll- Keyn, with kind permission. At this time, it was not common covering the nose with the cloth-made mask

Dr. med. Ewald Matuschek and his team

(source: PD Dr. med. Christiane Matuschek, daughter of Dr. med. Ewald Matuschek)

In the middle of the 1930s, the research on the role of facemasks was continued in Germany and the USA [25, 26]. Only in the 1940s, washable and sterilizable masks gained acceptance in German and international surgery with only the number of gauze layers varying (2–3, 3–4) [27, 28].

Beginning in the mid-1960s, the use of disposable items made of paper and fleece was introduced all over the world after this was started in the USA.

Still in the 1990s, there were only uncertain data available. Therefore, an unresolved discussion was present between surgery and hospital hygiene, if wound infections could be reduced by the use of surgical mouth and nose protection [29, 30]. Today, following the recommendations of the RKI (German Robert Koch-Institute for hygiene), the available data indicate that surgical facemasks lower the contamination of indoor air [31].

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the use of facemasks seems to be an accepted procedure worldwide although a scientific discussion is going on up to now, which has its roots in the history of medicine and science. Future research on efficiency and efficacy of long-term mask wearing outside of hospital settings is warranted and will allow for insights that are more detailed.

Abbreviations

...............................................................

Nation of shopkeepers

The phrase "a nation of shopkeepers", commonly attributed to Napoleon, is a reference to England or the United Kingdom.

There is reason to doubt that Napoleon ever used it. No contemporaneous French newspaper mentions that he did. The phrase was first used in an offensive sense by the French revolutionary Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac on 11 June 1794 in a speech to the National Convention: “Let Pitt then boast of his victory to his nation of shopkeepers”.[1] Later, during the Napoleonic wars, the British press mentioned the phrase, attributing it either to “the French” or to Napoleon himself.[2]

A later, explicit source is Barry Edward O'Meara, who was surgeon to Napoleon during his exile in St. Helena.[3] If O'Meara is to be believed, Napoleon said:

Your meddling in continental affairs, and trying to make yourselves a great military power, instead of attending to the sea and commerce, will yet be your ruin as a nation. You were greatly offended with me for having called you a nation of shopkeepers. Had I meant by this, that you were a nation of cowards, you would have had reason to be displeased; even though it were ridiculous and contrary to historical facts; but no such thing was ever intended. I meant that you were a nation of merchants, and that all your great riches, and your grand resources arose from commerce, which is true. What else constitutes the riches of England. It is not extent of territory, or a numerous population. It is not mines of gold, silver, or diamonds. Moreover, no man of sense ought to be ashamed of being called a shopkeeper. But your prince and your ministers appear to wish to change altogether l'esprit of the English, and to render you another nation; to make you ashamed of your shops and your trade, which have made you what you are, and to sigh after nobility, titles and crosses; in fact to assimilate you with the French... You are all nobility now, instead of the plain old Englishmen.

There may be grounds to doubt the veracity of this account.[4]

The supposed French original as uttered by Napoleon (une nation de boutiquiers) is frequently cited, but it has no attestation. O'Meara conversed with Napoleon in Italian, not French. There is no other source.

After the war English newspapers sometimes tried to correct the impression. For example the following article appeared in the Morning Post of 28 May 1832:[5]

ENGLAND A NATION OF SHOPKEEPERS This complimentary term, for so we must consider it, as applied to a Nation which has derived its principal prosperity from its commercial greatness, has been erroneously attributed, from time to time, to all the leading Revolutionists of France. To our astonishment we now find it applied exclusively to BONAPARTE. Than this nothing can be further from the fact. NAPOLEON was scarcely known at the time, he being merely an Officer of inferior rank, totally unconnected with politics. The occasion on which that splenetic, but at the same time, complimentary observation was made was that of the ever-memorable battle of the 1st of June. The oration delivered on that occasion was by M. BARRERE [sic], in which, after describing our beautiful country as one "on which the sun scarce designs to shed its light", he described England as a nation of shopkeepers.

In any case the phrase did not originate with Napoleon, or even Barère. It first appears in a non-pejorative sense in The Wealth of Nations (1776) by Adam Smith, who wrote:

"To found a great empire for the sole purpose of raising up a people of customers may at first sight appear a project fit only for a nation of shopkeepers. It is, however, a project altogether unfit for a nation of shopkeepers; but extremely fit for a nation whose government is influenced by shopkeepers."

— Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations[6]

Smith is also quoted as saying that Britain was "a nation that is governed by shopkeepers", which is how he put it in the first (1776) edition. It is unlikely that either Adam Smith or Napoleon used the phrase to describe that class of small retailers who would not even have had the franchise.

The phrase may have been part of standard 18th-century economic dialogue. It has been suggested that Napoleon may have heard it during a meeting of the French Convention on 11 June 1794, when Bertrand Barère de Vieuzac quoted Smith's phrase.[7] But this presupposes that Napoleon himself, as opposed to Barère alone, used the phrase.

The phrase has also been attributed to Samuel Adams, but this is disputed; Josiah Tucker, Dean of Gloucester, produced a slightly different phrase in 1766:

And what is true of a shopkeeper is true of a shopkeeping nation.

Napoleon would have been correct in seeing the United Kingdom as essentially a commercial and naval rather than a land based power, but during his lifetime it was fast being transformed from a mercantile to an industrial nation, a process which laid the basis for a century of British hegemony after the Battle of Waterloo. Although the UK had half the population of France during the Napoleonic Wars, there was a higher per capita income and, consequently, a greater tax base[citation needed], necessary to conduct a prolonged war of attrition. The United Kingdom's economy and its ability to finance the war against Napoleon also benefitted from the Bank of England's issuance of inconvertible banknotes, a "temporary" measure which remained from the 1790s until 1821.[8]

POST SCRIPT:-

THEY MADE MONEY BY LOOTING INDIA

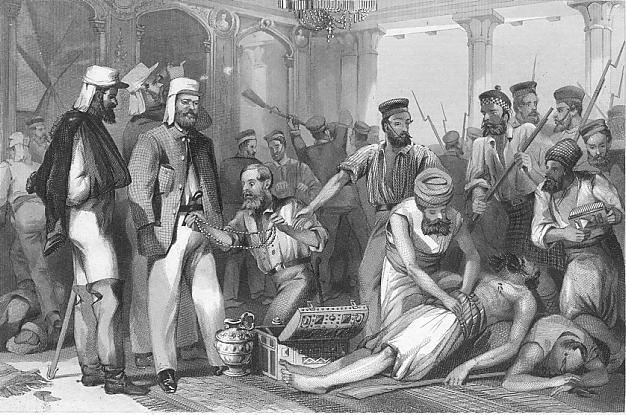

File:British soldiers looting Qaisar Bagh Lucknow.jpg ...

File:British soldiers looting Qaisar Bagh Lucknow.jpg

British_soldiers_looting_Qaisar_Bagh_Lucknow.jpg (626 × 415 pixels, file size: 75 KB, MIME type: image/jpeg)

Summary

| Description | British soldiers looting Qaisar Bagh, Lucknow, after its recapture (steel engraving, late 1850's). The steel engraving depicts the Time correspondent looking on at the sacking of the Kaiser Bagh, after the capture of Lucknow on March 15, 1858. "Is this string of little white stones (pearls) worth anything, Gentlemen?" asks the plunderer. |

| Date | |

| Source |

|

| Author | Unknown author |

| Permission (Reusing this file) |

Public domain |

The Red Fort was of course looted too , and parts of it were heavily damaged as well (Illustrated London News, 1858): very large scans of *the upper picture* and *the lower picture*

Source: ebay, Mar. 2010

"The Plunder of the Kaiserbagh," William Howard Russell, 'My Diary in India', vol. 1, 1860-BRITISH SOLDIER IN RED JACKET

1 and

1 and