Why photographer Chirodeep Chaudhuri is fascinated by Mumbai’s public clocks

A clock shaped like a man with a turban and one featuring only Hindi letters are some of the unusual clocks Chaudhuri has captured

Public clocks have caught photographer Chirodeep Chaudhuri’s eye for a while now. During his research in Mumbai, about 15 years ago, he came across an old home in Vile Parle, crowned by an old German clock. The owners had a shop at Abdul Rehman Street that sold time pieces. In the 1950s, the clock had been installed by men flown in from Germany. Since then, the weekly ritual at Bhagat Bhuvan was for the head of the family, Janak Bhagat, to wind the clock on Sunday morning. The clock ran for about a week, before the process was repeated.

Similar stories of how a city in a hurry finds the time for its public clocks are a part of Chaudhuri’s exhibition, “Seeing Time: Public Clocks of Bombay”, on at Max Mueller Bhavan in Mumbai till February 20.

Eighty-one public clocks in Mumbai, old and new, that Chaudhuri, 47, discovered simply by walking around in the city or through tip-offs from friends, make their way into the show. In one frame from 2016, Chaudhuri zooms in on the shop, Shridhar Bhalchandra and Co., established in 1917, that sold the Maharashtrian nauvari saris in Girgaon. Its shutters are down and a clock rests in between its nameplate. The day Chaudhuri spoke to the owner of the store turned out to be its last day. “What’s unusual about the clock is that there are no numbers, and it is made up entirely of Hindi alphabets that make up their shop’s name,” says Chaudhuri. When the clock stopped working , passersby and neighbours would go to the sari shop, inform the staff and ask them to get it fixed. “So people did engage with this technology. In earlier times, people negotiated the city by foot, unlike today where many people are driving around and being driven. When you are walking around the city, the chances of spotting the clocks are much more. A lot of them are now defunct because that necessity has worn off, a lot more of us are looking at wrist watches or our mobile phones,” he says.

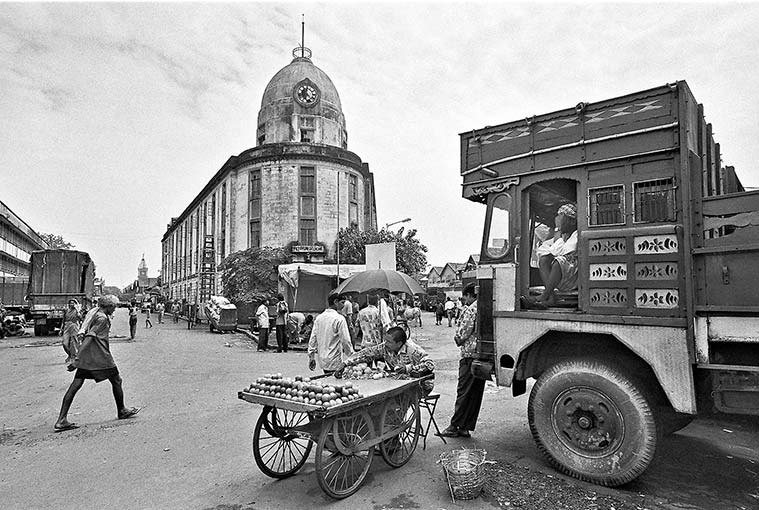

Eighty-one public clocks in Mumbai, old and new, that Chirodeep

Chaudhuri, 47, discovered simply by walking around in the city or

through tip-offs from friends, make their way into the show. (Photo:

Abhijit Bhatlekar)

Eighty-one public clocks in Mumbai, old and new, that Chirodeep

Chaudhuri, 47, discovered simply by walking around in the city or

through tip-offs from friends, make their way into the show. (Photo:

Abhijit Bhatlekar)

The idea to explore this rather unusual subject came to Chaudhuri in Kolkata. He was in Esplanade, when he spotted a humungous clock on top of the Metropolitan Building. “That was the moment when I became conscious of public clocks,” he says. He began his first job as a photographer in Mumbai at the Sunday Observer. From 1996, between assignments, he began to photograph the clocks. Delhi-born Chaudhuri has worked as a journalist for the last 25 years for a variety of newspapers and magazines such as the National Geographic Traveler and TimeOut, and documented Mumbai extensively.

In these years, Chaudhuri has seen many of the clocks disappear. A clock shaped like a man with a turban adorns the Hallai Mahajan Bhatiawadi Chawl on Kalbadevi Road in a 2009 photograph. “There was a fire in that chawl in November last year and that clock got burnt,” says Chaudhuri. The Indian Sailors Home at Masjid Bunder from 1997 had a clock on its dome, which has now been replaced by glass panes. “That one was sent for repair and no one bothered when it did not return,” he says.

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus

Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus

Chaudhuri first exhibited 20-odd pictures at the Kala Ghoda festival in Mumbai in 1999. He says, “That exhibition went on to become hugely popular. It drew out people from their homes. Four ladies, all housewives, landed up to test me and find out if they had found any clocks that I didn’t know about. That kept me going for some more years, knowing people were excited by this subject,” he says. That exhibition has now enlarged into a display of 81 photographs of clocks.

The biggest task for Chaudhuri in his two-decade long project has been to convince people to let him into their homes to photograph the spaces from their terraces and balconies. “I think in today’s times, where there is so much of suspicion and depleting trust, the fact that I could go and approach people, in what would be completely cold calls, and ask them to let me use their balcony or kitchen window was special. A lot of pictures wouldn’t have happened without their cooperation,” he says.

Sridhar Bhalchandra & Co., Prarthana Samaj

Sridhar Bhalchandra & Co., Prarthana Samaj

Chaudhuri points out that many clocks tend to be located near places of worship, be it a mosque, temple or church, given how time played an important role in rituals. It’s no surprise then to spot Christ Church at Clare Road, Rasool Masjid on Shaikh Burhan Kamruddin St and Dwarkadhish Temple on Kalbadevi Road in Chaudhuri’s latest collection. A Muslim would refer to the clock for namaaz five times a day, those heading for the Sunday mass could catch a glimpse of it on their way to the church. The buildings served as landmarks in a neighbourhood. “This is how citizens negotiated the city and the buildings became important,” he says.

The oldest clock in his collection of images goes back to the 16th century — a Portuguese-era sundial in the middle of the Naval Dockyard, which most citizens will not get to see it since it comes under the security zone. There are also some clocks from the Art Deco phase of the 1930s and 1940s, though it is a misconception, says Chaudhuri, that most were made by the British.

Indian Sailors Home, Masjid Bunder

Indian Sailors Home, Masjid Bunder

Clocks continue to be installed in housing localities even now, such as at the L&T Emerald Isle in Powai two years ago. But most of the public clocks are not working, which Chaudhuri blames on apathy. “A large chunk of these clocks are from the British period. Since a lot of the factories have shut down and there are no spare parts available. Then, there is the obvious issue of finances to restore them. If one has to get these restored, it is not just about placing two parts. It is an elaborate exercise — the building has to be restored and the clock mechanism too,” he says.

When doing a bunch of interviews in the city to know how its people connected with clocks, he came across varied opinions. Chaudhuri says, “When I was speaking to the students at St Xavier’s College, they didn’t know about the clock even when standing at the quadrangle with the clock right behind them. They never noticed. People from the older generation told me about this particular building in Mahim. As kids, they would look at the clock on their way to school, but have now lost the habit because, 40 years ago, the clock stopped.”