Narco-colonialism: How Britain exploited Indians for its drug trade with China

India Independence Day 2025: A century-long British colonial opium trade in India exploited millions of farmers, becoming the regime's second-largest income source. Farmers were coerced into cultivating opium, sold at fixed prices that barely covered costs, trapping them in debt.

iStock

iStockRecent research sheds light on the disturbing mechanics of how millions of Indian peasants were systematically trapped in a cycle of poverty to support Britain’s imperial trade interests. This wasn’t merely about cultivating a cash crop -- it was about using state power to turn entire agrarian economies into instruments of global drug trafficking.

Also Read: Before Trump, British used tariffs to kill Indian textile

From colonial trade to narcotic empire

By the late 18th century, the British East India Company had transformed from a trading corporation into a de facto colonial government in India. Among its many revenue-generating ventures, opium soon emerged as one of the most profitable. However, its profitability wasn’t rooted in market competition or innovation. It was built on a monopoly of force, debt and agricultural coercion.

The company had two key goals: extract wealth from India, and break into the lucrative Chinese market. Britain’s appetite for Chinese tea, porcelain, and silk far outstripped its ability to offer goods the Chinese wanted in return. So the British turned to opium, a narcotic substance outlawed in China but increasingly in demand. India, with its fertile Gangetic plains and impoverished peasantry, became the perfect site for mass opium production.

Also Read: When Made-in-India engines alarmed the British

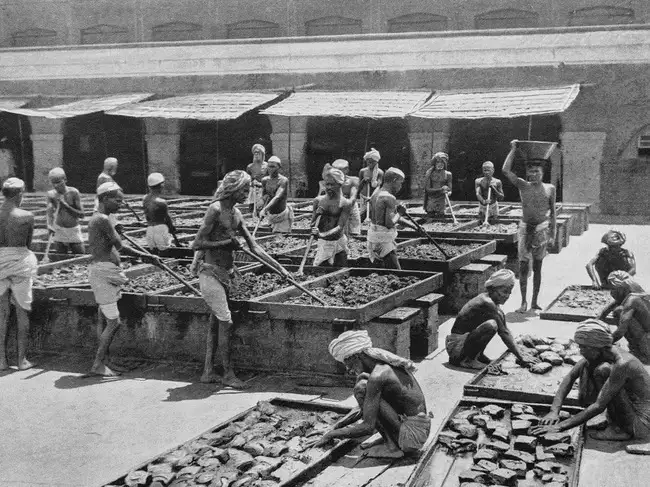

The raw opium harvested in India was processed in government factories and shipped to China, where it was smuggled in and sold through a growing network of British and Indian merchants. Despite Chinese imperial attempts to ban the drug, its addictive properties ensured a massive, ever-expanding consumer base.

When the Qing dynasty cracked down on the trade in the 1830s, Britain responded not with diplomacy but with gunboats. The First Opium War (1839–42) forced China to legalise the trade and open key ports to British merchants. What began as economic manipulation in India ended in military aggression in China. The entire apparatus -- cultivation in India, smuggling into China, profits returning to London -- was the backbone of the narcotic empire.

The opium monopoly and state-enforced cultivation

Bauer’s work shows that opium production in colonial India was not simply a case of supply meeting demand. It was a state-organised, top-down economy where farmers were compelled to grow a crop they neither needed nor profited from. In regions like Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh, entire farming communities were bound into long-term relationships with British opium agencies.

Every year, farmers were given loans to grow opium poppy on a certain portion of their land. These advances were not optional. Officials used a combination of bureaucratic pressure, coercion and threats to ensure compliance. Once the crop was harvested, it had to be sold only to the government, at fixed prices which rarely covered even the basic costs of cultivation.

According to Bauer, British authorities kept the purchase price of raw opium low and stable, regardless of inflation or fluctuations in input costs like irrigation, labour or manure. This ensured that the colonial state’s profits were maximised but it also guaranteed that peasants remained trapped in a cycle of loss. Since their earnings never covered their debt, they were forced to take more loans the following season, securing their continued involvement in the trade.

"Even if we take the highest possible gross income and the lowest possible costs of poppy cultivation, we must conclude that the peasants produced opium at a loss," Bauer writes.

Also Read: After Jhansi ki Rani, another queen fought the British

Opium as economic extraction

What Bauer highlights is the structural nature of this exploitation. Indian farmers did not simply make bad decisions or grow an unprofitable crop out of ignorance. The entire system was designed to extract labour and value from them while offering no exit. The opium trade operated like a colonial drug cartel with the added power of a state apparatus. Tax collectors, police and civil officials all worked together to maintain the supply chain.

Bauer's book refers to documented incidents in which peasants were kidnapped, harassed with the destruction of their crops or threatened with criminal prosecution and imprisonment if they refused to cultivate poppy. "The opium laws equipped the Department’s agents with an executive power that enabled them to break open doors, search houses and arrest people. While these laws were primarily passed to protect the monopoly and prevent the illegal sale of opium, they also formed the legal basis of a highly coercive system," he writes.

Moreover, the cultivation of opium displaced food crops. As more land was diverted to poppy fields, rural food security declined. This was particularly disastrous in times of drought or crop failure. The colonial state's insistence on non-negotiable production quotas left little room for local food autonomy or resilience. Hunger and indebtedness went hand in hand.

The human cost of imperial profit

The opium trade was never a market in the sense of free exchange between equal participants. It was a coercive system that used state power to generate addiction abroad and destitution at home.

What’s particularly damning is that this system persisted for over a century, even as colonial administrators and British politicians knew full well the social devastation it caused. Opium revenues became essential to funding the colonial state and balancing British trade deficits. Morality was subordinated to fiscal necessity.

The story of the British opium trade cannot be told solely through the lens of diplomacy or international trade. It must be understood as a structure of systemic exploitation rooted in the coercive apparatus of empire. Bauer’s scholarship refocuses attention on the Indian farmers, those who bore the burden of imperial ambition, and whose suffering financed both colonial administration and global expansion. As historians continue to reassess the legacies of colonialism, the opium trade stands as a grim reminder of how deeply economic violence was embedded in imperial enterprise.