Girgaum road

Until the second half of the 19th

Century, Girgaum remained characterized by a large concentration of

gardens and palm groves; however, significant changes started emerging

in Bombay due to the development of trade and communications channels.

The first dock was built in 1736, and port developments kept occurring until 1914. By the beginning of the 19th

Century, the population of the city had reached 120 000 inhabitants.

Other factors contributed to speeding up Bombay’s development as well.

In 1813, the East Indian Company lost its exclusive control of trade, as

rival companies established themselves and flourished. Steamboats and

railways in the late nineteenth century further accelerated the growth

of the city, rendering the older large Portuguese landholdings and

organizations economically unsustainable. The East India Company thus

divided lands to make them accessible to individual farmers, who

subsequently became landowners.

It is in such a context that Dadoba Waman

Khot – a Pathare Prabhu, a sub-caste of the region’s Brahmin community –

received lands in Girgaum. Initially collecting revenues from Hindu

farmers only, he progressively extended his collection to the East

Indian Christian community that he helped to settle. In practice, the

community began investing in this space around 1840. By 1880, the

locality had officially adopted the name of Khotachiwadi, acknowledging

the significant role played by the Khot family in its development.

Khotachiwadi’s growth is unquestionably

linked to the widening of roads. In 1839, Parel and Breach Candy Roads

(later renamed Girgaum Road and Jagannath Shankarsheth Road

respectively) gained 60 feet in width, while Grant Road was opened to

traffic, thus facilitating greater access to the area.

In the 19th Century, a new

wave of Christian populations coming from Goa – where the Portuguese

Empire still kept its influence – migrated to Bombay. These Goan

Christians, also called Portuguese Christians, were Portuguese subjects,

contrarily to local Christians who were subjects of the British crown.

Feeling threatened by this new influx

which the local Christians of Bombay feared would undermine their status

and privileges, they formulated a request in 1832 asking to be

recognized as East Indian Christians, marking their Indo-British

affiliation more pronounced. At the same time, this move helped

distinguish them from the Koli fishermen Hindu populations as well.

In 1887, during Queen Victoria’s « Golden

Jubilee Year », the community’s leaders filed a petition to officially

use the name “East Indian Christians” as a means to establish their

administrative and official rights and privileges as original

inhabitants of Bombay.

At the same time, in several localities,

such as Mazagaon, Bandra and Girgaum, the Christian communities had

grouped and started to live together, Goan and East Indian alike. To

this day, Khotachiwadi continues to epitomize this trend. Today, even if

members of the two communities still distinguish each other, the

official census does not recognize the distinction. According to a

survey done on Khotachiwadi in the 1990s by the Mumbai Metropolitan

Regional Development Authority (MMRDA), the two communities have merged,

following their common religious affiliation. Thus Khotachiwadi’s

“Christians” represent 44% of the population, “Maharastrians” 36% and

“Gujaratis” 16%. Far from generating tensions, the diversity of

Khotachiwadi is a source of pride for its inhabitants. They valorize the

neighborhood’s special nature by presenting it as a place of openness

and exchange, a place with an inspiring past and a promising future.

News › Culture News

News › Culture News

9 hours ago - A new book, Bomoicar (Konkani for 'Bombaywallah'), chronicles the life and times of Goans in Mumbai, through various voices. An extract.

Waves

of nostalgia: The Konkan Shakti, one of two passenger steamers operated

by Chowgule-owned Mogul Line - See more at:

http://www.mid-day.com/articles/stories-of-mumbais-goans/15360197#sthash.lWE8s68S.dpuf

A GOAN RIPPLE IN DHOBI TALAO

Roana Maria Costa visits a club whose membership per day is less than the cost of a vada pav

It’s mid morning and Goa’s nightingale Lorna’s magnetic voice fills the air as she croons Tuzo Mog, a famous Goan classic.

In a little corner hidden behind a white sheet pinned up to cast off the heat sits James Rodrigues adjusting the volume knob on his CD player and watching the world go by. His shop, C F Rodrigues and Sons, in the business of selling Konkani CDs and VCDs for over 70 years, is stacked with music and tiatrs by Goa’s artists like Alfred Rose, C Alvares, Junior Rod, Jacinta Vaz and, of course, Lorna.

Rodrigues couldn’t have found a more perfect location than below 30-odd Goan clubs in Jer Mahal Estate. He knows his posters strategically placed advertising ‘Pisso Dotor’, a Konkani comedy, will find enough takers.

Easily one of Mumbai’s better chawls, Jer Mahal Estate at Dhobi Talao is a stone’s throw from Metro theatre and St Xavier’s College. Anyone could mistake this for one more old chawl especially when a huge board screams Great Punjab Hotel on the first floor. Even when you step through any of its five narrow entrances there are no telltale signs. But walk up the wooden staircase and peep into any of the rooms and you know that you are in the middle of Goanness. The flavour of the tiny state fills your senses. The air is sussegado and Konkani rules the airwaves.

The club system in Jer Mahal does not involve gyms and swimming pools. A club here is one or more rooms, which are more like huge halls where Goan Catholics put up. Each village from Goa has its own club. Some villages have more than one club, depending on how many waddos or zones it has. Most members are male and take refuge in their respective village clubs when new to the city.

Cruz D’Costa came to Mumbai when he was 19. Resident at the Majorda club for close to three decades, for him this is “a home away from home—a second home’’. He speaks passionately about his love for Goa and how he holds the “the record’’ for going home the maximum number of times in a year, “at least eight times’’. Taking the steps two at a time and greeting everyone he meets, Cruz speaks a typical South Goa, Salcette Konkani. He says that getting admission into the club is simple—you need to be Goan, Catholic and have an identification. Once you are a member, you can stay there as long as you want.

Every club has similar interiors: wooden or steel boxes called pattis that line the walls, shoe stands, iron boxes and TV sets. One characteristic feature is the painting or statue of the village patron saint. The saint occupies pride of place at the altar and his or her feast is celebrated annually. Each club also has its own kitchen and a block of bathrooms as well as toilets that may or may not be attached.

There are 200 Goan clubs in Mumbai spread over Dhobi Talao, Chira Bazaar, Crawford Market, Dockyard, Mazgaon and Dadar. Dhobi Talao houses the maximum number. These clubs or Kuds were set up in the 1920s when Goans started coming to the city in search of a livelihood. They mostly took jobs in hotels or as seamen and were charged a nominal lodging rate. Today, although the clubs may boast 10,000 members, the number of full-time residents has dropped sharply. This, despite the fact, that the rent per day is less than a vada pav. Most clubs charge members Rs 40 a month.

In Dinshaw Mahal, you find magician Praxis Remedios from the Guirim club. A resident for over two decades, Praxis says, “Not many Goans know about the club. Though accommodation is inexpensive, takers are few as there is no privacy. Everyone just puts their bedding on the floor for the night.’’ Praxis’s father came to the city in the early century as opportunities in Goa were few. He says, “Today, hardly any Goan wants to be in Mumbai for long. They see it as a gateway, to gain experience and move to the Gulf, US, UK or the ship. Unlike earlier, one can do most of the paperwork for immigration or to sail in Goa itself.’’ Cruz adds that people prefer to check into a hotel with their families even though the clubs offer a family room for Rs 50 a day.

Gilbert Pinto from the Bastora club laments that even up to five years ago his club had 25 full-time members, while today there are only three guest members. Jobs abroad and on the ship pay so much more, he says, that people prefer those to a life in Mumbai. Andrade Costa from the Nuvemcares club says this is second home to him, and today the building is better maintained than 10 years ago after its interiors were repaired.

Joel Fernandes lights up when you mention football. “It’s just an excuse for the whole club to sit together in their jerseys and root for their favourite team,’’ he says. “By the way, it’s Brazil,’’ he whispers with a smile.

With dwindling numbers,old customs like the evening rosary are dying.But veterans like Cruz and Praxis say that the clubs are still a great place to catch up on the gossip over an evening drink. Even though these residents have lived in Mumbai for decades their culture, speech and mannerisms have not changed. As you talk to Praxis, Gilbert, Joel or Cruz, one thing is clear—you can take a Goan out of Goa but you can’t take Goa out of a Goan.

Threat of demolition? Not yet There is confusion among the residents about whether the building, which is over a hundred years old, may be torn down. However, coordinator of the Jer Mahal Estate Forum Farookh Shokri squashes all such fearmongering. He explains that the building is a Grade III building, which means it can be demolished only if 70% of the tenants approve. That is not the case right now. The Forum is also pushing to make the building Grade II to ensure that its facade is protected. For this, the urban development ministry has to grant permission. Shokri says, “We are facing no threat or pressure from the developer.’’

President, Jer Mahal Tenants’ Residential Clubs Association, Thomas Sequeira says a builder, Rohan Developers, has bought the property and approached them to redevelop it but has not come up with a final plan.

stories of Bombay Goans

================================================

Between St Xavier’s College and Metro Cinema is a Grade-III heritage structure known

as Jer Mahal. A cluster of six buildings and an annexe, it represents the finest example

of a whole style of vernacular Indian architecture. It has even been called ‘Bombay’s

most beautiful chawl’.

A Goan cultural hub, Jer Mahal accommodates 50 Goan clubs on its premises at Dhobi

Talao. These clubs have been around for over a century; the oldest one can be traced

back to 1857. Each floor accommodates 3 to 4 clubs, along with a single kitchen and

a bathroom. Today, the clubs are characterised by broken walls, protruding cable wires

and worn out arches.

Lithograph of a view of Colaba by Jose M. Gonsalves (fl. 1826-c.1842) plate 3 from his 'Lithographic Views of Bombay' published in Bombay in 1826. Gonsalves, thought to be of Goan origin, was one of the first artists to practice lithography in Bombay and specialised in topographical views of the city. Colaba was originally the southernmost of Bombay's seven islands and named after the Koli fishermen who lived here. The island was visited by the English residents of Bombay for recreation from the 18th century and also used as a military cantonment in the 19th century. Colaba was connected to Bombay by a causeway that was only accessible at low tide by 1838. Within six years, Colaba became the new centre for the cotton trade

Asiatic Steam Company,

Between St Xavier’s College and Metro Cinema is a Grade-III heritage structure known

as Jer Mahal. A cluster of six buildings and an annexe, it represents the finest example

of a whole style of vernacular Indian architecture. It has even been called ‘Bombay’s

most beautiful chawl’.

A Goan cultural hub, Jer Mahal accommodates 50 Goan clubs on its premises at Dhobi

Talao. These clubs have been around for over a century; the oldest one can be traced

back to 1857. Each floor accommodates 3 to 4 clubs, along with a single kitchen and

a bathroom. Today, the clubs are characterised by broken walls, protruding cable wires

and worn out arches.

Club class

Published: Sunday, May 18, 2008, 3:40 IST

By Radhika Raj | |

......................................................................................................................

some make a quick buck selling 130 year++ old photos of 19 century!what is available in chor bazar from antique shops for 5oo rupees is being sold for 50000 and 60000 rupees

Mohammadi Mahal at the Junction of Kalbadevi Road and ...

Mohammadi Mahal at the Junction of Kalbadevi Road and ...

bombay100yearsago.com › ... › Bombay 100 Years Ago

......................................................................................................................

some make a quick buck selling 130 year++ old photos of 19 century!what is available in chor bazar from antique shops for 5oo rupees is being sold for 50000 and 60000 rupees

Mohammadi Mahal at the Junction of Kalbadevi Road and Girgaon

Mohammadi Mahal at the Junction of Kalbadevi Road ...

oldphotosbombay.blogspot.com › 2015/06 › mohamm...

Jun 27, 2015 — Mohammadi Mahal at the Junction of Kalbadevi Road & Girgaon[ Jer ... The Musings of a Night Owl: Jer Mahal - Glimpses of Mumbai - Part - II.

Oct 13, 2011 — Remedios is one of the residents of a Goan club at Jer Mahal in Dhobi Talao. “

Chic-Chocolate | Music-Directors | Music-Composers ... - Radio Citywww.planetradiocity.com/musicopedia/article-musicdir/Chic.../828Chic Chocolate had a flourishing career as a music composer in Bollywood movies. ...He is remembered for his work with Naasir in the 1956 film, Kar Bhala.

Also known as

Chick Chocolate, Antonio Xavier VazBrief Biography

Chic Chocolate had a flourishing career as a music composer in Bollywood movies. In 1951, he began his career as a music director with the movie Naadaan. He was an exceptional Goan Catholic musician. His speciality was western music.

Naadaan had a fantastic track list, including melodious songs like Talat's 'Aa Teri Tasviir Bana Lu' and Lata Mangeshkar’s unforgettable 'Sari Duniya Ko Piichhe Chodkar'.

Chic Chocolate was an integral part of composer C. Ramchandra's team. Their collaboration in the 1952 movie Rangeeli was a huge success, especially the song "Koi Dard Hamara Kya Samjhe, sung by Lata Mangeshkar was highly appreciated.

He worked as an assistant music director to Chitalkar for Sagai. Chic Chocolate also worked as an assistant with Madan Mohan and O. P. Nayyar. He is remembered for his work with Naasir in the 1956 film, Kar Bhala.

Discography

Naadaan

Rangeeli

Kar BhalaTriviaChic Chocolate’s favourite instrument was the trumpet.

Music composer Chic Chocolate died in 1967 at the age of 55, in Mumbai.

I Couldn’t Sleep a Wink Last Night was part of the soundtrack of the 1943 film Higher and Higher. It was recorded in Calcutta two years later by Chic Chocolate and his Music Makers and featured the band’s regular vocalist, Charles Sheppard.This track is from the Marco Pacci collection.

Lithograph of a view of Colaba by Jose M. Gonsalves (fl. 1826-c.1842) plate 3 from his 'Lithographic Views of Bombay' published in Bombay in 1826. Gonsalves, thought to be of Goan origin, was one of the first artists to practice lithography in Bombay and specialised in topographical views of the city. Colaba was originally the southernmost of Bombay's seven islands and named after the Koli fishermen who lived here. The island was visited by the English residents of Bombay for recreation from the 18th century and also used as a military cantonment in the 19th century. Colaba was connected to Bombay by a causeway that was only accessible at low tide by 1838. Within six years, Colaba became the new centre for the cotton trade

TRAVEL BY SHIP BEFORE 1960-- BOMBAY TO LONDON,EUROPE,CALCUTTA,GOA

The Asiatic Steam Company, employed a large percentage of local Officers that included Indian, Anglo-Indian, Burmese and Anglo-Burmese.an apprentice in 1946 EARNED:-In the first year of his apprenticeship he was paid 15 Rupees per month, the second year 30 Rupees a month, third year 45 Rupees rising to 60 Rupees for the fourth year. The deck crew did not come from the Maldives but from the Laccadives, more specifically Minicoy Island which is about 200 miles west of Cochin, the engineroom crew came from the Nhoakali District of East Bengal (now Bangladesh), carpenters were Chinese and the cabin stewards were from Calcutta. The crew did not eat Curry and potatoes for breakfast but enjoyed a balanced diet including Mutton, vegetables and Rice and like all ships crewed by their ilk ‘live’ supplies were also carried for their consumption such as chickens and sheep which were slaughtered as required because the ships had no refrigerators, running water or air conditioning.MAHARANI.Asiatic Steam Company,

Formed in 1878,ships were registered in either London or Liverpool its principle port of operation was Calcutta. Like British India’s eastern service ships once they had departed the United Kingdom they were never to return. The new company enjoyed the patronage of Messrs Thomas H. Ismay and William Imrie of Ismay, Imrie & Company, managers of Oceanic Steam Navigation Company known in the shipping world as the

White Star Line.

NURJAHAN.

Built: 1884 by Harland & Wolff Ltd, of Belfast.

Tonnage: 2,967 grt, 1,936 nt.

Wrecked near Cape Comorin whilst on passage Bombay to Calcutta on the 21st of November 1890.

The company increased its fleet to five in 1880 when Peshwa the company’s first 2,000 tonner was launched and two years later a further two ships were added to its number on the completion of Nurjahan and Kohinur the company’s first all steel ships.

NADIR

Built: 1889 by Harland & Wolff Ltd, Belfast.

Tonnage: 3,142 grt, 2,041 nt.

Engine: Single screw, Triple expansion by builder.The company decided to increase its sphere of trading and began operating services to Java and was also successful in tendering a contract with the Government to carry mails to the Andaman Islands, however there was a downside, they

also became responsible for the transportation of convicts to the penal settlement at Port Blair situated on South Andaman.

PRISON CELLS BELOW DECK

By now Ceylon and Malaya had entered onto the company’s trade routes with principle cargoes being made up of teak, coal, sugar, rice and of course its usual carriage of native deck passengers.

DECK PASSENGERS MIDSHIP

©D. BEEDLE.

DECK PASSENGERS TWEEN DECK. ©D. BEEDLE.

DECK PASSENGERS SLEEPING ARRANGEMENTS.

DECK CARGO OF BUFFALO

D LAST BUT NOT LEAST , LADIES AND GENTLEMEN, YOUR PASSENGES AWIT.

Vasna Boatdeck

Vasna Chartroom

Vasna First class lounge

Vasna First Class lounge

Vasna Bridge

Officers Vasna

PUNDIT

©D. BEEDLE.

Built: 1919 by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson, Ltd, Newcastle.

Tonnage: 5,305 grt, 3,199 nt.

Photo dated November 1951.

©D. BEEDLE.

Built: 1922 by Lithgows, Ltd, Glasgow.

Tonnage: 5,843 grt, 3,656 nt.

Built: 1923 by Charles Connell & Co., Ltd, Glasgow.RAJPUT

Photograph dated July 1947.MAHARAJA.

Photograph dated March 1956

15th of November 1940, Ranee fell victim to a mine when in the Suez Canal on the 5th of February 1941.

RANEE SUNK IN SUEZ CANAL;ANDShahzada lasted a year longer than her sister when she was sunk on the 9th of July 1944 by torpedo 500 miles west of Goa

Subadur, sank by torpedo and gunfire from unknown submarine on the 7th of April 1942, 170 miles north west of Bombay in the Arabian Sea.BAHADUR

HAVILDAR

Built: 1940 by Lithgows Ltd., Port Glasgow.

Tonnage: 5,407g, 3,1

SHAHJEHAN

Built: 1946 by Lithgows Ltd., Port Glasgow.

Tonnage: 5,460 g, 3,210 n.

LOADING COAL AT GARDEN REACH.1947to load 7,000 tons using local labour would take approximately two days, note in these photo’s there are no women or children present, whereas the norm was for them to be working alongside the men, also note the lack of footwear. After tipping the coal into the hold trimmers down below would spread it to the sides of the ship, I think its fair to say that conditions for the trimmers must have been quite appalling. After discharging their baskets the carriers would drop them on deck to be returned by yet more labour and proceed to the bunker station for another load, for their efforts remuneration was about four Rupees a day.

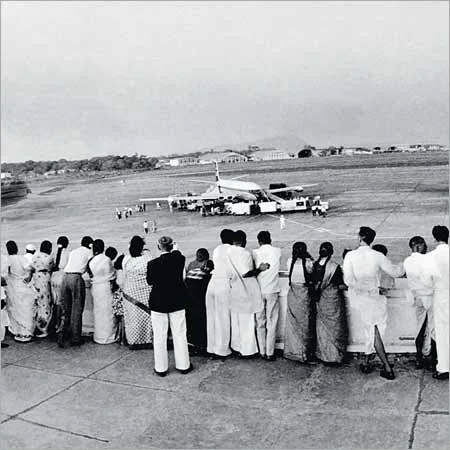

Air travel started in 1950 from JUHU airport Bombay(Mumbai) used super constellation planes made by Lockheed with four propellers

BEFORE 1950 AIR TRAVEL WAS VERY DIFFICULT AND TEDIOUS; USED TO TAKE 6 DAYS BY PLANE FROM LONDON TO BOMBAY

Imperial Airways : The Definitive Newsreel History 1924-1939 - Civil Aviation

www.strikeforcetv.com This is the definitive celebration of Britain s first national airline Imperial Airways. Imperial Airways were the ...

Imperial Airways at Croydon Aerodrome in 1924. Film 8358

Imperial Airways. Croydon airport in 1924. Lovely shots of ground crew preparing passenger bi-planes for take off. Amusing air ...

LARGE SCALE RC IMPERIAL AIRWAYS HP42 "HELENA" LMA RC MODEL AIRSHOW AT RAF COSFORD - 2013

FILMED AT AN RC MODEL AIRCRAFT SHOW RUN BY THE LMA ( LARGE MODEL ASSOCIATION ) AT RAF COSFORD ...- HD

BELOW-INDIA'S FIRST JET ENGINED PASSENGER PLANE AT SANTA CRUZ ;21 February 1960 when first Boeing 707–420, named Gauri Shankar (registered VT-DJJ), was delivered,(OBSERVE THE DRESS AND FASHION OF BOMBAY AT THAT TIME -ONLY SAREE FOR WOMEN,white shirt and white pants for men)

AIRPORT BOMBAY

Air India - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Air_India----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Category: Bombay, Hindi film music, Jazz

TUESDAY, SEPTEMBER 30, 2008

Bombay to Goa - The Little Odyssey

THE LITTLE ODYSSEY

Bombay (now Mumbai) has been a second home to many Goans who have lived and worked there for generations. Nevertheless, they have not lost touch or their love for Goa. During the months of April and May, entire families will flock to Goa for their annual summer holiday along with their kids, soon after school final examinations. These two months have traditionally been the most enjoyable months, full of fun and frolic for everyone. The purpose of visits are many-fold; some of them are to get away from city life, holiday for parents and the kids, while other reasons are to carry out necessary repairs to ancestral homes and visit their loved ones. In the old days, many of us looked forward for such holidays. It would be an unforgettable experience. For most people the modes of transport to travel for this holiday was by steamer and bus, and to some by rail and air. Of all these, traveling by ship was the most popular and full of excitement. It was as though one large Goan family of more than five hundred members traveled for one mega holiday to one common destination: GOA. Here is my own experience.

Bombay (now Mumbai) has been a second home to many Goans who have lived and worked there for generations. Nevertheless, they have not lost touch or their love for Goa. During the months of April and May, entire families will flock to Goa for their annual summer holiday along with their kids, soon after school final examinations. These two months have traditionally been the most enjoyable months, full of fun and frolic for everyone. The purpose of visits are many-fold; some of them are to get away from city life, holiday for parents and the kids, while other reasons are to carry out necessary repairs to ancestral homes and visit their loved ones. In the old days, many of us looked forward for such holidays. It would be an unforgettable experience. For most people the modes of transport to travel for this holiday was by steamer and bus, and to some by rail and air. Of all these, traveling by ship was the most popular and full of excitement. It was as though one large Goan family of more than five hundred members traveled for one mega holiday to one common destination: GOA. Here is my own experience.

It was the month of February

Not losing count of any single day

In quite a hurry

I seemed to be;

Thoughts of getting away

From life in the city

Of bright lights

Bus, tramcar and train

Far away from the hustle

And bustle of Churchgate,

Fort and Flora Fountain.

Endless waiting

Thoughts of remaining days of school

And final term examinations

Seemed never ending;

Not losing count of any single day

In quite a hurry

I seemed to be;

Thoughts of getting away

From life in the city

Of bright lights

Bus, tramcar and train

Far away from the hustle

And bustle of Churchgate,

Fort and Flora Fountain.

Endless waiting

Thoughts of remaining days of school

And final term examinations

Seemed never ending;

Thoughts of mangoes

Jackfruit and cashew apples

Were in the offing

Their aroma I imagined

And was for a while lost

In far away thoughts

And awakened by the sudden screech

Of the speeding train.

“Just one more month, son”

Mum and Dad seemed to comfort;

Dad has his suitcase

And holdall at the ready;

Mum has already been shopping

For summer wear

At the local market fair.

Tickets are booked

Dad has made sure of that

“We will be going by steamer” he said.

“Aunty Pam and kids will join us too”

Said Mum in the summer of nineteen seventy-two.

The day to leave for Goa

Has finally arrived

The Ambassador taxi

Is waiting down by the kerb-side.

Off to Ballard Pier before dawn we head

And on board our place we finally get

The steamer’s deck is full;

There seems to be quite a din,

Each in their own place,

The great journey is about to begin.

Jackfruit and cashew apples

Were in the offing

Their aroma I imagined

And was for a while lost

In far away thoughts

And awakened by the sudden screech

Of the speeding train.

“Just one more month, son”

Mum and Dad seemed to comfort;

Dad has his suitcase

And holdall at the ready;

Mum has already been shopping

For summer wear

At the local market fair.

Tickets are booked

Dad has made sure of that

“We will be going by steamer” he said.

“Aunty Pam and kids will join us too”

Said Mum in the summer of nineteen seventy-two.

The day to leave for Goa

Has finally arrived

The Ambassador taxi

Is waiting down by the kerb-side.

Off to Ballard Pier before dawn we head

And on board our place we finally get

The steamer’s deck is full;

There seems to be quite a din,

Each in their own place,

The great journey is about to begin.

The ship sounds its siren,

With a mighty roar

As it lift its anchor;

There’s slight rumble on deck

As tugs pulls it out to sea;

In the distance the majestic grandeur

And awesome structure

Of this landmark Gateway of India

Grew smaller and smaller.

Soon we head south

Along the hazy coast on our left,

On the right we see the huge expanse

Of the Arabian Sea;

While for some at the start

Of the twenty-four hour journey

Seems to be to quite dizzy,

Slight pitching of the ship

Only a short-lived agony;

Others are quite at ease and jolly

Perhaps having traveled

So many times before

That they lost count

In their memory.

It is midday out at Sea

Ship’s canteen is busy;

Gathered on the aft deck

It’s a hot summer’s day

A bunch of teenagers

Have already got started

With their guitars tuned;

Joined in shortly with some new friends

They have a go with the first round

It’s the beginning of our summer holiday

With the popular hits of the times

Of Cliff Richard and the Shadows

Bachelor Boy and Young Ones.

With a mighty roar

As it lift its anchor;

There’s slight rumble on deck

As tugs pulls it out to sea;

In the distance the majestic grandeur

And awesome structure

Of this landmark Gateway of India

Grew smaller and smaller.

Soon we head south

Along the hazy coast on our left,

On the right we see the huge expanse

Of the Arabian Sea;

While for some at the start

Of the twenty-four hour journey

Seems to be to quite dizzy,

Slight pitching of the ship

Only a short-lived agony;

Others are quite at ease and jolly

Perhaps having traveled

So many times before

That they lost count

In their memory.

It is midday out at Sea

Ship’s canteen is busy;

Gathered on the aft deck

It’s a hot summer’s day

A bunch of teenagers

Have already got started

With their guitars tuned;

Joined in shortly with some new friends

They have a go with the first round

It’s the beginning of our summer holiday

With the popular hits of the times

Of Cliff Richard and the Shadows

Bachelor Boy and Young Ones.

Its evening

With breeze from the south-west

There is a slight lull on deck;

The ocean’s waves are high

It seems the ship’s constant roll

Had its toll

For many are now relaxed

After a short snooze.

Silhouettes of seagulls at sunset

Formed flying patterns,

As the passing ship heading north

On our starboard side

Seemed to bellow

With its siren a huge hello;

Promptly acknowledged

By our ship that woke up

Many a tired fellow.

It was supper time

The silvery moon

Seemed to smile

With its reflection

On the starboard side

Leaning on the rail

We took it all in

And young men sang

Lilting melodies of moon songs

As we sailed along in the splendid night.

Astern the moon lit up

A white trail of surf in its wake;

Aft deck above the horizon

The Pole Star

Posed as a direction finder

Amidst the seven bright stars

Spanning the northern skies

In the mighty constellation

Of the Great Bear.

With breeze from the south-west

There is a slight lull on deck;

The ocean’s waves are high

It seems the ship’s constant roll

Had its toll

For many are now relaxed

After a short snooze.

Silhouettes of seagulls at sunset

Formed flying patterns,

As the passing ship heading north

On our starboard side

Seemed to bellow

With its siren a huge hello;

Promptly acknowledged

By our ship that woke up

Many a tired fellow.

It was supper time

The silvery moon

Seemed to smile

With its reflection

On the starboard side

Leaning on the rail

We took it all in

And young men sang

Lilting melodies of moon songs

As we sailed along in the splendid night.

Astern the moon lit up

A white trail of surf in its wake;

Aft deck above the horizon

The Pole Star

Posed as a direction finder

Amidst the seven bright stars

Spanning the northern skies

In the mighty constellation

Of the Great Bear.

Fishing line cast out into the sea

A lone sailor

A lone sailor

Joined us later

As he stared into the dark horizon

And before everyone fell asleep

Narrated mariner’s stories,

Great travel adventures and life at sea.

Dreams on the upper deck that night were plenty

If fact a huge string of them,

Happy and lengthy;

Thoughts of Calangute,

Colva and Miramar beach

Friday Mapusa Bazaar;

Visits to Goa Velha

And Dona Paula.

After a marathon journey and a long night

The sun seemed to be in no hurry to rise,

The landscape seemed familiar

Something I have seen in the years earlier

Dad pointed out to me

The distant forts of Tiracol and Chapora

And the oldest lighthouse of Asia

At Fort Aguada;

He seemed to hold court

For almost everyone on

On the ship’s portside

As we to our destination

Were getting closer .

The ship glided gently

Through the delta and sandbar

At the mouth of the Mandovi River

Edging towards the quay

Some admire the beauty

Of the city of Pangim

To our left other admire

The beauty of the hills of Betim.

And before everyone fell asleep

Narrated mariner’s stories,

Great travel adventures and life at sea.

Dreams on the upper deck that night were plenty

If fact a huge string of them,

Happy and lengthy;

Thoughts of Calangute,

Colva and Miramar beach

Friday Mapusa Bazaar;

Visits to Goa Velha

And Dona Paula.

After a marathon journey and a long night

The sun seemed to be in no hurry to rise,

The landscape seemed familiar

Something I have seen in the years earlier

Dad pointed out to me

The distant forts of Tiracol and Chapora

And the oldest lighthouse of Asia

At Fort Aguada;

He seemed to hold court

For almost everyone on

On the ship’s portside

As we to our destination

Were getting closer .

The ship glided gently

Through the delta and sandbar

At the mouth of the Mandovi River

Edging towards the quay

Some admire the beauty

Of the city of Pangim

To our left other admire

The beauty of the hills of Betim.

Dreams will shortly turn into reality

Uncle Seby will come

To fetch us hopefully

In a reserved ‘Opel Rekord’ taxi

Taking us to our ancestral home finally

With an experience of what seemed to be

A little odyssey.

Uncle Seby will come

To fetch us hopefully

In a reserved ‘Opel Rekord’ taxi

Taking us to our ancestral home finally

With an experience of what seemed to be

A little odyssey.

Excerpt | Long gone blues

Excerpt | Long gone blues

Swing time: The Mickey Correa band at the Taj hotel, circa 1939. Photographs courtesy Naresh Fernandes from his book Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombay’s Jazz Age (Roli Books)

Updated: Sat, Dec 03 2011. 12 10 PM IST

As a teenager in the Goan village of Curchorem, Franklin

Fernandes spent long hours practising the trumpet with only one goal in

mind: he wanted to “play like a negro”. It wasn’t an ambition his

teacher, Maestro Diego Rodrigues, would have understood. Like all

teachers in Goa’s parochial schools, Rodrigues coached his charges in

musical theory and instructed them in the art of playing hymns and

Western classical music.

Swing

time: The Mickey Correa band at the Taj hotel, circa 1939. Photographs

courtesy Naresh Fernandes from his book Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of

Bombay’s Jazz Age (Roli Books)

It was all very baffling. “But when we heard the records,

we knew how to play the notes,” Fernandes said. The thick shellac

records that set him off on his journey of discovery bore the names of

Ellington, Armstrong and Cab Calloway, and Fernandes grew addicted to

hot music. Jazz, he said, gave him “freedom of expression”. He still

looked at the sheet music, of course, but he knew that it could take him

only so far. “Like Indian music, jazz can’t be written,” he said. “You

have to feel it. There are 12 bars, but each musician plays it

differently. You play as you feel—morning you play different, evening

you play different.”

Frank Fernandes grew so enamoured of the new music from

America that in 1936, aged 16, he decided to make jazz his life. He

headed to Bombay, where, like so many other Goans, he hoped to find work

in one of the city’s famous dance bands. Of course, it wasn’t quite so

easy. Competition for jobs was intense, so Fernandes—who would soon

adopt the stage name Frank Fernand—began to work for the Bata shoe

company in Mazagaon for 12 annas a day. After work, he performed at the

amateur nights at Green’s hotel, hoping to attract the attention of

someone who mattered.

Singer Pamela McCarthy.

Like Fernand, other Indian musicians had also come to

value the freedom that jazz allowed them. Indians had been playing hot

music, with varying degrees of proficiency since the 1920s. In 1937,

when Teddy Weatherford took over leadership of the band at the Taj from

Crickett Smith, as age began to catch up with the trumpet player,

several Indians had become skilful enough to play alongside the

African-Americans. A photo of Weatherford’s band from 1938 shows three

Indians looking out from behind their instruments. Two of them were

brothers: Hal and Henry Green, from Bangalore. Their father, Cecil

Beaumont Green, was an army surgeon who had fought in the Boer War

before becoming the personal physician of the ruler of Mysore. Hal

Green, the fourth of the doctor’s six children, had begun his musical

education on a reproduction copy of a Stradivarius that his father had

given him. He was an autodidact. He devoured American films and records

to learn as much as he could about ragtime and Dixieland music, also

teaching himself about European classical music on the side.

Before they joined the Weatherford band, Hal Green and

his younger brother Henry had led the eightmember Elite Aces at the Taj

in 1933, performing what Ali Rajabally described as dance music with a

jazz accent. Hal Green played guitar, reeds and the violin, while Henry

was a bassist and saxophonist. “The type of music they had brought with

them may be an overworked cliché today but it was an unheard of

departure then,” Rajabally wrote. “Night after night, Hal and his alto

sax drove the band through performances so exultantly searing that no

band in the country, local or foreign, could have successfully

challenged them for the No. 1 spot.”

The Correa Optimists in the early 1930s.

In 1939, the outbreak of World War II in Europe shook up

Bombay too. As barrage balloons went up over the Oval maidan like “a

school of enormous airborne white whales”, in the description of one

young observer, German and Italian residents were taken into custody or

fled the country. Beppo di Siati, Frank Fernand’s Italian bandleader at

Majestic Hotel, was among the enemy nationals interned. As the conflict

spread, Bombay became the temporary home to troops from Australia, New

Zealand, Canada and England, passing through from the Eastern front to

Africa and Europe and for soldiers from the Western theatre of war on

their way to the Far East. The journalist Dosoo Karaka observed the

influx with his usual cynicism. “The city,” he wrote, “was a halfway

house for the cannon fodder of [the] great war.”

En route to the front, the soldiers created quite a

commotion. One observer recalls Australian troops commandeering the

horse-drawn Victoria carriages that thronged the street outside the Taj,

pushing the driver into the backseat and racing one another through

downtown Bombay. “The crowds roared their applause,” he wrote. “The

Aussies could have perpetrated more danger in Bombay than they did on

the battlefield.” The arrivals weren’t all male. Allied officers brought

their wives, while other Englishwomen realised that it would be prudent

to wait out the war in the safety of India. There were refugees

too—Poles, Danes, Czechs and Jews from Germany and Eastern Europe.

Karaka went into a funk and couldn’t bear to listen to

any music at all. He became addicted to the wireless. “The news

bulletins were the funeral marches of our modern composers—the men of

the Hood, the men of Dunkirk, the men who died in the huge craters of

Crete. That was the music of this generation—the music we were destined

to hear,” he wrote. “Music that was written on the casualty lists, the

dead being the flats and the wounded with their anguished cry being the

sharps.”

A view of early 20th century south Bombay.

The most durable of all the war-time bands was headed by

Micky Correa, a saxophonist born in Mombassa who had perfected his craft

in Karachi with his family band, the Correa Optimists. When he moved to

Bombay in 1937, he played with Beppo di Siati’s Rhythm Orchestra at the

Eros Ballroom, famed for its sprung dance floor. At the band’s next

engagement, at the Majestic Hotel, he performed alongside Frank Fernand

and shared a room with the trumpeter in Dhobi Talao. In 1939, Correa

formed his own band at the Taj—and set a record of sorts by staying

there until 1961. Perhaps the longevity of his stint at the Taj was the

result of his physical endurance. Correa prided himself on his fitness

and exercised regularly with dumbbells, following the techniques devised

by the Canadian bodybuilder Joe Weider. He also knew how to please a

crowd, never turning down requests. The Taj publicity brochures

described Correa as a musician who was “untired of repetitions”.

Correa’s orchestra at the Taj was a hothouse for Bombay

swing. The men and women who would go on to lead the city’s most popular

groups found early encouragement on his bandstand: saxophonists Johnny

Baptist, Norman Mobsby, George Pacheco and the Gomes brothers, Johnny

and Joe; trumpet players Peter Monsorate, Pete D’Mello and Chic

Chocolate; and pianists Manuel Nunes, Dorothy Clarke and Lucilla

Pacheco, among others. Recalled Ali Rajabally: “The Bombay jazz scene

was honeycombed with virtuosi of high calibre. The pace was intense, but

it was carried on in a spirit which placed the love of jazz above every

other consideration. Nobody played with one eye on the cash-box and the

other on the clock.”

The cover of Taj Mahal Foxtrot.

Cotton started by playing the trumpet, but decided to

dump his horn after dropping by the Taj one day in 1936 and being

captivated by the smooth tenor sax of Cass McCord. He was an early

follower of Lester Young. “In those days, Rudy was often criticised for

having a soft, what is known today as a ‘cool’ tone,” an amateur

musician named Rusi Sethna told Blue Rhythm magazine later. “Rudy

belonged to the modern school of tenor playing but that term came into

being recently while Rudy has been blowing like that ever since I can

remember.”

Rudy Cotton’s big break came when he was hired by Tony

Nunes, the pianist who headed the Teetotallers band, but he credited his

ability to really “feel jazz” to the stint he spent in the orchestra of

Vincent Cummine, playing alongside such talents as Cummine’s violinist

brother Ken, the bassist Fernando “Bimbo” D’Costa, the drummer Leslie

Weeks and the spectacular trumpet player Antonio Xavier Vaz, who was

already winning legions of fans under his stage name Chic Chocolate.

Cummine’s band travelled to Rangoon in 1938, but by 1940, Cotton had

formed his own group, persuading his former bandmates to join him, and

adding Sollo Jacobs on piano.

“As anyone who knows the history of Indian orchestras can

well imagine, this combination proved a tremendous success overnight

and from then onwards Rudy’s fame was on the upbeat,” The Onlooker magazine reported. Bookings poured in from the Taj, the Majestic and the Ritz, among other establishments.

Toot

your horn: Parsi musician Rudy Cotton, born Cawasji Khatau, became a

musical force on a scene dominated by Goans and Anglo-Indians.

The busiest of all the war-era bands was led by the

inimitable Ken Mac, who had managed to retain his hold on the Bombay

dance-music scene long after Leon Abbey’s departure. By the mid-1940s,

Mac was being signed up for about 40 engagements a month. Every

Wednesday, he played regular shows at the YMCA on Wodehouse Road for

Allied troops. His crooner at that time was Jean Statham, whom he later

married. Occasionally, his young niece, Pamela McCarthy, would sing a

tune or two. She had been stricken with polio at the age of 11 and

performed from her wheelchair, dressed in a glamorous ball gown. It was a

hectic life. “Music and dancing was so popular and we played all the

top venues—the Taj, Ambassador and Ritz Hotels, the Radio, Willingdon,

Yacht Clubs and Bombay Gymkhana to name a few,” said McCarthy.

“Sometimes we did two sessions a day—an evening dance and later a night

dance.”

Mac also made regular radio broadcasts and cut dozens of swing-tinted records. The first, “Down Argentina Way”,

sold more than 25,000 copies. Mac told one interviewer that there was

much more to being a successful bandleader than merely having to ensure

that the musicians played the right note at the right time. “He is the

band’s star salesman who must obtain the most favourable terms,” the

journalist wrote. “He has to make sure the boys will meet always on time

and are dressed as they should be. He has to exercise tact and good

temper to smooth out frictions and difficulties. He is responsible for

building up the library—as the sum total of all the band numbers is

called.”

Bombay’s band leaders obtained their music from

publishing houses and from local cinema distributors, and listened hard

to the radio and to new records. All the best bands had their own

arrangers, men who wrote the parts of each instrumentalist in a unique

way so as to make their outfit’s version of standard tunes stand out

from their competitors’. Indian musicians were also beginning to compose

their own tunes. Pianist Sollo Jacob had written a foxtrot called

“Everyone Knew”; Hal Green, already a much-in-demand arranger, had

composed tunes he called “Copacabana” and “Get Out of the Mood and Into

the Groove”, while Chic Chocolate was performing his “Juhu Jive”.

Naresh Fernandes is a consulting editor at Time Out India. This is his first book.

Excerpted from Taj Mahal Foxtrot: The Story of Bombay’s Jazz Age

by Naresh Fernandes; published by Roli Books, accompanied by a CD of

original recordings, 192 pages, Rs 1,295 (the book may be pre-ordered on

Flipkart.com). Taj Mahal Foxtrot will be released on 20 December.

FRIDAY, JULY 17, 2009

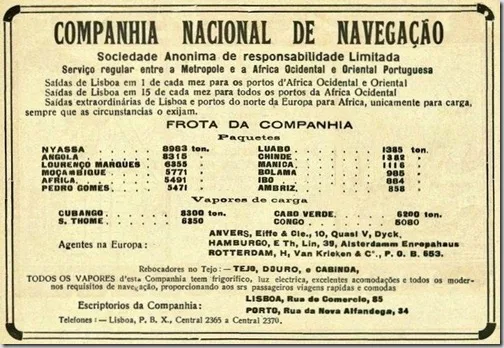

Companhia Nacional de Navegacao

India 45:India, in service 1951-71, 7631 grt, 387 passengers Unidentified commercial card of India - number 2 of series 18.

BI Logbook

www.biship.com

Karoa (BI 1915-1950), one of three Swan Hunter built, K class ships for the Bombay-East Africa/South Africa service

Konkani Videos==================================================== , =================================================== ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ BOMBAY GOANS-1920-1980-[2]

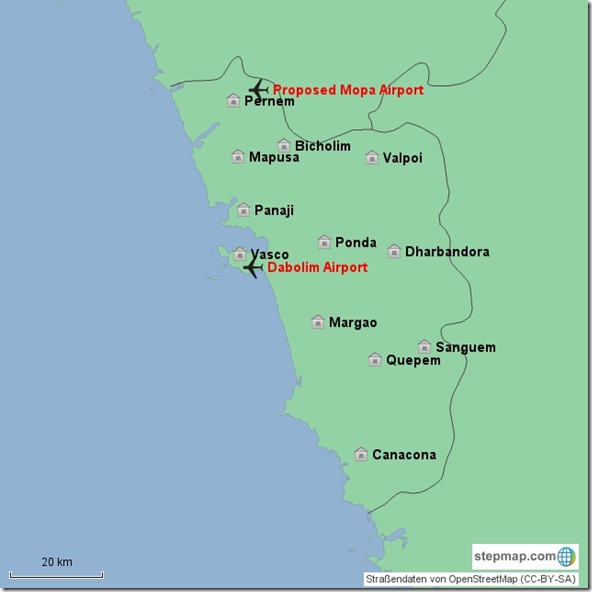

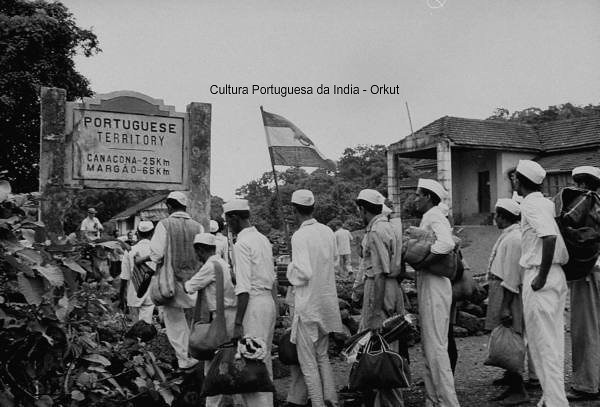

When crossing from Goa to India needed a visa

As New Delhi intensified pressure on

Lisbon in the 1950s to hand over its territories in Portuguese India,

Goans on the move had to surmount all sorts of bureaucratic hurdles.

Polem was where Goa ended and India began, as the soil went from brown to red. When I first arrived in Polem in 1956, the Portuguese immigration staff was largely of European origin.  Checks were carried out way beyond sunset, and if you missed the last bus to Margão  you could sleep in the verandah of a little restaurant near the check post or under the trees. The restaurant served xitt-koddi, fried bangdas, tisreos (clams), spicy xacuti and tender coconut water, along with a host of Portuguese wines – a small Vinho Porto cost eight tangas (eight annas or fifty paise). On two occasions, I carried a bed-sheet and timed my entry into Polem only for the experience. The leftover passengers made friends easily and broke into mandos, music goan band tidal wave playing portuguese n goan mando..mov

www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvuFF6eNALI

Nov 17, 2011 - Uploaded by Camilo Fernandes

goan band tidal wave playing portuguese n goan mando..mov .... konkani music at verna summer fete 2012 ...Mando - Dances of Goa - YouTube

www.youtube.com/watch?v=GO72ZueZuRM

Aug 20, 2013 - Uploaded by Cidade de Goa

As part of the musical accompaniment, the Mando also saw the East-West ... goan band TIDAL WAVE .fados music Fado, Music of Portugal - YouTube

www.youtube.com/watch?v=sFjeMZomano

Jul 31, 2013 - Uploaded by Viking Cruises

Born along the waterfront, the dramatic songs of Fado speak of life, struggle and passion. The genre originated ...Sonia Shirsat .. . Goan Fado singer - YouTube

www.youtube.com/watch?v=sdjuPINeBek

May 12, 2009 - Uploaded by Frederick FN Noronha

The lady with the powerful voice. A Cesera Evora in the making... From the Sigmund and Friends concert, May ...visited the post and ordered a spacious shed with toilets to be built there. The passport system On the other side of a hillock stood the Indian Customs office, a British-style building with a trellis frontage. Passenger baggage was checked in a shed outside the building next to a snack bar that served tea and samosas, and was frequented by office staff and porters. Those entering Goa via Karwar usually ate breakfast before setting out, and those leaving Goa carried staples like roast pork or  chicken cafreal, pão and bananas. The immigration and customs posts stayed open from 10 am to 6 pm, all through the week. Those whose travel documents could not be processed had to return to Karwar. But if you were on the blacklist for being pro-Portuguese, you were deported to Goa regardless of your documents. In February 1950, India presented its first aide-memoire to Portugal to discuss the handover of its territories, but Portugal replied that their future was non-negotiable. India allowed for a peaceful Exposition of St Francis Xavier’s relics in Old Goa from November 25, 1952 to January 6, 1953. The Bombay State Road Transport Corporation was permitted to ply its luxury buses right from the Belgaum railway station up to Panjim, which had a neat booking office. But hardly had the Exposition ended, that Delhi started dispatching shriller aide-mémoires to Portugal for an immediate handover of its territories. India shut its legation in Lisbon from June 11, 1953, and started to mount pressure, both territorially and on Portuguese Indian-born emigrants working in India. Bombay was host to some 400 Goan clubs that provided Goans dormitory accommodation at a pittance. At a certain stage, these clubs were required by the Bombay Police to maintain registers under the Foreigners Act, 1946. From October 1953, all Portuguese European officials were required to possess permits or visas to enter Indian territory; and in February 1954, this rule was extended to Portuguese officials of Indian origin. On July 31, 1954, Portugal announced that all Indian citizens entering its territories would have to possess a passport or an equivalent document, stamped with a visa from the Portuguese consular authority. India promptly made it mandatory for Portuguese citizens from the colonies who were entering the country to have permits from the Indian Consulate General in Panjim. Those proposing to enter India on Portuguese passports needed Indian visas, and had to be registered at the nearest Foreigners Registration Office before getting residential permits.  From August 1, 1954, the local Portuguese civil administrations of Goa, Damão and Diu, began issuing a bilingual transit permit, the Documento Para Viagem to Portuguese citizens travelling to India. The Portuguese passport and DPV had to be stamped by the district police headquarters before exiting Portuguese territory. This endorsement was valid for a week.  Those travelling to Portuguese territories were issued an Emergency Certificate printed on a sheet of brown paper by the Passport Office in Bombay. This certificate was valid for a fortnight, though it invariably expired by the time the Portuguese Consulate General processed the visa, in consultation with authorities in Goa.  BLOG DE LESTE: 50 ANOS! BLOG DE LESTE: 50 ANOS!

These are Portuguese India 1952 First Day Cover and Maxim Card of 400th Death Anniversary of Francisco Xavier in my collection.

On August 1, 1954, shipping and road transport services to Goa came to a halt. A year later, the meter-gauge train that ran from Poona to Goa via Londa Steam locomotive train service Goa to Bombay, longest ...

www.youtube.com/watch?v=4_W12X5J8zo

Dec 19, 2010 - Uploaded by torontochap1

circa 1985, margao train station and bombay to goa train arrival/departure at ... 0-Steam train at Margao Station, longest running service in ...

www.youtube.com/watch?v=tkeM0yiqoFM

Dec 19, 2010 - Uploaded by torontochap1

... this train at margao railway station headed to vasco terminal, goa. train ... Steam locomotive train ...also came to a standstill. At Castle Rock  and Collem stations, passengers were put through immigration checks and their passports and travel documents were stamped. At Caranzol, the first station in Goa,  I recall a strapping white Portuguese immigration official with an automatic rifle strapped to his chest verify my visa on the train with due courtesy. On arriving in Goa, one of the few objects to be taxed were playing cards – they were impressed upon by a Portuguese customs stamp. Foreigners had to report to the district police headquarters in Goa. As a British citizen, I was graciously assisted by the Portuguese-speaking regedor of Ucassaim, Chintamani Gaitonde, in extending my fortnight-long stay in Goa. Satyagraha The August 15, 1954, satyagraha to Goa flopped with barely a hundred Goan volunteers gate-crashing. But a year later, Delhi aided and abetted a much more formidable satyagraha of thousands of Indians, hoping that locals in Goa would rise in revolt. But Goans were of a different psyche and could not be mob-roused by outsiders who had not realised that the political scenario in Goa was very different from that in India during the independence movement. Despite bloodshed, life moved on so peacefully that Pandit Nehru told the Rajya Sabha on September 7, 1955, that India was not prepared to tolerate Portuguese presence, even if Goans wanted them there. The blockade and a chink On August 6, 1955, the Portuguese legation in Delhi was ordered shut and Portuguese interests were entrusted to the Brazilian Embassy there. On September 1, 1955, a diplomatic, economic, post and telegraph, and travel blockade came into effect between India and Portuguese territories. Mail from Goa to the rest of India was routed via Karachi in Pakistani mail bags, but mail to Goa was redirected to the sender even if the address was under-scribed via Karachi, Pakistan. However, by November 1955, the Universal Postal Union international protocol prevailed, and censored mail began to move via the southern-most land posts of Majali and Polem. Around April 1954, India began issuing ad-hoc permits on compassionate grounds through the Bombay state government, regulated by the Ministry of External Affairs’ Goa office in the Bombay Secretariat. Every applicant had to be interviewed by the MEA chief, Ashok N Mehta, an Indian Foreign Service officer and son-in-law of Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit. My friend, Benito de Sousa, was bluntly informed by Mehta that he could reach Goa only via Karachi, as he was a British passport holder. When my turn came, Mehta asked me, “Do you not know that foreigners are not allowed anywhere near the Goa border?” “Yes, I am aware, but I seek this permit on compassionate grounds,” I replied. “I have to visit my grandmother in Goa, as my father is tied to his work in Aden.” “Alright,” said Mehta, “I shall see.” A few days after returning to Poona, I was surprised by a brown envelope affixed with an official service postage stamp. It carried a letter permitting me to travel to Goa via Majali for a non-specified period. The Indian overland route permit Taking leave of my grandmother, uncle and aunt, I boarded the 10 pm Bangalore Mail and arrived in Belgaum at around 6 am on May 30, 1956. Within half-an-hour, I got onto the Bombay State Transport bus to Karwar. It was a nine-hour journey through winding ghats offering unparalleled natural vistas, but the journey weighed heavily on my digestive system. At Karwar, I was faced with a choice of only two hotels – the posh Sea Face Hotel and Hotel Rodrigues in the shopping centre. Being low on cash, I chose the latter and for five rupees got an apology for a room with sack-cloth walls and a bedful of bugs. The toilet were mercifully separated from the bathroom. On the morning of May 30, 1956, I boarded the bus for Kodibag, carrying a green steel trunk. It was a 45-minute ride through palm-fringed roads lined with pretty cottages. From Kodibag to Sadashivgad, from where you caught a bus to Majali, was a creek to negotiate by launch – a rather crude one when compared to ferries in Goa. After a stopover at Majali village, the bus proceeded to the immigration post where I was offloaded with a teenage girl and boy. Both these students had declared in an affidavit that they were moving to Goa for good. At the Indian customs post, I was ordered to surrender my money – 43 rupees, two annas and three pice – against a receipt valid for four months. If I failed to return before its expiry, the money would be gifted to the Government of India, they said. Such perfidy, I fumed. We cooled our heels for 45 minutes till the Indian immigration officer showed up. “Did you state in your application for this permit that you possessed a foreign passport?” he asked, looking at my British passport. “Yes,” I replied, handing him a copy of my application. He stamped the brown permit, but not the passport. My new found companions and I walked about two furlongs – over 400 meters – along no-man’s land. We then went through a gate and stopped at a police check-post before crossing the international line and entering the Goa Gate in Polem. All three of us were bankrupt, and to worsen matters the fund from which Portuguese border authorities offered five rupias gratis to every stranded passenger had already been exhausted. So the uncle of one of my companions loaned me five rupias which I promised to return, noting his Goa address in my diary. The same afternoon, my companions and I boarded the bus to Margão, a two-hour ride through largely virgin forest and past an impressive temple. At Canacona, a district police officer stopped the bus and called out my name. He had been telegraphed by Polém, about the presence of a foreigner, and after politely checking the entry stamp on my passport, he allowed us to proceed. In Margão, I decided to take the shortest route home to Ucassaim, via the Cortalim-Agaçaim and Panjim-Betim ferry crossings. I reached Panjim at sunset, emerging a curiosity with a trunk that belied my journey from India – a rarity during the blockade. One good soul, who may have gauged that I was cash strapped – I had only five rupias left – advised me not to buy a ticket on the ferry, but to claim I had a pass instead. By the time I reached Betim, I was left with eight tangas (eight annas) to pay for my bus ride to Mapuça. As I alighted, a European in a dinner jacket took leave of those seated beside him, and wished me boa noite (good night), as was Portuguese etiquette. I hailed a Mercedes Benz taxi. The tariff was two rupias, but those were days of honesty and no haggling. When I reached Ucassaim, it was already 8 pm. I had to bang on the door to jolt my relatives from their uninterrupted routine. Aunt Vitalina opened the door to her greatest surprise, for no one had expected me to beat the blockade and reach home. There were shouts of “Johnnie ailo! (Johnnie’s arrived)” from the neighbouring family house whose door had opened at the sound of the taxi. Uncle Alcantara came rushing down the steps ecstatic, and Aunt Vitalina rushed in to fetch money for the taxi fare. The next morning, the Regedor of Ucassaim, Chintamani Gaitonde, registered my arrival at the district police headquarters, O Commissariado do Norte, in Mapuça. But because the Brazilian embassy in Delhi had not specified the permitted duration of my stay in Goa, I had to also visit the Quartel Geral (Police Headquarters) and Secretariat in Panjim. The latter affixed revenue stamps of appropriate value on my passport, and entered a notation on the same page. The stamps were countersigned by the Director of Civil Administration, Dr. José António Ismael Gracias. On my return to Poona on September 20, 1955, the Portuguese immigration officer at Polém put a saida or exit stamp on my passport. Walking through no-man’s land, I was back at the Indian immigration post in Majali where I saw roughly three times as many people, as on May 30. My money deposited at the Customs was gracefully refunded, and I boarded the bus for Karwar, where I arrived by sunset and checked into Hotel Rodrigues for the night. The next morning, I boarded the 8 am bus for Belgaum and at two police outposts, beginning at Karwar’s municipal fringe, we were asked to alight and details of our permits were registered. Permits and etiquette at Polém On April 3, 1958, India scrapped its permit system, but locals in Goa had to still produce the Documento para Viagem; those in the rest of India had to posses a Certificate of Identity. This was in addition to the visa, a bilingual document in Portuguese and English, issued by the Brazilian Embassy in Delhi or the Quartel General in Panjim.  Those entering Goa had to still go through immigration checks at Polém, where Indian travellers without a health certificate issued by the municipality were administered anti-cholera and small pox shots; and travellers could exchange upto 50 Indian rupees for 50 Portuguese rupias. The Portuguese post in Polém was far more relaxed than the Indian one in Majali. In May 1960, my travel companion, an IAF Wing Commander who hailed from Porvorim, was invited to the Portuguese military-police canteen in Polém before he could board the bus to Margão. There was a standing protocol of courtesy when an Indian military man entered Goa at Polém. On another occasion, a woman who had lost her baby in Goa while on a visit, was graciously offered condolences by Portuguese immigration officials, on seeing the child’s death certificate. But when the same certificate was handed over to Indian immigration officials at Majali, they were sceptical and put the mother through some difficult questioning. Border blacklist Immigration staff at Majali had a thick handwritten book, with names of those considered personae non gratae on the basis of their activities in India, published writings, official placements in the Government of Portuguese India or connections with those on the same list. In Bombay, one never did know who was an informer, and even at a house party it was a safe bet never to air political views. I once stood behind an Indian immigration official as he checked my name against the blacklist, and found an equal number of Hindus and Catholics with remarks against their names. In January 1959, a family physician from Colaba, Dr. P.N. de Quadros and his family were debarred from entering India despite valid travel documents, and had to take a devious jungle route by country-craft to Bombay. Dr Quadros’ brother had been the President of the Military Tribunal in Goa, and had sentenced political agitators and satyagrahis. The same June, a pharma employee, Luis Antonio Chicó, and his family were detained in Goa for a month despite valid travel documents, and were allowed to return to Bombay only on the intervention of influential voices in Delhi. A few months later, a group of Goan tiatrists led by A.R. Souza Ferrão, and Fr Nelson Mascarenhas, assistant parish priest of St Francis Xavier’s Church in Dabul, were also disallowed entry to Majali for a month on their way back from Goa. It may surprise young readers to know that Goa had a small airline called Transportes Aéreos da Índia Portuguesa. It originated in 1954, after the establishment of airports in Goa, Damão and Diu, and flew tri-weekly. The Heron aircraft had to be navigated with skill to avoid violating Indian airspace. After the Indian land permit had been made partially redundant on April 3, 1958, several Goans took the train to Damaun Road (renamed Vapi) and tonga to Chaala on the Damão border, to catch a flight to Goa. Some broke the journey at the Parsi-owned Hotel Britona in Damão Pequeno (Little Daman). Last flight On October 7, 1961, the Government of Portuguese India issued the following press note: “The Government of the State of India came to know through the press of the Indian Union about the decision taken by the Government to open two more points of passage from her frontier to Goa via Banda and Anmode. The new points of passage across the frontier opened by the Indian authorities will contribute to facilitate travel of Goans to and from the Indian Union. For this reason the decision has been welcomed by the Government of this State and orders have already been issued for carrying out the work necessary to open as soon as possible the frontier of Partadeu via Pernem....”

cj3b.

The new routes

to Goa were never to be. They turned out to be Delhi’s carefully crafted

ploy to allow the Indian Army access to Goa’s heartland. On November

25, 1961, hostile vessels appeared off the Portuguese island of Angediva

and an Indian fisherman was shot while trying to fend them off.

Goa, 1954 The city of Goa and the surrounding area on the west coast of India had been a Portuguese ..

www.historytoday.com

Damaged

Portuguese military vehicles line the route to Panjim Airport, Goa,

December 19th, One of the problems vexing the Indian prime minister

Jawarhalal .

A few days later, Indian naval ships appeared at the entrance of the Mormugão harbour, and started to monitor shipping movements. Within a week, Indian soldiers and armoured vehicles were parked at the frontier. Placido Rodrigues, a Goan traveller who happened to be at the Majali post on Sunday, December 17, 1961, was whisked away to safety by the Indian military, as armoured columns topped up fuel tanks and cranked their engines en route to Polém. At 4 am the next day, the Indian army entered Goa, ending 451 years of Portuguese rule  . .  Vasco_Da_gama_POW_camp.jpg Vasco_Da_gama_POW_camp.jpgThe Indian Chief of Army Staff, Gen. Pran Thapar (far right) with deposed Governor General of Portuguese India Manuel António Vassalo e Silva (seated centre) at a POW facility in Vasco Da Gama, Goa happy people of Goa with Indian national flag after liberation from portugal  John Menezes retired as the Chief Mechanical Engineer of the Bombay Port Trust. He lives in the heart of old Bombay, researching and writing about a city that jogs only in memory. This is an extract from Bomoicar: Stories of Bombay Goans, 1920-1980, edited and compiled by Reena Martins, Goa,1556. Available via mail-order from goa1556@gmail.com.  on google images type :-'DECK PASSENGERS SLEEPING ARRANGEMENTS' you will get the old photos of traveling in ship |

The

Konkan Shakti, one of two passenger steamers operated by Chowgule-owned

Mogul Line - See more at:

http://www.mid-day.com/articles/stories-of-mumbais-goans/15360197#sthash.lWE8s68S.dpuf